In North Memphis, milk crates and cardboard boxes sit under a pecan tree that doesn’t bear fruit anymore. Kathy Yancey-Temple is building raised beds for a community garden on her street. On a sunny autumn morning she spends her time buying soil to fill these upcycled planters. She doesn’t trust what’s in the ground.

“It’s years and years of pollution. We just make the assumption, because why wouldn’t it be contaminated?” says Yancey-Temple, a smokestack behind her. She lives in Douglass Park, an island amid industrial manufacturing plants. Some call it Memphis’ chemical corridor.

“We are surrounded by industry. Not only have they victimized us by putting these large industries across the street, but companies like Velsicol have not properly cleaned up.”

Within walking distance of her home, Velsicol manufactured chemicals for pesticides so powerful that a spray could kill a flying insect before it even hit the dirt. Velsicol was a large producer of products like chlordane – a man-made substance that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) banned in 1988 because of its cancer risk. Velsicol’s North Memphis legacy is still alive in the depths of the Wolf River and shallow layers above the Memphis Sands Aquifer, where sediment contains hazardous industrial chemicals that do not dissolve in water.

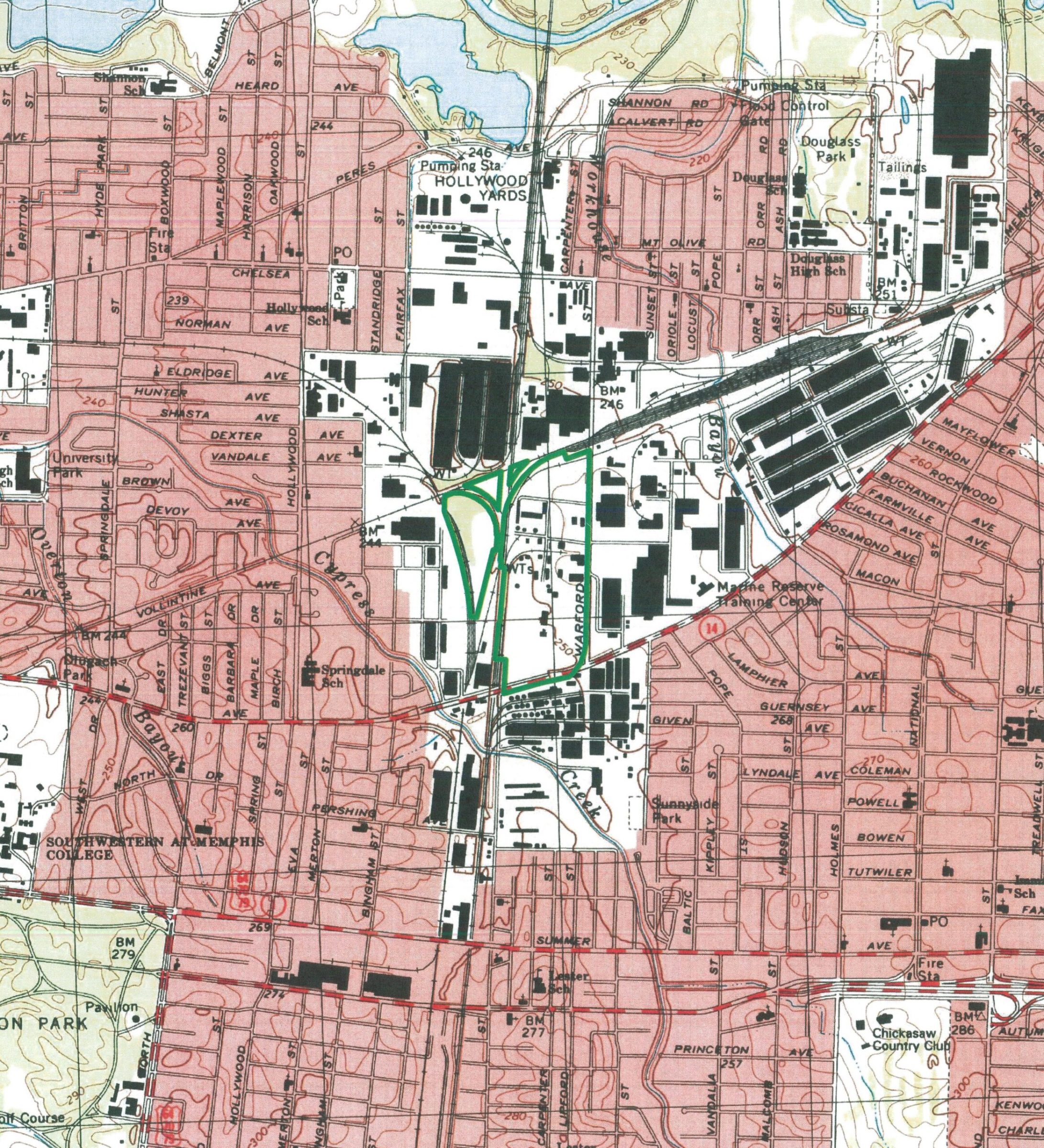

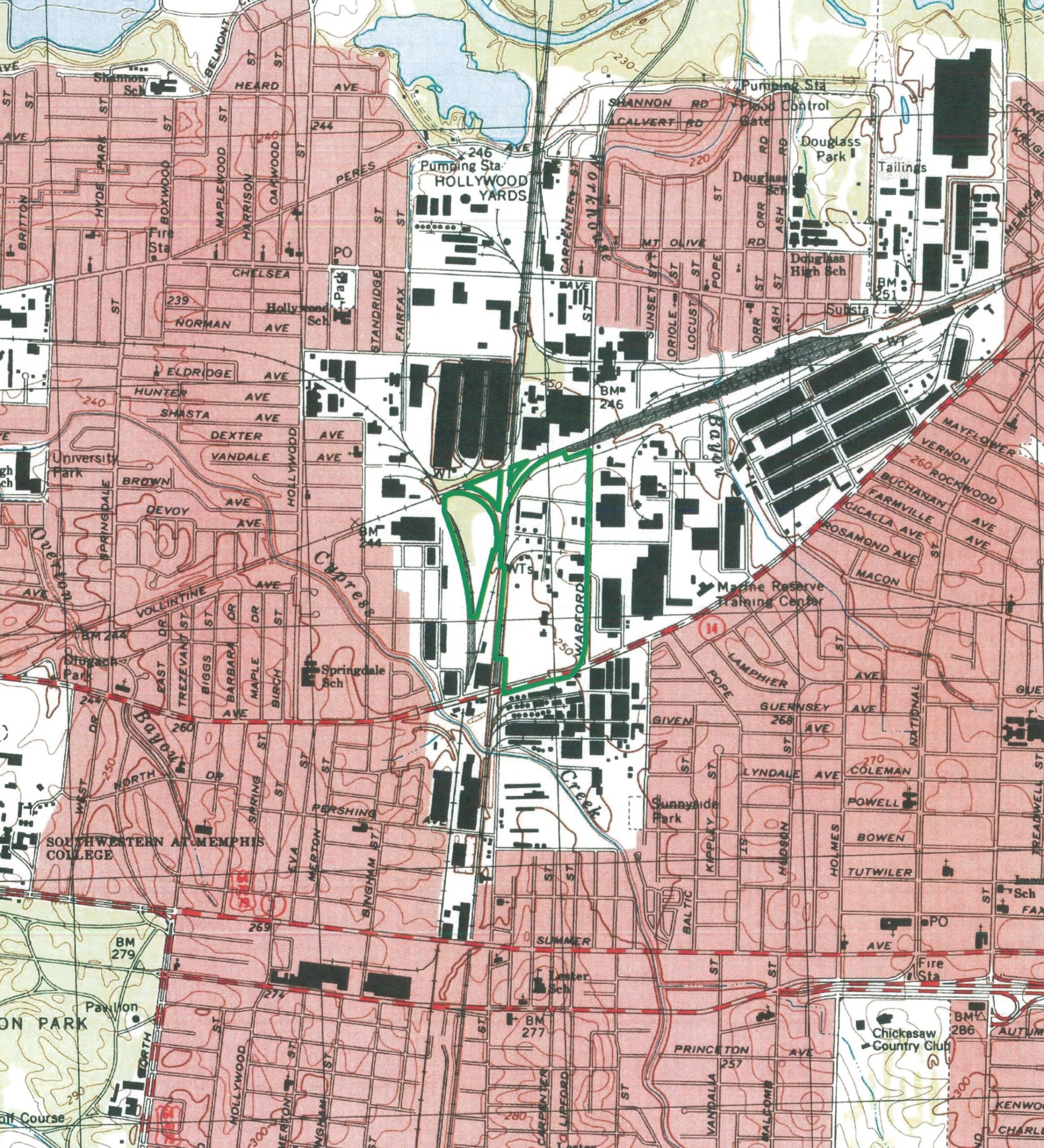

While Velsicol facilities across the United States have become Superfund sites — a federal designation that allows the EPA to fund clean-up of contaminated sites — their Memphis location, 1199 Warford St., has been operating under a state-sanctioned permit that allows Velsicol to store, treat and dispose of hazardous waste.

