Ta-Nehisi Coates is one of the most celebrated wordsmiths of the day, and for good reason. To commit an understatement, he is enchanting, erudite, and prolific.

Coates has been called America’s preeminent authority on race. The author of the memoir Between the World and Me and the essay collection We Were Eight Years in Power, he has written about African-American history and white supremacy. At the helm of Marvel’s monthly Black Panther series, Coates has taken T’Challa through civil war, natural disaster, and into the Intergalactic Empire of Wakanda. A mark of Marvel’s faith in Coates’ storytelling ability is that, two years after he began his run on Black Panther, the company gave him the reins to Captain America, effectively putting two of their most powerful and profitable supersoldier eggs in one basket. So when Coates announced the upcoming release of his first novel, a magical realist take on the antebellum-era American South, suffice it to say that this reader’s expectations were high.

Gabriella Demczuk

Gabriella Demczuk

Ta-Nehisi Coates

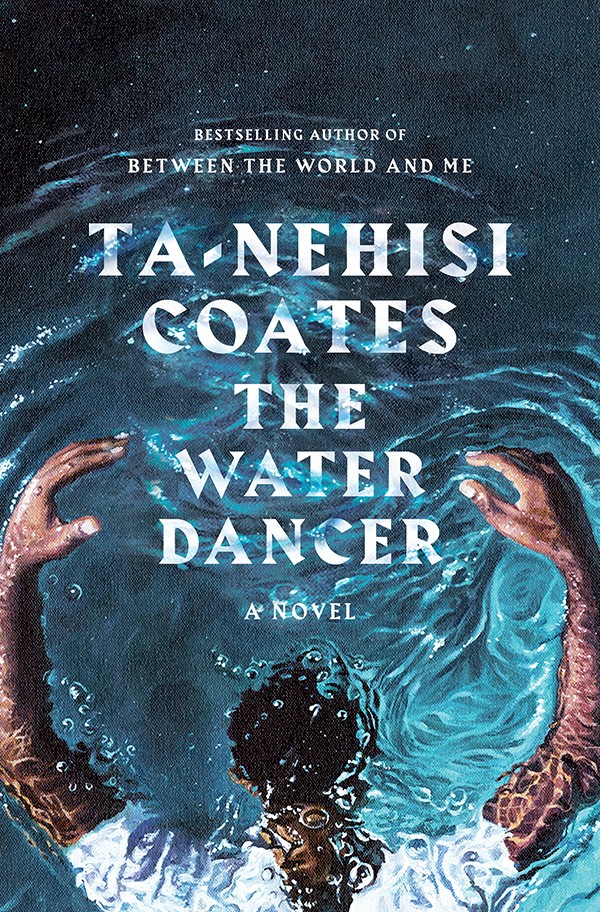

Those expectations have been met and far exceeded by The Water Dancer (Penguin Random House).

The Water Dancer tells the story of Hiram Walker, a slave — or, in the parlance of Coates’ world, one of The Tasked — the son of the white owner of a Virginia tobacco plantation, and Rose, a slave and the greatest dancer in Virginia. The plantation Lockless, though, is in decline, with tobacco yields steadily falling, and when Hi was 9 years old, his mother was sold. That unnatural separation haunts Hi. For, though he has a photographic memory, he cannot recall his mother. And those stolen memories may be the key to Hiram’s more exceptional, even supernatural talent.

From the field workers’ refrain of “Remember me and my fallen soul” to Hiram’s gift of recall and his suppressed memories of his mother, memory is the Greek chorus of the novel. It is crucial when present and remarkable in its absence. Hiram is one of a multitude denied the dignity of memory. Their histories have been fractured as family members have been separated and sold.

As Hiram falls in love with Sophia, another of Lockless’ Tasked, he is compelled to fight the system that stole his mother from him and that stands to take away any other love he might find. “Natchez-way was worse than death, was living death, an agony of knowing that somewhere in the vastness of America, the one who you loved most was parted from you, never again to meet in this shackled, fallen world. That was the love the slaves made.”

While Hi navigates a world of conflicting ideologies, Coates juxtaposes the fractured histories of the Tasked with the self-serving mythologies of the Quality. “We got a duty to save our country,” Hi’s father tells him. “The country your grandfather carved out of wilderness will not return to the wild.”

Coates’ prose is poetic, resonating with a longing seemingly too powerful to put into words, the desire for family and home. It’s a testament to Coates’ power as a writer that, for all the research that went into The Water Dancer, it is a novel that works at the reader’s heart as much as their head. “Knowing now the awesome power of memory, how it can open a blue door from one world to another, how it can move us from mountains to meadows, from green woods to fields caked in snow, knowing now that memory can fold the land like cloth, and knowing, too, how I had pushed my memory of her, into the ‘down there’ of my mind, how I forgot, but did not forget, I know now that this story, this Conduction, had to begin there on that fantastic bridge between the land of the living and the land of the lost.”

With The Water Dancer, Coates has a deft touch as he confronts the nation’s myths. In a sense, as both a journalist and a comic book writer, Coates has been in training for much of his career to write this novel. It’s no wonder, then, that it reads as if it was not written, but dreamed into existence.