More people left Memphis over the last two years than any other part of the state. That’s a bad sign for the area’s economic growth, according to a Tennessee labor expert.

Marianne Wanamaker, a labor economist at the University of Tennessee, told state lawmakers Tuesday that — from an output perspective — the U.S. and Tennessee economies are “operating as though Covid never happened.” However, fewer people are working, and 95,000 employees are needed for jobs in Tennessee. Now, there’s only half that number of workers available in the state.

Bridging the gap between high output and fewer workers means those who are working spend more time at their jobs. Wanamaker said this may explain “why working Americans express feeling burned out and exhausted.”

The American labor supply “took a beating” during Covid, Wanamaker said, and is struggling to recover. She said it’s unlikely that the labor force participation rate (the amount of Americans working or actively looking for jobs) will ever return to the record 67-percent rate experienced in the late 1990s before the dotcom bubble.

More than 2.1 million Americans retired early in the pandemic, Wanamaker said. Unlike previous times, she does not believe many of those will “un-retire” and return to the workforce, wiping out a significant portion of the “bonus labor force.”

Many blamed the so-called worker shortage on emergency pandemic unemployment insurance benefits from the federal government. So sure of this notion, Tennessee Republican lawmakers opted the state out of said benefits to prod those taking the money back into the workforce. Wanamaker said “our draw down on unemployment insurance is quite low compared to where we were last year.”

Sen. Frank Nicely (R-Strawberry Plains) said many “snowflake millennials” are now just living off the wealth of their dying parents.

“I was reading the other day that us war babies and Baby Boomers are dying off and there’s been a huge transfer of wealth to snowflake millennials — one of the biggest transfers of wealth in history — and a lot of them don’t have to work,” Nicely said. “They inherited a house and they got money in the bank. A lot of them are in pretty good shape. What impact does that have on people not working?”

In response, Wanamaker said, without unemployment insurance, people are financing non-work in other ways. She said the labor market is experiencing weakness at all education levels, but remarked vaguely on the recent increases in the stock market and housing valuations in Knoxville.

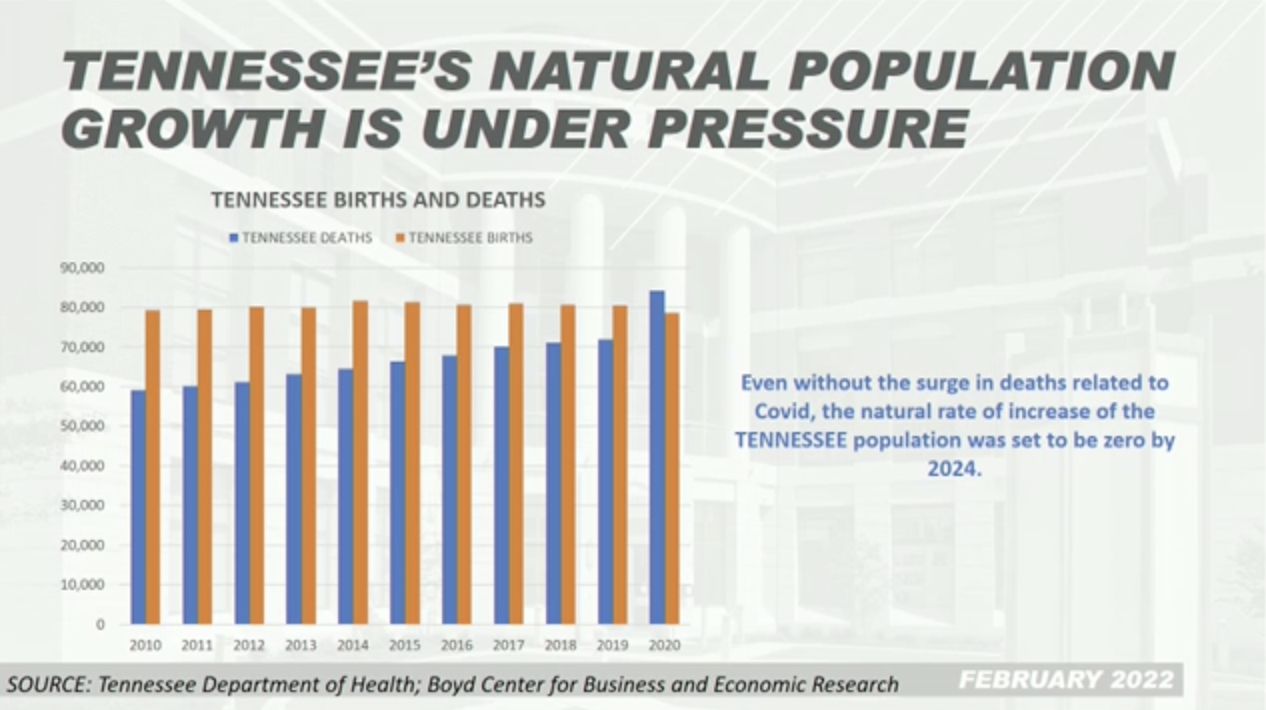

Wanamaker focused on the fact that an economy cannot grow without people, and that’s a challenge for Tennessee at the moment. Deaths exceeded births in the state by 7 percent in 2020, she said. Even without Covid deaths, Wanamaker predicted that deaths would have exceeded births here by 2024.

