With suburban sprawl derailed by energy costs and subprimes and downtown sleeping off the condo hangover and arena fatigue, attention has shifted to some potentially big deals in Midtown.

One of them, proposed by Memphis developer Henry Turley, would redevelop the Mid-South Fairgrounds as a sports complex, Kroc Center, hotel, and shopping center. A second proposal by Miami-based WSG Development Company would put a 28-acre retail center in a blighted area near the intersection of Poplar and Cleveland. Both projects would cost several million dollars in public and private investment, rely on complicated tax schemes to attract national retailers such as Target or Wal-Mart, and won’t show tangible results for at least another year.

Big-store fever has also spread to downtrodden Overton Square, where there is some buzz but no firm proposal about a new grocery store and hotel.

That something needs to be done is obvious. Over half of the fairgrounds property is vacant, and someone driving on Cleveland from the abandoned Sears Building to Methodist Hospital on Union Avenue would think Midtowners mainly shop for auto parts and title loans. The question is what? Midtowners are a diverse, activist, and choosy bunch — fiercely loyal to what they like and fiercely critical of what they don’t like. And downtown’s Peabody Place is a reminder that multi-million-dollar mixed-use retail projects with the best planners that money can buy can fail.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

If any of this works, the developers will owe a debt to small businesses and neighborhoods that invested in Midtown without fanfare or tax benefits, relying on personal risk, sweat equity, customer loyalty, and creativity. They range in size from the residential redevelopment of the abandoned Interstate 40 expressway corridor to restaurants and small businesses in Cooper-Young and the Evergreen Historic District.

Big or small, successful projects filled an unmet need — new houses with historic architecture, a walking trail on an abandoned railroad line, a Home Depot in a building that had failed twice as a grocery store, a movie theater in Overton Square that outlived a much bigger competitor downtown, or a family-run neighborhood restaurant whose owner trained at Bennigan’s, the bankrupt national chain. They succeeded because people wanted them and liked them. They got little or no assistance from tax credits or quasi-government agencies like downtown’s Center City Commission. There were no debates about development fees or corporate logos. Collectively, they help make Midtown the unique group of neighborhoods that it is.

First, a little disclosure. I have beaten this horse before. Fifteen years ago I coined the slogan “Midtown Is Memphis.” The driving force was driving. Some Midtown parents were tired of hauling our children to Cordova and Germantown for shopping, movies, and sports, especially when two Midtown teams would play each other. Artist Tom Foster and I put the slogan on a bumper sticker that is still around, no thanks to me. Our design was full of graphic icons of happy little scenes. Midtowner Calvin Turley reduced it to its current white-on-red or green-on-white incarnations. Less was more. His son Rayner and daughter Lyda sold a ton of them.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

The campaign fizzled. The school board and Park Commission collaborated on a track, two baseball diamonds, and an alleged soccer field next to East High School, the sum of which is a sportsplex in name only. So the bumper sticker was overdesigned, and the sportsplex was underdesigned. There is probably a lesson in there somewhere.

Anyway, here are some Midtown projects with real staying power and comments from some of the people who got it right and made it work.

The Overton Park Expressway Corridor: A generation has grown up since Midtown just west of Overton Park was marked by a swath of weeds, vacant land, and broken foundations 400 yards wide and nearly a mile long. Even residents have a hard time telling where the old houses end and the new ones begin on some blocks. From 1992 until about 2003, more than 200 new bungalows and four-squares were built to historic guidelines on land bulldozed for an expressway 30 years earlier. (More recently, another Midtown residential infill project followed similar guidelines after the old main library was demolished at Peabody and McLean.)

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Neighborhood leaders obtained historic designation for the Evergreen Historic District. The city reacquired the land and sold lots through real estate agents to former owners, builders, and prospective homebuyers. Construction quality was uneven, but architectural guidelines were enforced, and within a decade most empty lots were gone.

“Three things were done well,” says Dexter Muller, former director of the city’s division of Planning and Development. “The first was working through issues of ownership and acquiring the land. At the state and federal level that was a challenge, and I really give credit to my assistant, Cindy Buchanan [currently director of Parks and Recreation]. The second thing was a plan that was realistic in the marketplace. There was so much demand you didn’t need government incentives. And third, the planners and local government set it up as a historic district and imposed guidelines to make it compatible with what was there. That was huge.”

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

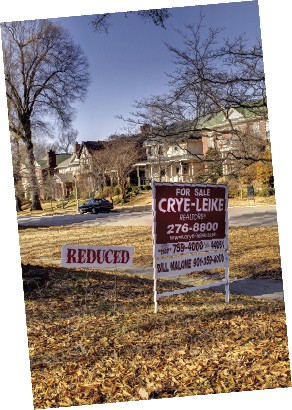

Corridor homeowners, like Shelby County commissioner Deidre Malone and her husband, made the planners look good. The Malones bought their lot in 1993, hired an architect, moved into the house in 1994, and have been there ever since.

“We went through the Landmarks Commission process and everything,” said Malone, who was working in Midtown at WMC-TV at the time. “They wouldn’t let me have shutters on the house. But I moved on. Our kids went to Snowden and Central, which are great neighborhood schools. We love the feel of Midtown. It’s a very diverse community, and the neighborhood association is fabulous.”

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Malco’s Studio on the Square: Opened in 2000, Malco’s boutique four-screen theater has been an unqualified success while Muvico’s Peabody Place megaplex, which was built at about the same time, has closed. The theater was developed by Memphis-bases Southland Capital, which planned to redevelop all of Overton Square but has sold its interest. The section south of Madison is still struggling, with several vacancies but a tantalizingly large parking lot that keeps the rumor mill grinding.