Velsicol’s Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) permit expires in two years. Community members and environmental activists are asking that state agencies, elected officials and the EPA carefully review what’s been done in the last decade. Investigations in other cities, like a lawsuit filed in Washington, D.C. this October against Velsicol, found the company financially responsible not just for environmental degradation at one of their facilities but for the cost of cleaning up citywide rivers, with traces of chlordane.

We are surrounded by industry. Not only have they victimized us by putting these large industries across the street, but companies like Velsicol have not properly cleaned up.

– Kathy Yancey-Temple, resident of Memphis’ Douglass Park neighborhood

Velsicol has not publicly responded to that lawsuit, and their vice president who oversees the Memphis facilities did not want to comment on national or local future plans.

For Yancey-Temple, getting honest answers from neighboring industries is part of addressing the injustice that goes back six generations. The Rev. W.A. Plummer, formerly enslaved, founded Douglass Park for other Black families to safely buy property during Reconstruction. Her family has been there ever since.

A heritage of being close to the soil influenced the community from its inception, according to the Memphis Landmarks Commission. In this bayou, people grew their own food and caught fish for decades. Meanwhile, industries tucked them into a corner between highways and railroads.

Everything goes belly up

Velsicol earned its foothold in the mid-century industrial economy with chemicals that killed living things – insects, rodents, plants – cheaply and efficiently.

Old manufacturing sites like their 1942 Memphis facility dot the country. State, local and federal regulators are still negotiating cleanup at long-shuttered plants in places like rural Illinois, where chlordane was also made, and a suburban New Jersey site that processed mercury. Cleanup at a former Velsicol site in central Michigan, where the company produced DDT and the flame retardant polybrominated biphenyl, has been stop-and-start for 40 years. These properties occasionally change hands, laden with millions of dollars of liability and flirting with bankruptcy.

Additionally, landfills in the southwest corner of Tennessee where Velsicol sought to dispose of their chemicals made Superfund Site status: one in the Hollywood community in Memphis and the other in Toone, an hour east of Memphis. In Toone, Velsicol buried over 300,000 55-gallon drums of industrial waste that contaminated nearby water and soil. Neighbors sued, initiating Sterling vs. Velsicol, an 8-year legal battle in which Velsicol was held liable for millions in damages. The ruling was overturned on appeal.

The company’s slow collapse started with the scrutiny that followed Rachel Carson’s American reckoning with the chemical industry through her 1962 book “Silent Spring,” credited with the start of the modern environmental movement. It warned about the long-term effects of DDT and its wider family tree of industrial chemicals like chlordane, dieldrin and endrin. All were made in Memphis.

