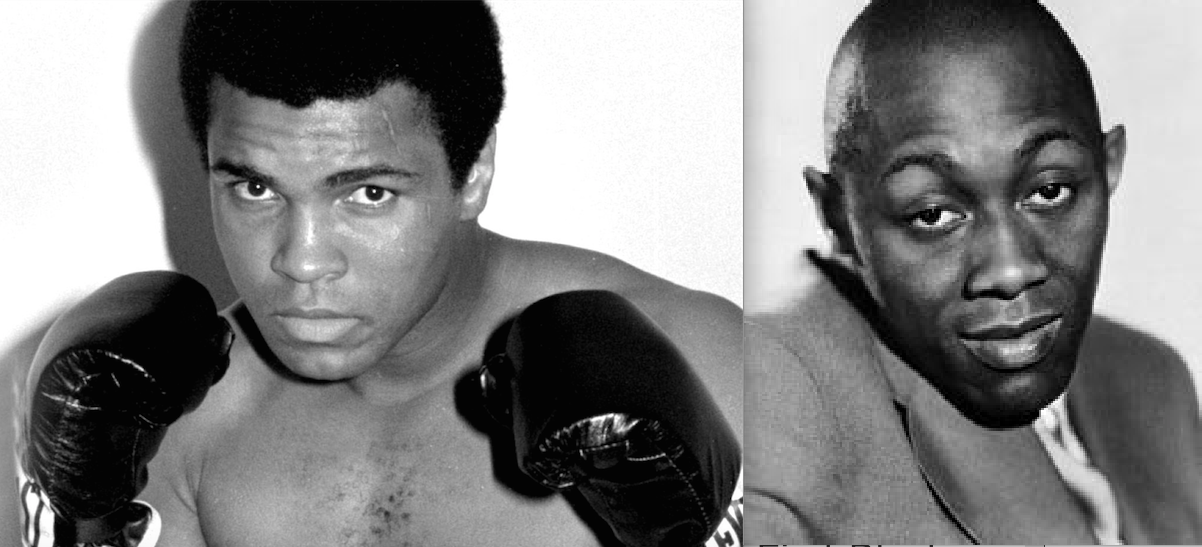

Muhammad Ali, Lincoln Perry AKA Stepin Fetchit

“The search for the white hope not having been successful, prejudices were being piled up against me, and certain unfair persons, piqued because I was champion, decided if they could not get me one way they would another.” — Jack Johnson

“I’m bold, he was crazy.” — Muhammad Ali on Jack Johnson.

“There’s power in the art of doing nothing.” — Stepin Fetchit

Will Power’s play Fetch Clay, Make Man, currently on stage at the Hattiloo Theatre, is set just after the assassination of Malcolm X, and just before Muhammad Ali’s rematch with Sonny Liston. It explores the strange alliance and unexpected bond that formed between Ali and the delegitimized comedian Stepin Fetchit, as the boxer sought to unlock the secrets of Jack Johnson’s “anchor punch.” It’s a conflict-laden meditation on identity, and what it means to be a black celebrity in America. Look for a full review of the show in days to come. In the meantime, here’s a quick look back at Fetch Clay Make Man‘s crucial trinity — Ali, Fetchit, and Johnson .

Muhammad Ali Meets Stepin Fetchit at The Hattiloo Theatre

It’s difficult imagining Stepin Fetchit, Hollywood’s first black millionaire — an embarrassment and “race traitor” in they eyes of following generations — as the bridge between the first black heavyweight champion, Jack Johnson, and the celebrated boxer and black power icon Muhammad Ali. But as Ali prepared to take on both Sonny Liston and U.S. military involvement in Vietnam, Fetchit, an inward friend of Johnson’s, was enlisted for the purpose of “secret training.” Ali was particularly interested in a Johnson move called the anchor punch, a short, twisting jab that took no longer to execute than the burst of a flashbulb, and could only be executed as an opponent moved in with force. Fetchit, who made his money and built a reputation presenting broadly comic images of lazy, mush-mouthed clowns swore he didn’t know how Johnson did it, but signed on to help anyway.

Like Ali, Johnson’s mouth was as dangerous as his fists. He was a masterful defensive fighter who strategically nullified his opponents arms in a way that forced them to overwork. Taunting opponents — particularly white opponents — while fighting them made them work that much harder, overextend themselves. He’d go into a clinch, delivering two to the body, one to the top floor, or he’d back up with his right hand batting at his opponent like a cat, left cocked close to the body like a tight spring ready to pop. Outside the ring he was even bolder, and Ali frequently expressed admiration for both the athlete, and the man saying things like, “Jack Johnson was a black man back when white people lynched negroes on weekends. Back in 1909 they’d send him letters saying, ‘You’re fighting a white man, and ni**er, if you knock him out, we’ll kill you. He’d say, ‘just kill my black butt cause I’m gonna knock this white man cold.”

Muhammad Ali Meets Stepin Fetchit at The Hattiloo Theatre (2)

Similarly, Stepin Fetchit (born Lincoln Perry), who was 20-years younger than Johnson, and who shrewdly and deliberately traded Vaudeville for a career in Hollywood less than a decade after Birth of a Nation, has to be understood in a hostile climate and context — and with the full understanding that, at the same time, black artists like Langston Hughes, Paul Robeson, and Paul Laurence Dunbar chose to make definitive African-American statements over Hollywood salaries.

But was Fetchit’s clown as reprehensible as emerging comedian Bill Cosby made it sound in 1968 when he appeared in the Andy Rooney-penned documentary, Black History: Lost, Stolen, or Strayed? Cosby, a frequent moral scold whose own reputation has come under fire in recent years, described Fetchit as, “The traditional lazy, stupid, craps-shooting, chicken-stealing idiot.” Gentler critics have found a lineage of subversion in otherwise hard-to-defend routines, by placing Fetchit’s work in the long tradition of stock servant characters who pretend laziness or incompetence to trick masters into doing the work for them — a kind of comedic rope-a-dope echoing, faintly at least, the sweet science of both Johnson and Ali.

Muhammad Ali Meets Stepin Fetchit at The Hattiloo Theatre (3)

It’s difficult to imagine any common ground between the physically and rhetorically powerful Ali and Lincoln Perry’s submissive sleep-warrior Fetchit. Then again, our understanding of race and pop-culture continues to evolve and comparisons of Ali to Johnson that were once dismissed as superficial seem evermore apparent in hindsight.

Fetch Clay, Make Man is running at the Hattiloo through Oct. 15

Muhammad Ali Meets Stepin Fetchit at The Hattiloo Theatre (4)