“I’m a Midtown proponent and convinced our people it would be a wise thing to do,” says Malco’s James Tashie. “Parking is critical for us. We wanted this theater to be bigger with more screens but parking prohibited it. Still, we’ve held our own very well with the big guns downtown.”

Tashie said the developers got some tax credits “but that didn’t tip the scales for us.” The original concept of an “art house” was discarded for more standard fare, but the theater is still very different from, say, Malco’s Paradiso in East Memphis.

“Our theater fit the niche of Midtown. We do a lot of film festivals and special events there, and we have a sitting area and a wine bar. I think it works for that reason. But if you don’t have movies people want to see, it doesn’t matter what you build.”

The V&E Greenline: An abandoned railroad line in the middle of a stable neighborhood was a challenge for the Vollentine-Evergreen community. Rhodes College professor Michael Kirby was one of the neighbors who bought the land in 1996 and turned a potential trouble spot into a walking and biking trail.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

The 1.7-mile Greenline is much shorter than a proposed railroad abandonment bike trail to Shelby Farms, making acquisition costs and construction much cheaper. Organizers got less than $10,000 from government sources to build a bridge and a storage building and develop a master plan. They raised many times that amount in donations from Keeler Iron Works and other businesses and in donated labor for the original clean-up and ongoing maintenance.

“We used to think the area between University and McLean was unsafe,” said Kirby. “People had a vision of a trail that was nicer than what we had, and the more it was improved, the more people started using it. I remember seeing a 75-year-old lady in the neighborhood walking her dog, and the fact that she felt safe enough was an indication of our success.”

Stewart Brothers Hardware: Stewart Brothers, at Madison and Cleveland, is the ultimate Midtown survivor, founded in Memphis in 1887 and occupying the same location since 1935. Like a sprawling old house, it has expanded several times as space became available, but it’s the antithesis of the big-box store. A sled, a child’s bike, tools, and the $1 bin are all on display a few steps from the cash register and entrance.

“Our specialty is customer service,” says Chris Dempsey, 36, one of five family members working in the store purchased by his father, Jim Dempsey, in 1975. “We’re able to greet customers when they come in the door, take them to the product they want, and answer any questions.”

Stewart Brothers has never received any tax breaks, unless you consider being next to MATA’s $60 million Madison Avenue trolley extension a break. Dempsey doesn’t. Construction was “a terribly negative process” that cut business 35 percent. He knows of no benefits and says “the road back up was a lot harder than the fall.” He would welcome the proposed development at Poplar and Cleveland and the demolition of blighted properties.

Fresh Slices Sidewalk Café & Deli: If you’re not looking for Fresh Slices and its neighbor, Diane’s Art Gift and Home Store, you won’t find them. Midtowner Diane Laurenzi, a respiratory therapist at the time, opened her store in a former Masonic Lodge in the middle of the Evergreen Historic District in 2002. The restaurant opened in 2004 and an upstairs gallery this year. They get no tax credits.

Fresh Slices owner Ike Logan had several years experience with the Bennigan’s restaurant organization. Eight family members work in the restaurant, which emphasizes neighborhood ties with dishes named after residents.

Laurenzi features neighborhood artists in her gallery and store, which became profitable after two years. She makes it a point to make friends with her customers and carry a variety of items at different price points.

“The neighborhood is very loyal to our business, and part of that is we have something to offer them,” she says. “I think they want to see us do well.”

The Levitt Shell in Overton Park: “Save Our Shell” was a rallying cry for decades, but the outdoor bandstand and shell appeared to be doomed until the Mortimer Levitt Foundation came to the rescue thanks to a chance encounter.

Memphis musician David Troy Francis was performing at a restored shell in Pasadena, California, and had dinner with Elizabeth Levitt Hirsch. He told her she had to come to Memphis.

“We had lunch at the Brushmark and then walked over to the shell,” said Barry Lichterman, president of the shell’s board of trustees. “She looked at it and said, ‘This is it. I want to do this in Memphis.'”

The Levitt Foundation donated $250,000 for renovation and $500,000 for operating costs for the first five years. The city of Memphis contributed $500,000, and an additional $600,000 was raised from private sources.

Lichterman credits the shell’s initial success to architect Lee Askew, who lives nearby, and to local donors. The Levitt donation is only a start. It costs $450,000 a year to operate the shell, so “without local participation this is not going to happen.”

Cooper-Young Business District: Midtown’s most successful neighborhood restaurant and entertainment center is 20 years old this year. It has overcome safety fears and a lack of parking garages with a police mini-precinct, an annual street festival, and constant marketing.

“This is a tribal gathering place, and the one element you have to have is safety,” says Charlie Ryan, a Cooper-Young investor and president of the Cooper-Young Business Association.

Ryan is proud of the district’s independent business owners and absence of franchises.

“That is the beauty of it,” he says. “Nowadays, you do a lifestyle center and talk to all the big boxes and wind up with something boring. Cooper-Young is not boring. It is unique.”

The district does not receive the sort of tax credits that are commonplace downtown and in the proposed fairgrounds and Poplar-Cleveland projects.

“We got a HUD grant in 1991 for $500,000 for street improvements, street trees, and antique lights, and some of the individual owners got historic credits for facades on their buildings,” Ryan says.

“We operate on the Karl Rove theory of commercial. The truth is what you say it is. Every few months we came up with something to get some publicity. The festival is a once-a-year public relations event that says it is okay to come to Cooper-Young, and we are a cool place. You don’t have to put in gazillions of dollars if you’ve got creative people. There is a lot to be said for just working with what you have and building on your strengths.”

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks