For this edition of Never Seen It, I was invited by Memphis Flyer Senior Editor Jackson Baker to join the Political Cinema Club for a Studio on the Square screening of 1984. The Political Cinema Club is not a formal group so much as a loose, rotating bunch of cinephiles who work in politics and sometimes get together for movie nights.

The film was a big screen adaptation of George Orwell’s seminal science fiction novel by director Michael Radford. It was shot during the exact same period of time that Orwell, writing in 1948, set his novel: April-June, 1984. It starred John Hurt as Winston Smith, Suzanna Hamilton as Julia, and Richard Burton, in his last role, as O’Brien. It was also one of the earliest feature films shot by Roger Deakins, who would go on to produce visual masterpieces such as No Country For Old Men and Fargo with the Coen Brothers.

The film was recently re-released for a week’s theatrical run, and it proved to be terrifyingly relevant to our current political situation. In addition to me and Mr. Baker, the group consisted of Reginald Milton, County Commissioner, District 10; John Gammel, a retired civil servant, artist Peggy Turley; Steve Mulroy, Associate Dean at the University of Memphis School of Law and a former County Commissioner, and David Cocke, Democratic activist and lawyer.

Peggy Turley: I knew nothing about this film. I don’t know where I was in 1984.

Chris McCoy: It was a laugh a minute!

PT: I feel beaten down. It wasn’t easy.

Jackson Baker: That was what you’d call ponderous, actually.

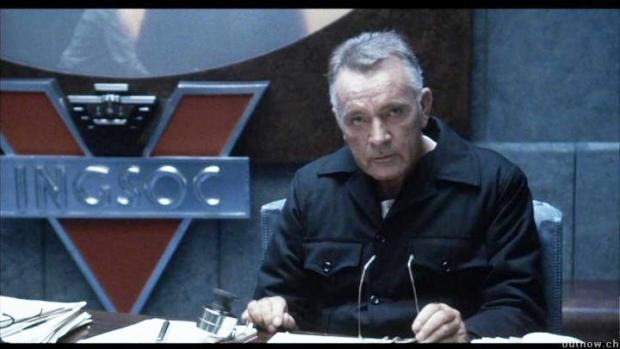

Richard Burton as O’Brien in 1984.

John Gammel: I didn’t know that was Richard Burton’s last film.

PT: He was almost unrecognizable. His eyes and his voice were the only recognizable things.

JG: And John Hurt, he was accused of being 45 in the movie, but if he was 45, he was rode hard and put up wet.

Chris McCoy: It’s like he was born old.

JB: It took an effort of imagination to see him with her! (Suzanna Hamilton, who played Julia)

CM: Griding dystopias will take it out of you. Had you ever seen it before?

JG: I think I tried to watch it once, but it gets off to a slow start…

CM: You were like, “OH MY GOD, WHAT IS HAPPENING?”

JG: It’s a little grim.

Suzanna Hamilton as Julia

CM: Steve, have you ever seen the movie before?

Steve Mulroy: No. I read the book, of course.

CM: Everybody reads it when they’re young. I read “Politics and the English Language” when I was about nine years old. Way too young.

SM: I think I read it when I was a freshman in college for a politics and literature course.

CM: I was a kid who read sci fi compulsively, and the essay was in the back of my copy of 1984. So what did you think?

SM: It was about what I expected. A slow, ponderous, depressing treatment of the subject, that would be visually interesting, because I read about that color thing they did. [A process known as “bleach bypass” was used on the film, which creates a washed out, desaturated color palette while retaining the sharpness of the image.] It reminded me of the [Francois Truffaut] adaptation of Fahrenheit 451. I admire them for tackling such difficult and important work, and of course the work itself has a great message and is historically important, but as cinema, I dunno. It was hard to take.

CM: Hitchcock said that mediocre books make the best movies. You can’t make a great movie out of a great book, because it’s too dependent on the language. In this case, 1984 the book is all exposition.

SM: It’s all going on inside Winston’s head… How many times did you read the book?

CM: Seems like eight or nine times. It was one of my faves. I think it may have influenced me a little too much. But I haven’t read it in a long time. I remember that there was more than one visit with O’Brien in the book.

SM: He also did a better job in the book of establishing Winston’s deep seated fear of rats. There were times that a rat would appear in the apartment, their love nest, and he would freak out. So by the time they did the horrible torture in the end, it was already baked in. In this one, it seemed like it came out of nowhere.