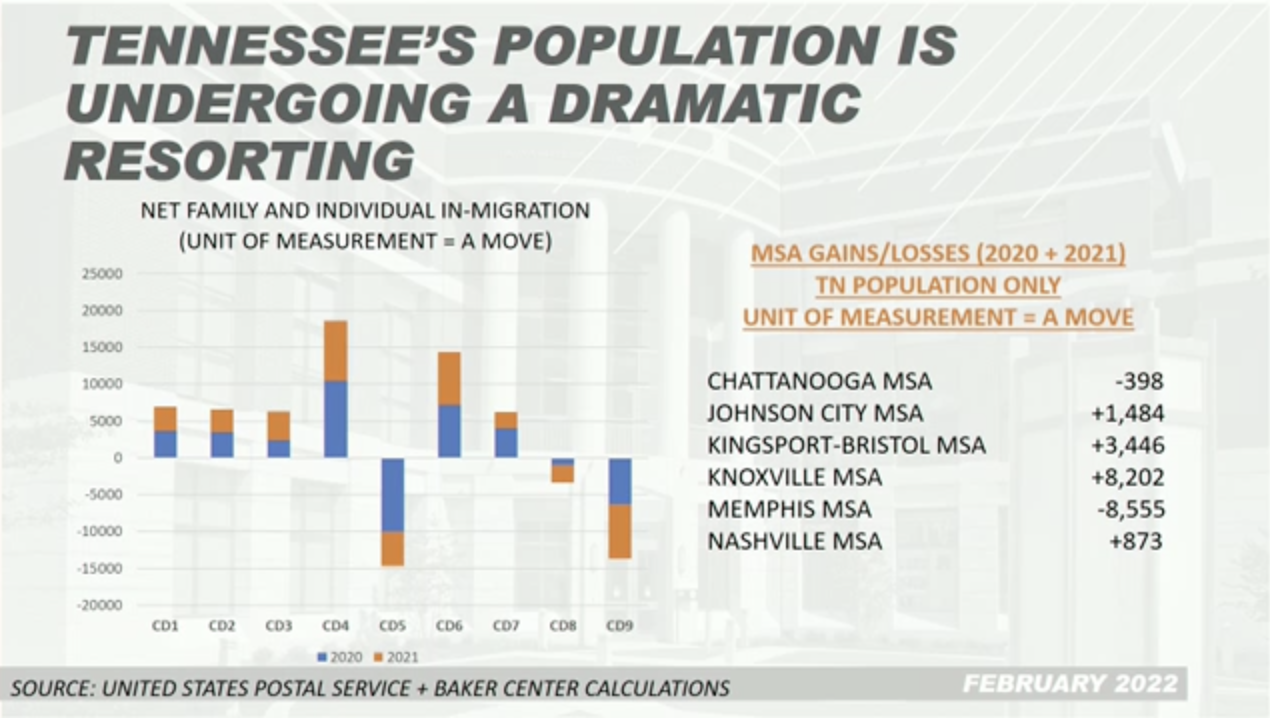

The only population growth for the state that year came from people arriving from other states. Without that, she said, Tennessee’s population would be shrinking and dragging economic growth. Those migrations did not happen uniformly across the state. In fact, Memphis was — far and away — the biggest loser.

To track migration, Wanamaker used U.S. Postal Service data from change-of-address cards. Someone moving gives the Post Office the address they’re moving from and the address they’re moving to. Each change of address card is considered one household, and each household is conservatively considered to be about two people. From this information, migration trends can be calculated.

Knoxville, the state’s biggest population winner, gained 8,202 households (or 16,404 people) in 2020 and 2021. Bristol gained 3,446 households (or 6,892 people), while Johnson City gained 1,484 households (or 2,968 people).

At the same time, Memphis lost 8,555 households (or 17,110 people), in those two years, losing “as many households as Knoxville has gained,” Wanamaker said. U.S. Census Bureau data show that Shelby County’s population rose by only 2,100 people between 2010 and 2020 (from 927,644 to 929,744), or 0.2 percent.

“I believe population and labor force dynamics are the major policy challenges of the next 5 to 10 years,” Wanamaker said. “Supply chain snarls will abate. … It remains very possible that the [Federal Reserve Bank] will find a soft landing on inflation that will keep us out of a double-dip recession.

“Meanwhile, the labor shortage and lack of population growth is going to be a challenge with 100-percent certainty.”

As for a remedy, Wanamaker said “recruiting migrants [from other states and legal immigrants form other countries] to the state will determine the rate of economic growth over the short and medium term.”