Carson’s words wielded such power that Velsicol threatened legal action against her publisher. The book started to unravel Velsicol’s biggest value proposition: manufacturing highly profitable chemicals that posed threats to the health of people and their environment.

As national pesticide policy evolved, two U.S. senators pointed to Velsicol’s waste-treatment plant in Memphis as the source of neurotoxic endrin in the lower Mississippi River where millions of fish floated, belly-up. Cypress Creek — which feeds the Wolf River and, eventually, the Mississippi — abuts the Velsicol site. A Carson biographer, Linda Leer, reported that the senators used this as final evidence to draft a predecessor to the Clean Water Act.

In the next 30 years, the EPA heavily regulated the use of chlorinated pesticides. During that time, Velsicol and its assets were bought and sold for parts.

However, they did not regulate the manufacturing and export of chlorinated pesticides for other countries. Through the early 1990s, Velsicol’s plant in Memphis became the sole U.S. producer of chlordane, favored for killing termites, according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. A United Nations treaty in 2001, signed by 90 countries, banned what they called the dirty dozen, a spate of pesticides including chlordane. Velsicol was eventually acquired by private equity firm Arsenal Partners for $250 million in 2005. It closed its Memphis plant in 2012.

Technically, Velsicol continues to operate the 62-acre site, still leasing out space while it cleans up its legacy pollutants – a description used by governments to describe banned chemicals that linger in the environment. But understanding Velsicol’s remediation can be like trying to see through the Mississippi River.

The Lookout filed public records requests with five state departments to learn what Velsicol has cleaned up since shutting down its plant. The Tennessee Department of the Environment and Conservation released 125 public records that document 40 years of Velsicol cleanup.

Under RCRA, Velsicol is required to submit a yearly Corrective Action Effectiveness Reports (CAER). To accurately understand the technical data in these reports, the Lookout talked to lawyers, policy analysts, and chemists who work with site remediation.

The latest CAER, submitted this year, shows that, over the last decade, Velsicol has been remediating contaminated groundwater and a contamination plume emanating from its site. The underground cloud where contaminants have slowly seeped through the soil is roughly the size of Liberty Bowl stadium: 126 acres. About 60 percent of the plume reaches into what Velsicol calls a “deep zone.”

Velsicol monitors a network of wells to calculate the boundary and weight of the plume, made mostly of carbon tetrachloride – a chemical used as house cleaner that is now also banned for consumer use by the EPA.

The wells are estimated to annually remove 2,229 pounds of carbon tetrachloride. Based on Velsicol’s annual reports to TDEC over the last decade, their system of pumping out water to treat it for pollutants is working. Their plume has decreased from over 80,000 pounds to 7,000 pounds of carbon tetrachloride. Velsicol reports the plume is “under control.” According to members of the American Chemical Society, that doesn’t mean that what remains isn’t a concern.

“The fact that they have removed 90 percent doesn’t mean that it’s 90 percent less toxic. There’s much more in terms of threat and potential injury than just the total,” said Christopher Reddy, a marine chemist who analyzes drinking water for pollutants, including pesticides. “Pollution and chemicals, it’s a lot like buying a house, it’s all about location. Where is that 7,000 right now and how does that impact the local neighborhood?”

The plume doesn’t stay in just one place beneath 1199 Warford. It moves. In 2018, it spiked to 280 acres – its original size – before shrinking to its current acreage. TDEC attributes the fluctuation to heavy rainfall. Executive Director of Protect Our Aquifer (POA) Sarah Houston said future rain events like this are likely to continue moving the concentration of chemicals downward.

POA is a watchdog organization that tracks contaminated hotspots throughout the aquifer — a subterranean reservoir of saturated sands that is the region’s drinking water source for more than a million people. Polluted sediments can contaminate water as it seeps down into the natural reservoir.

“The flow of groundwater is just so slow in Memphis, and that has been one of our saving graces as far as all these polluted sites,” Houston said. “Most haven’t reached our drinking water yet, even though they’ve been in the ground for, you know, 50 to 80 years. So, when you see those kinds of spikes in concentration, in the deeper formation, it means that it’s had enough travel time to get that deep. We have these ticking time bombs all over Shelby County.”

Meanwhile, above ground, chemicals like chlordane and dieldrin have attached themselves to upper layers of soil. Guided by RCRA regulations, the remediation for topical contamination has been a slow march of inspections, investigations, action plans, status reports, and investigations.

As recently as 2018, soil samples for dieldrin were under the limit for commercial properties, but nearly three times the EPA standard for residential properties, like at the nearby Springdale Apartments.

The fact that they have removed 90 percent doesn’t mean that it’s 90 percent less toxic. There’s much more in terms of threat and potential injury than just the total.

– Christopher Reddy, a marine biologist who analyzes drinking water for pollutants

Velsicol extracts contaminated soil, puts it in a dump truck, and moves it to a baseball diamond-shaped consolidation pile at the northwest corner of its property by railroads, according to TDEC Deputy Communications Director Kim Schofinski. Each time soil is added to the pile, a tarp-like impermeable liner is put over it and welded into place. Eventually, the pile will be capped and “monitored in perpetuity to ensure the cap is not compromised,” Schofinski wrote in an email.

The Lookout filed a public records request to find out how much Velsicol has spent over the last 10 years, but the department of revenue denied the request citing sealed records. As part of Velsicol’s legal requirements for their RCRA permit, the company had to assure the state they could provide enough money to cover the cost of cleanup. They proved they could commit to $2.5 million.

Velsicol’s RCRA permit will expire on Sept. 30, 2024. They must submit their application 180 days before the expiration date. Velsicol will be legally required to release a draft permit and host public participation for feedback on their plans. It’s a process communities across Tennessee are long familiar with.

Pushing for answers of today

As Velsicol closed the doors to its Memphis plant 10 years ago, another community across the state grappled with its own defunct site. In Chattanooga, the Velsicol plant produced its own toxic set of chemicals like benzene, chloride, and benzoic acid in Alton Park — a Black community with industry sprawled around them and a similar history to Douglass Park.

The Sierra Club, Chattanooga for Action, and other environmental groups were organizing against TDEC and Velsicol, because they believed solutions proposed under an emerging hazardous waste permit were insufficient.

Attorneys writing on the behalf of the conservation group Tennessee Riverkeeper sent TDEC a letter saying the agency was “just rubber-stamping an inadequate remediation plan submitted by Velsicol.” The attorneys in that letter went on to express concerns about the environmental sustainability of the plan and argued that by just covering up contamination, hazardous liquids would continue to drive deeper into their limestone aquifer.

“We have ‘residue hill,’ where there were chemicals buried out there on site, and so if we have a tornado, an earthquake, or something like that, it can disturb the chemicals,” said Milton Jackson, who served as president for a group called Stop Toxic Pollution (STOP). “I don’t care how much dirt you put on top of the property. You are still going to have underwater currents and chemicals in the ground.”

Jackson started investigating Velsicol and other industries in the early 1990s when his wife’s asthma worsened. He went to every level of government involved in overseeing environmental pollution to get information and then took his questions to Velsicol executives. His research was so extensive that he worked with the University of Tennessee to publish a case study on environmental justice and community collective action.

So when Velsicol went to modify their Chattanooga permit in 2011, Jackson and the environmental organizations were ready to hit the streets with petitions. It resulted in changes to the permit including a deeper soil cover and explicit language about soil establishing and maintaining vegetation.

“(Activists) can do the same thing in Memphis too, they can do the same thing as I did, but you have to stay with them and go in and talk with them,” said Jackson. “Get all the facts together, and they will do what you want.”