CM: The imagery was there. He went back and his mom was not there, but the rats were there.

SM: Hurt is a fantastic actor. He had absolutely no vanity in making himself look horrible. Richard Burton did his usual job, but it kinda felt like he was phoning it in.

CM: The idea of Richard Burton is always better than actual Richard Burton. Except for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf.

[We decamped to Bosco’s for beers and a more intense discussion]

JB: Do you remember the scene in Cabaret, where the Nazi gets up and sings “The future belongs to me” and the old folks are looking like, what’s going on? That exactly paralleled the opening scene. There were older people in the audience who were looking bewildered.

CM: How the kids were portrayed throughout is the creepiest part.

JG: Although the kids looked not as grim. Life for everyone in the outer party is pretty grim. They’re all in blue uniforms, and devoid of anything happy. The kids at least are clean.

CM: They seem to be enjoying it.

JG: They’re cleaner and they’re happier. Everyone was dirty. I just wonder, in our world, it’s so bright and shiny. For me, that was a real question. If you took all of the grimness out of that movie, what would be left?

CM: You mean the visual grimness?

JG: I mean the grimness of life. People were living lives that were tiny.

JB: The Nazis at least could craft a good story. They took care of their kids. They took them on cruises and played around. There were fairs and festivals that brought the people together, going beyond the nasty torchlight assemblies. It portrayed a situation so dystopian, I could not believe in it. There has to be a carrot…

CM: In a successful dystopia, there’s a carrot as well as a stick.

JB: If that’s how you define success for a dystopia.

SM: That might be a criticism of dystopias in real life. In the book, it was all stick and no carrot. It was as grim in the book as it was in the movie.

JB: It is a criticism of Orwell, but it really came across in the movie.

CM: The carrots are for the Inner Party.

SM: Orwell’s point, though, and it may not be convincing—Jackson, I don’t think is convinced—is that if you constantly rewrote history, and constantly changed language, with new editions of the dictionary, slimming it down, you can do such an effective job of brainwashing people that maybe you wouldn’t need the carrots any more. You could so completely brainwash people and control their thinking that your dystopia would still work.

JB: When that movie came out, I was working in Washington DC working for a Democratic congressman. It was 1984, and Reagan was president. The reason I never dragged myself to see the movie was, I figured if 1984 was about a dystopia, well, we already had the dystopia! We already had morning in America. We already had the Evil Empire. That dystopia was organized around greed. If you’re going to do that, you have to have a carrot.

CM: Does everyone always think they’re living in a dystopia? In 1984, you thought “Wow. We’ve hit rock bottom. This is no longer America…”

JB: It could have gone further, and it did!

SM: Every time you think we’ve hit rock bottom, it gets worse.

JG: I thought I was living in a dystopia until I moved to Memphis

David Cocke: First of all, it’s all relative. Orwell was just coming out of the worst totalitarian episodes, with World War II and Russia. His model was Communism.

CM: He was a disillusioned socialist.

DC: But even in France you had totalitarianism during the war. It was a whole experience of living in this grim, warlike, thought controlled society.

JB: Have any of you read Homage to Catalonia, Orwell’s book about his experiences during the Spanish Civil War? It was incredible.

DC: The thought control, the conformity that warps the independent mind, exists not only in the grim totalitarian moments, but also in social conformity. There are elements in our culture today, but none of us feel like what we saw in that movie. I think the Vietnam War was the closest this country has come to that environment.

CM: You mean the state of constant war? Because we’ve been in a state of constant war for 16 years. There are kids today who can drive who have never known anything but America at war.

DC: I’m not arguing with you, but the number of people involved in the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the number of deaths assosicated with those wars is miniscule compared to Vietnam.

JG: In Iraq and in Syria? Civilian deaths have been…

DC: I’m not talking about civilian deaths. They are other people in another world. They are on TV, but they’re not us. What we saw on TV in the 1960s was our kids getting shot, not the Vietnamese getting shot.

CM: I know kids who I grew up with who did multiple tours in Afghanistan.

PT: In the film, they were constantly seeing images of war on television. But a lot of that was just theater, right? It was not necessarily real war.

DC: And our armies are professionals, by the way. They’re volunteering.

SM: I think maybe you’re both right. Orwell wanted just enough war to distract the populace and control the populace. Then he took it farther, and they were at the brink of starvation. But that’s not the real world model in America. The real world model in America is to have just enough war to rally everyone around the flag, but not enough to actually cause sacrifice on the part of the public. George W. Bush after 9/11 said, everyone go shopping. We’re supposed to keep the same standard of living, and keep in the back of their mind that there’s a war out there, and we all have to be loyal.

