New DNA testing has been requested in the West Memphis Three case for recently rediscovered evidence once claimed to be lost or burned.

Damien Echols, one of three convicted of 1993 murders committed in West Memphis, asked the Crittenden County Circuit Court to allow the review in a petition filed Monday. Specifically, he wants the ligatures — the shoelaces used to tie the young victims’ arms and legs — to be tested with new DNA collection technology.

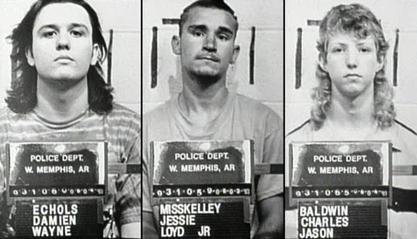

Echols hopes new clues from the analysis could exonerate himself, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley, known collectively as the West Memphis Three. The three were teenagers when they were accused and convicted of the murders of three younger boys, Steve Branch, Christopher Byers, and James Moore. The West Memphis Three were released in 2011 after they entered Alford pleas, which allowed them to claim their innocence but also admit prosecutors had enough evidence to prove their guilt to a jury.

“Echols knows that his DNA is not on those ligatures because he had no role in committing these murders,” reads the petition from Echols’ attorney Patrick Benca of Little Rock. “Others might not be so certain, though, and who those others are surely needs to be determined if it can be ‘in the interests of justice.’”

The petition comes after evidence in the case was rediscovered in December. Echols tweeted at the time that “we know that none of the evidence was destroyed,” and “my attorney was in the evidence room this morning and saw it with his own eyes. Every piece is still there.”

The petition also outlines the tough and lengthy process required to find that evidence; namely, the ligatures used in the murders. In 2020, a true crime documentary asked if new DNA testing methods might yield new results in the case. Scott Ellington, the prosecutor in the case, “balked” at the idea at the time, according to the petition.

One of Echols’ attorneys later asked Ellington about testing the evidence again, and at that time the prosecutor “had no problem” with the idea. The two agreed on the evidence to be tested: “the victims’ shoes, socks, Boy Scout cap, shirts, pants, and underwear, as well as the sticks used to hold the clothing underwater, and the shoelaces used as ligatures to bind the victims,” according to the petition. They even selected a private California laboratory to run the tests. But none of the evidence was ever transferred, no explanation was ever given, and “it just never occurred.”

In March, Ellington was elected to a new position. He was replaced as prosecutor by Keith Chrestman, to serve until the end of 2022.

Chrestman, the new prosecutor, told Echols’ attorney that some of the evidence in the case had been “lost” after the three entered their Alford pleas. Some of the evidence was “misplaced,” according to the court papers, and some of it “was destroyed by fire” in a building fire.

Chrestman also told attorneys that the court had jurisdiction over the evidence and those officials would have to grant authority to see it. Still, he asked the West Memphis Police Department (WMPD) to catalog any remaining evidence. Chrestman did not respond to emails or requests from Echols’ attorneys after April 2021, they said.

Those attorneys filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request against the WMPD to see the evidence. In fall 2021, West Memphis city attorney Michael Stevenson invited Echols’ attorney, Benca, to a WMPD evidence storage facility “to ascertain what was there and what was not.”

“That visit proved productive with the finding of the most important evidence for present purposes — the ligatures used to bind the murdered children — misfiled at the police department,” Benca wrote in the petition.

Echols and his attorney are now asking for those ligatures, the little boys’ shoestrings, to be tested using the “M-Vac system.” Company officials describe it as “kind of like comparing a hand broom to a carpet cleaner,” when it comes to collecting material that might contain DNA.

Benca said the shoestrings already provided biological material used as evidence in the case, which is not surprising “given that the ligatures are the pieces of evidence that we can most confidently say were necessarily handled by the killer(s) who wrapped them around the victims’ limbs and then knotted them into place.”

“No one knows, of course, whether additional testing of the ligatures with the new M-Vac DNA collection technology will lead to the recovery of new DNA samples for testing or not,” Benca wrote. “But one thing for certain is that such evidence will definitely not be found if testing with this new technology is not done.”