When given the opportunity, Memphis residents have also pushed back. In 2008, Velsicol settled a class-action suit in the Hollywood community that paid out $2.1 million to the owners of 195 nearby properties contaminated by dieldrin.

They’ve also spoken up during previous permit renewals. Records from TDEC provide snapshots of neighbors’ responses to Velsicol cleanup at 1199 Warford. Residents have long held the suspicion that Velsicol’s process lacks clarity, tainted by asymmetric information meant to favor the company and leave residents in the dark. Questions at a 2006 community meeting at the Hollywood Community Center mirror the public’s concerns today: What is tested, who sees those results and who decides what happens next? Who pays for it? Is it safe for us to grow vegetables in our backyards?

The problem now is that residents and environmental activists are having a hard time meaningfully connecting with Velsicol, raising more questions about who still works for Velsicol and what they spend their time doing.

According to monitoring reports filed over the last decade, Velsicol employs at least one person at its Memphis facility. As of 2018, site manager Dawei Li oversaw the storage and disposal of hazardous materials. Hazardous waste inspection reports show that Li, along with Vice President George Harvell, participated in state-led compliance evaluations and corrected minimal violations such as mislabeling used oil.

The Tennessee Lookout emailed Li and Harvell, requesting interviews. After no response, a reporter went to the Velsicol site to ask for an interview in person.

Empty vending machines stood outside a shipping-and-receiving building, where a man opened the door. He connected the reporter with Li. Harvell was also there and said Velsicol is still trying to remediate and redevelop the property — the similar vague statement Velsicol made nearly eight years ago when its RCRA permit was approved. In the interim, they’ve been trying to lease space on the site.

Harvell said his company’s ethics have changed; they are dedicated to managing the contaminants and plan to renew their RCRA permit.

“The Velsicol of today is different than the Velsicol of yesterday,” he said.

Harvell said his company has been transparent throughout the RCRA permit. The next day, he withdrew his commitment to a full interview with the Lookout.

The healing of a river and its people

Beneath the amber-colored water and knobby roots of swamp-thriving conifers, the bass, catfish, and perch dwell in the Wolf River’s contaminated sediment. As they swim, their bodies pick up carcinogens.

Chlordane is among the most frequently found containment at dangerous levels in fish, according to TDEC sampling. It accumulates in their fatty tissue, posing a risk for people who eat them. While visible TDEC signs warn of the effects, people still go to the river to catch fish for a meal.

Ryan Hall – director of Land Conservation at the Wolf River Conservancy – stands on a sandbar in the river behind Douglass Park. Near him, a monarch butterfly lands on a discarded tire.

It’s only the final 22 miles of the Wolf River that runs through Memphis from the mouth of the Mississippi that has endured a host of toxic chemicals. Upstream, at the iconic Ghost River section of the Wolf, it’s an ecologically intact, natural wonder.

Velsicol’s RCRA permit does not cover clean-up at the Wolf River, but Hall’s organization is devoted to protecting these wetlands – once so ruined by pollutants that biologists called it a dead river.

“Water quality is at the mercy of our soils,” says Hall. “What was dumped into it is one of the biggest degradation factors of the Wolf River ecosystem.”

The Wolf River has been making a comeback through natural ecology and time. It’s a kind of healing that people like Yancy-Temple and her community are experiencing themselves.

Yancey-Temple doesn’t only spend her time in the garden. She is a community advocate for the Center for Transforming Communities, a group trying to create sustainability in economically depressed areas.

She says they can’t separate poverty from pollution, that the exploitation of Black people, land, and water are interlinked. It’s a systemic issue discussed widely between scholars and movement leaders in environmental justice.

“We’re trying to get back to what was already natural here,” says Yancey-Temple. “We’re just at the beginning of it.”

Tennessee Lookout is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Tennessee Lookout maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Holly McCall for questions: info@tennesseelookout.com. Follow Tennessee Lookout on Facebook and Twitter.