CM: It’s the invisible army against the invisible enemy. That seemed very familiar to me.

JG: I think the War On Terror is as close to that situation as is possible, really. The absence of real war is a part of it. The domestic impact of the War on Terror has been in terms of the whole militarization of the country, and how that affected policing. I mean, police have always been ruffians, to a certain extent, but they’ve never in history been as entitled. They have been totally militarized. What is it, evil empire…

PT: “Bad hombres” today.

SM: With Bush it was the Axis of Evil.

JG: Only after 9/11 did you hear majors and colonels going on TV and saying, “We’re going after the bad guys.” That’s not a military term. It’s “The enemy”. In the military, the enemy is honorable.

…

SM: I thought it was interesting in that, another way the film was faithful to the book was that the proles seemed less brainwashed and really happier. If there’s any hope, it’s from the proles. When you left the main sector and went into the forbidden proletariat sector, there was at least some genuine happiness. Even the old washer woman who was singing a propaganda song created real beauty. That was the one shred of hope.

JB: There was a lot more of that in the book than the movie.

DC: In other words, it was the middle class who took the brunt of the dystopia.

JB: If you want a real example of an Orwellian dystopia today, look at North Korea.

PT: Oh yeah. That’s why I don’t think there’s a need for carrots. They are dark and beaten down, observed, and controlled.

Reginald Milton: I agree with you on that. To the elites, the enemy is actually the people themselves. There is a group who are empowered and who have a good quality of life, and everyone outside of that is the real enemy.

JB: We are their Eurasia.

RM: Right. North Korea is the same. It’s basically using people as tools to prop up a very small segment who are enjoying a high quality of life. Then there’s the situation in Cuba, where, when President Obama opened up relations, the Cuban government still attacked Obama, because at the end of the day, they still had to have an enemy. If they didn’t have an enemy, the people might go “Wait a minute, who IS our enemy? Who is to blame for all of these problems?” So the reality is that, this is how it’s always been. Imagine a boot, stamping on a human face, forever. That’s exactly what the North Korean government is. It’s an oppressive government that caters to a small segment and uses the masses to maintain them.

Never Seen It: Watching 1984 with the Political Cinema Club (2)

CM: The Eurasian government, and the East Asian Government, and the Airstrip One government—the inner parties in all three of those have more in common with each other than they have with the people they are supposed to be governing. They’re all using the same tactics to maintain power.

DC: In the book, were they real? Or were they manufactured?

CM: They were real, and the war was real. They would have skirmishes, but they weren’t having a war where they were trying to win. It was perpetual war to keep the people in line.

DC: Well, that’s what we have in this country now, right?

CM: Yeah. The idea was to eat up the excess economic production.

PT: It’s like what just happened, with the missile strikes in Syria.

SM: This is the first time I’ve actually wondered if it was real, though. Under W., I never doubted that they honestly, sincerely believed their line about evildoers. There were neocons who wanted to remake the Middle East in their own image, and they were using terrorism as an excuse. But they definitely wanted a real war. With Trump, I don’t know what he wants. It might not be real.

CM: Reginald, your point about how there has to be an enemy applies to Trump. When he started flailing was when he suddenly didn’t have an Obama or a Hillary to push around any more. They keep trying to push Hillary and Obama back out into the news, because they need an enemy, or else his incompetence becomes obvious.

JG: Best case in point: Gun sales are down 26%.

DC: The reason they were hoarding the guns is that they were afraid the liberals were going to take over and take them away. Now they don’t need them.

JG: The NRA made a deal with the Kalishnikov factory to lobby to get restrictions on their sales lifted in the United States.

CM: The elites have more in common with each other than they do with their own countrymen.

SM: Just like the pigs and the famers had more in common with each other than they did with the other animals in Animal Farm, which is also Orwell.

CM: That’s the children’s book version of 1984.

SM: Jackson said earlier about the carrots and the sticks. I think the carrot model of dystopia is Brave New World, where everything is bright and shiny, and they used drugs to control the populace.

JB: I think that’s closer to where we are.

CM: Here’s to soma!

ALL: Cheers!

[This fascinating conversation went on for another hour, and there was much more than I could possibly transcribe, so I will leave it here.]

Never Seen It: Watching 1984 with the Political Cinema Club