Sean Young is smoking hot as Rachel in Blade Runner.

Josh Campbell is the host and co-founder of Spillit, the popular Memphis storytelling slam event. He and his son Paul, 16, have a podcast on the OAM Network called “Dad and I.” Since the coronavirus quarantine started, Josh and Paul have been watching classic movies together. I joined in (virtually) to watch a film they’ve never seen, Ridley Scott’s 1982 masterpiece Blade Runner. I edited our conversation for length and clarity.

Chris McCoy: Let’s start with you, Paul. What do you know about Blade Runner?

Paul Campbell: I know there’s a remake.

Chris: It was really a sequel.

Josh Campbell: He’s a Ryan Gosling fan.

Paul: I haven’t seen that one, either. But that’s about all I know about it. I don’t know anything about the original.

Chris: Okay! Josh, what do you know about it?

Josh: It’s funny. I’m a big Harrison Ford fan. I think I’ve seen everything else with Harrison Ford in it. But I think I was six when this movie came out. It’s known as one of those movies that’s made predictions about the future, and it was one of the first science fiction movies to have a gritty view of the future as opposed to sort of the clean look some of the other sci fi movies have. I guess I’ve just avoided it because of the prediction aspect of it. Any time a movie makes predictions of the future, the further you get into the future, it’s kind of tough to go back and look at what the predictions were.

Chris: Well, that’s interesting, because I want you to the notice the opening titles. It says that the film is set in November, 2019. So this film is actually set in the past now.

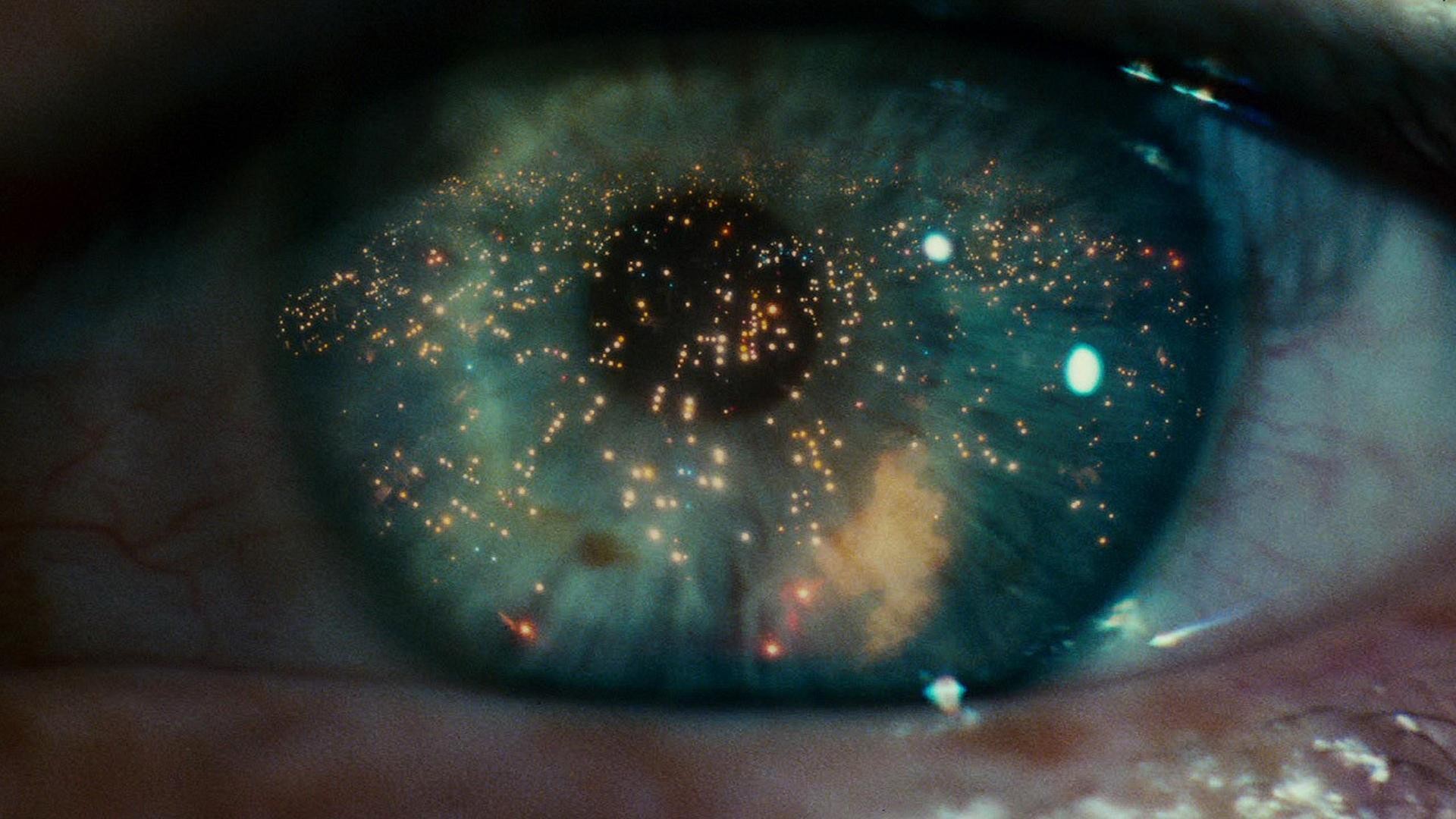

The opening shot of Blade Runner.

117 minutes later, more or less…

Chris: Josh and Paul, you are now people who’ve seen Blade Runner. What did you think? Paul, go for it.

Paul: It was good. It looked really cool. I was just wondering, why was it so dark the whole time?

Chris: Yeah, I know. And it seemed to rain an awful lot for Los Angeles.

Paul: Why didn’t anyone light their homes?

Edward James Olmos as Gaff enjoying a sunny day in Los Angeles 2019.

Josh: I thought it was definitely like a film noir. It was like there were two movies going at the same time. It was like a 1940s detective movie, and sort of a Frankenstein movie happening, like, side by side.

Chris: Paul, there’s your answer for why is it so dark all the time. Because it was heavily influenced by film noir. You know, like, detective movies. So, tell me about your poster and your movie-watching project that you’ve been doing.

Paul: So, it’s got a hundred little spaces that work like a lottery tickets. We can scratch them off, and there’s a hundred movies on there. It’s like a bucket list. I have gotten through 40-something of them so far. But they’re all great.

Chris: Did you watch a lot of movies before now?

Paul: Yeah, I try to watch a lot of movies. I try to watch all the ones that people say are important or whatever, you know.

Chris: Did Blade Runner feel like one of those?

Paul: Yeah, it felt really advanced for how old it was. ‘Cause you look at a lot of old movies and they don’t feel super futuristic. And while this one still has small TV screens and stuff like that, it still feel really futuristic to me.

Downtown Los Angeles in Blade Runner (1982)

Chris: One of the old questions is, did Blade Runner look like the future, or does the future look like Blade Runner? Because all the designers grew up watching this movie, and everybody ripped it off. I think the first movie to really rip it off was Akira, the anime, in 1988.

Paul: We were trying to find that one, but we haven’t found it yet. It’s on the poster.

Neo Tokyo in Akria (1988)

Chris: The weird thing about this movie is that it completely bombed when it originally came out. Apparently, the entire production was a complete nightmare from start to finish. Ridley Scott and Harrison Ford hated each other, and there was a crew rebellion at one point. There was so much smoke. It was everywhere. So the crew was in respirators for six months, and people got lung damage and stuff.

There was a cut of the film that Scott had turned into the studio and was like, okay, well, this is the movie. And then the production company basically fired Ridley Scott. You know the bit with the unicorn?

Never Seen It: Watching Blade Runner with Josh and Paul Campbell (4)

The reason that’s there is because Ridley Scott had kind of given up on this movie.

JC: Yeah! He was doing Legend next.

Chris: The unicorn was a test shot for Legend, but he used Blade Runner money to do it, because he was trying to sell Legend at the time. So he stuck the bit with a unicorn in there because he was just like, “I don’t know, it means something. Who knows?”

The unicorn co-stars with Tom Cruise, and Mia Sara in Legend.

So the production company takes it away from him, and they make Harrison Ford do a voiceover that basically explains everything that’s happening. And they cut a whole bunch of stuff out, too. That was the cut released to theaters, like, two weeks after E.T. And of course, E.T. became the highest grossing movie of all time. So nobody went to see Blade Runner. Everybody kind of forgot about it.

Never Seen It: Watching Blade Runner with Josh and Paul Campbell (3)

Then, in 1990, they were having a 70 millimeter film festival in Los Angeles. Somehow, the print of Blade Runner that they got was the work print. It wasn’t the theatrical cut with the voiceover. So this audience goes in, and they watch the cut without the voiceover on it. And they were like, “Oh my gosh, that was so amazing!” That’s sort of where the legend of Blade Runner started. It was like the Velvet Underground and rock and roll. Ten people bought the first Velvet Underground album, but every one of those people started a band. It became hugely influential.

Josh: In most futuristic movies, they try really hard to make the world look all the same. If you look at some of the apartments they walked into, they look like old, 1940s apartments. Then other apartments look very futuristic. It would be almost like it is today, in 2020. You know, here in Midtown, you go out and find bungalows that were made in the 1920s, and then there’s tall, skinny houses right next to them.

Harrison Ford as Rick Deckard, making dinner in his kitchen.

Chris: Blade Runner is based on a book by Philip K, Dick called Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? It was written in the late 1960s, but it was about two things: It was about environmental collapse, and it was also about artificial intelligence. What is the line between what is human and what is not human? How do we even know that we’re human? It’s very philosophical stuff. Dick was … he was just like that. I mean, this is a guy who eventually wrote his longest novel about how an extraterrestrial intelligence had psychically contacted him and given him a new perspective on the New Testament. He was a weird guy.

You know, one thing that’s interesting is that nobody predicted smartphones. There’s still pay phones in Blade Runner. They’re video phones, but they’re pay phones. Nobody got cell phones. Star Trek did, but then nobody else did.

Never Seen It: Watching Blade Runner with Josh and Paul Campbell (5)

Josh: Well, I think again, that’s one of those little beats that were hit for the film noir aspect. It’s like, you know, the detective goes into the phone booth. Like all those things are tropes. Sean Young was perfect as a femme fatale, dressed almost like Joan Crawford. That’s something Paul and I talk about a lot. He was brought up on the Avengers movies. What we talk about is how Marvel movies have become the way to make other movies. And instead of being a genre movie, it’s just a way to do other genres.

Paul: Captain America movies are like Bond movies. Guardians of the Galaxy are like science fiction movies. And Ant Man is a comedy.

Josh: So to me it is interesting, to see a sci fi movie that was trying to be like a genre movie in a different genre.

Chris: And it was, like, reintroducing noir. The big crossover with sci fi has always been westerns. There’s a big Western influence on Star Wars, for example. You know, Han Solo is like a gunslinger. Especially at this stage, putting noir in science fiction was something that just wasn’t done. Paul, have you watched much noir on your quest?

Paul: I don’t think I’ve seen any yet. I’m not really sure though. Well, I guess we watched Seven.

Josh: Yeah. He’s not into the black and whites, so we haven’t gotten into that era very much.

Chris: Paul, let me ask you, why don’t you like black and white?

Paul: I don’t know. It’s just kind of with a lot of action movies, there’s a lot of color happening, and it’s really fun to look at. It’s kind of harder to capture big action happening, and make it look like it’s actually happening, in black and white as it is in color. But when we watched Twelve Angry Men, I really liked that. It was just people sitting in a room talking.

Josh: But we watched Raging Bull, too. What do you think about Raging Bull‘s action?

Paul: It was good, but I also didn’t feel the action naturally. I liked the stuff with his family.

Chris: It’s about the shadows too. A lot of Blade Runner is about where the absence of light is as much as it is about where the light is playing. You know what I mean?

Paul: Yeah. But then the neon in there, so it sticks out so much in that too. When there’s some scenes where it’s black and white, but it’s almost like blue and white or red and white or red and black or blue and black.

Josh: There was this idea in the eighties that Japan was buying up America, and that Japan was going to be the superpower, and that we were going to live in their world. Most people in Los Angeles seem Asian, and all of the signs are in Chinese or Japanese, I think. Was that in the book, or was that the movie coming up with that?

Chris: That wasn’t in the book at all. That all came out in the movie. There’s one way to interpret that, which is, Decker lives in Chinatown, so that’s why you see so much of it. But if you think about it, that is one thing that Blade Runner got close to right. If you think about all the anime that’s huge with people younger than us, Josh. I mean everybody watches anime, right Paul?

Paul: Yeah. I never got into it, because it takes way too much time.

Chris: K-pop is huge too. Here we are in 2020 and Asian popular culture is really huge. So they, they kind of got that right.

Paul: Yeah, at least that part.

Street sushi with Rick and Gaff.

Chris: Josh, you said that this is one of the few Harrison Ford movies you hadn’t seen. So what’d you think about him in this movie?

Josh: The thing that I like about Harrison Ford is when he’s playing a vulnerable hero. I think he’s really good at that. There’s so many times, especially like in the Tom Clancy movies, where he just gets beat up a lot. He, he’s almost like a Humphrey Bogart-type character actor that got pushed into super-big blockbusters by accident. If you take Indiana Jones and Han Solo and Jack Ryan out of it, and you look at movies like Witness or Frantic or any of those movies where he is kind of like an everyman. I think he does really good at that. And his facial expressions, he looks like my dad.

Paul: He looks a little like granddad.

Ladies, Harrison Ford has some questions for you.

Chris: I think that one thing that doesn’t age well about this movie is the interpretation of his relationship with Rachel, with Sean Young. I think it feels really uncomfortable. In the book it’s even weirder, but I think it’s better. In the book, she is the aggressor in the situation. Once she figures out she’s a machine, that she’s a replicant, she wants to go seduce him to prove to him that she’s just like a human. He’s the guy that’s going to go around killing replicants, and she’s trying to convince him that what he’s doing is wrong. But he just thinks of her as a machine.

Josh: Paul, that’s one thing that when we watched all of these movies like from, I would say 2000 back. The sexual politics are always awkward. Sometimes, it’s so casual, I would not even notice it. And Paul will say, ‘Whoa, what’s this guy doing?’

Paul: Right. Yeah.

Josh: We see that a lot. And it’s like, well, that’s how it was. It’s hard to explain that. So when he’s saying like, “Say you want me”? Yeah, that hasn’t aged well, but a lot of that stuff is not age. That’s always a little queasy when you’re looking at that.

Harrison Ford and Sean Young

Josh: I’ve always heard that there is a little bit of, is he a replicant? That was part of the twist or whatever. Cause she says, “Have you ever done that test on yourself?”

Chris: Yeah. And then he goes and looks at his photographs, just like the replicants had.

Josh: So I kept waiting for that big reveal, that maybe he was in danger.

Paul: Well, it never really says, yeah, I didn’t think so.

Josh: But didn’t it come across like that to you, Paul? You didn’t think he was a replicant?

Paul: That he was a replicant, no. But I don’t know. I thought they would answer that eventually, when she brought that up. I don’t really know. I don’t think he is.

Josh: And then the origami thing, when I saw the unicorn in the shot and then I saw the origami unicorn, I thought that was some sort of totem of like, I know his memory. [Gaff] knows his memories, and every time he left something for [Deckard], they were positioning him, in a way.

The infamous origami unicorn.

Chris: I think that’s in there. I think it was left intentionally ambiguous. Part of Phillip K. Dick’s purpose in writing this thing in the first place was to make you question the nature of your own reality. The humans feel like, because they created these replicants, and that they are quote unquote artificial, that they have the power of life and death over them. They can make them slaves, they can make them pleasure units, they can do whatever they want with them.

But they also made these replicants to have humanity, and they’ve realized that they’re developing feelings, too. At what point do you cross the line between, this is a machine, and this is something that’s like me? How much do you know about your own consciousness? You can say, this is machine. It’s just a whole bunch of preprogrammed subroutines that interact together to make it look like it’s a thinking, feeling person. But then, if you think about yourself, maybe that’s all I am, too. Maybe I am just a bunch of separate instincts that interact together and believes it’s a person, believes it’s special, and believes it has the power to do whatever it wants. So I think leaving it vague, as to whether Deckard is a replicant or not, that’s part of the artistry of the thing, you know?

Rutger Hauar in his career-making turn as Roy Batty, the android who wanted more life.

Josh: Talking about the pacing of eighties movies, what was the pacing like for you?

Paul: What do you mean?

Josh: Are you always like, let’s get it going?

Paul: It did take a while to kick in. Yeah. But I think it was really cool to look at, so it didn’t really bother me that much as it usually does. But you know, it also feels like back then dialogue was a lot different in action movies. Dialogue’s always different in action movies. It’s never like just like, “Hey, what’s up? Hey, how you doing?” Everything’s really written out. I liked that. I thought visually, it’s awesome. Some of those shots were really cool. I know how the voiceover would have been to me. I can see why people reacted to it the way they did, because the voiceover would have grabbed you out of it.

Chris: I’ve got all the different versions, and if you watch the theatrical cut, Harrison Ford so clearly phones it in. He’s just like, yeah, whatever, you know, here I am because of my contract. It’s not like Double Indemnity, where the voiceover is so dramatic.

I’m glad that you brought the pacing up because, this is a slow movie. In 1982, this was a slow movie. But I think Paul, it’s really interesting what you said, that it didn’t bother you, because there was so much stuff to look at. It kind of shows you what pacing really is. It’s not even necessarily like how fast the plot is going or, or how fast the cuts are. It’s all about the pace of information that’s reaching you from the screen. And so, even though the cuts are slower, and there’s not as much dialogue, there’s so much stuff to look at that your brain keeps engaged. It pulls you forward and it makes you want to keep watching. I think that skill in modulating that rate of information exchange is the most valuable thing a film director can have. And I think that’s also true for being a writer, too.

So, would you recommend it to other people?

Paul: Yeah, it was OK.

Never Seen It: Watching Blade Runner with Josh and Paul Campbell (2)