This post is so going viral. I mean, who among us doesn’t get crazy excited about new editions of classic plays by authors like William Shakespeare and Henrik Ibsen?

I’ve already written a bit about Pelican’s new Shakespeare collection. But I feel compelled to jot a few words about Othello and The Taming of the Shrew. Both include the usual essays, with nice, lightly rendered introductions. Breaking a willful wife and training her up right was a popular plot back in Willie’s day and Shrew, we’re instructed, is part of that mysoginist genre, forever popular, but at odds with modern sensibilities. Othello‘s intro builds from the Shavian barb inspired by Verdi’s Opera Otello. In a spot on analysis George Bernard said Otello wasn’t Verdi’s most Shakespearian adaptation, so much as Othello was Shakespeare’s best Italian Opera. But honestly, I’m not here to type about what’s in the books, so much as what’s on them. I mean, it’s one thing to be bawdy, and quite another to be so on the nose. Or on the… something.

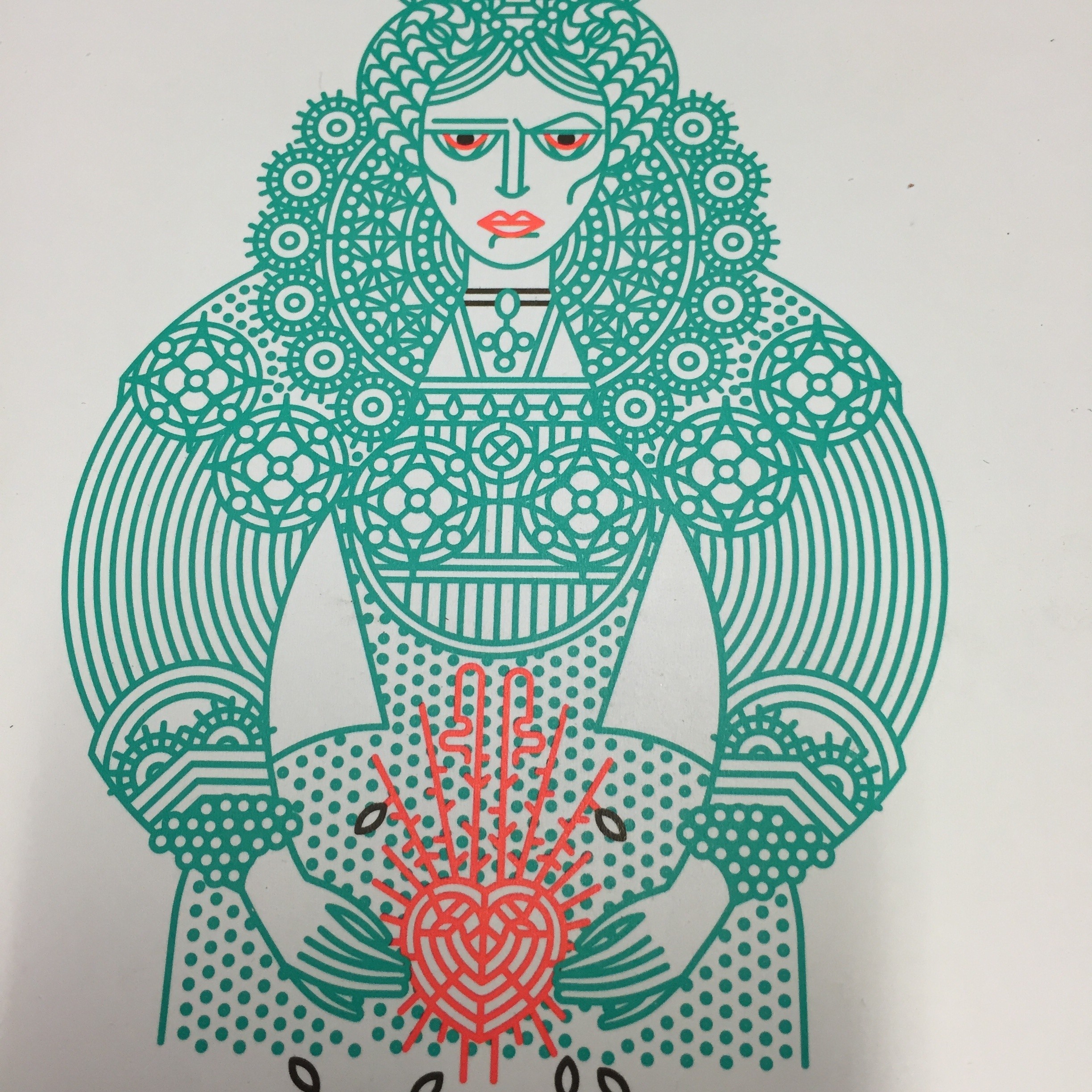

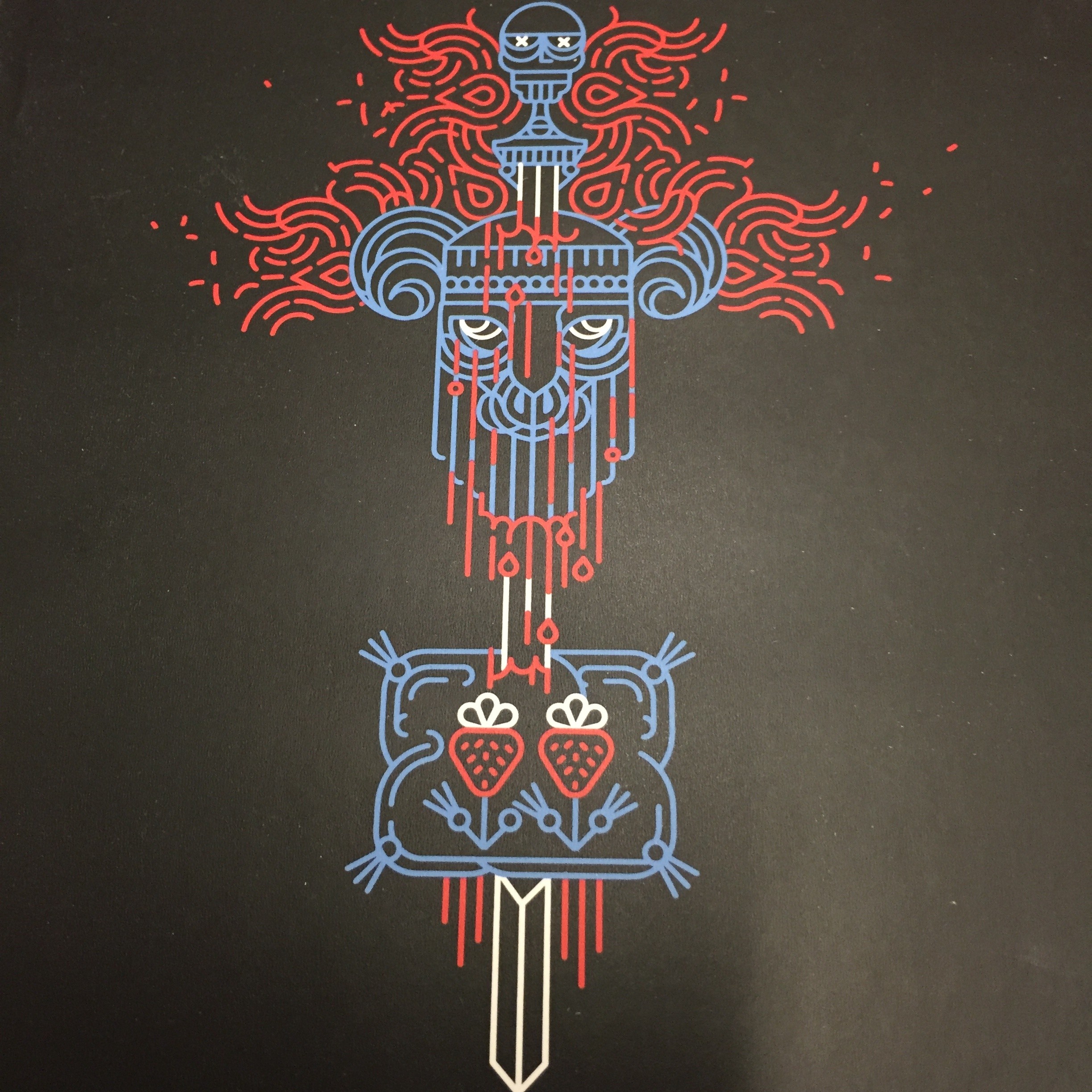

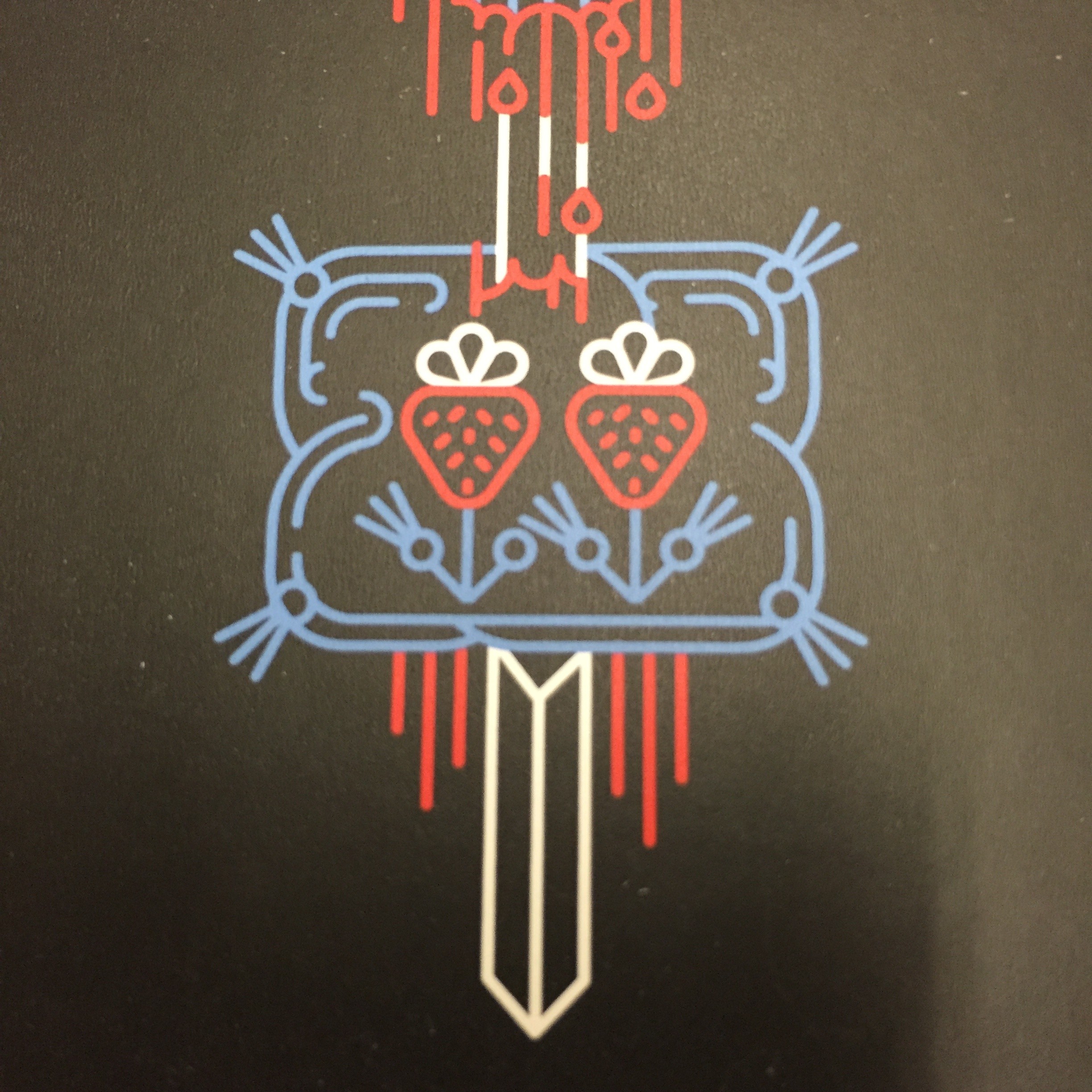

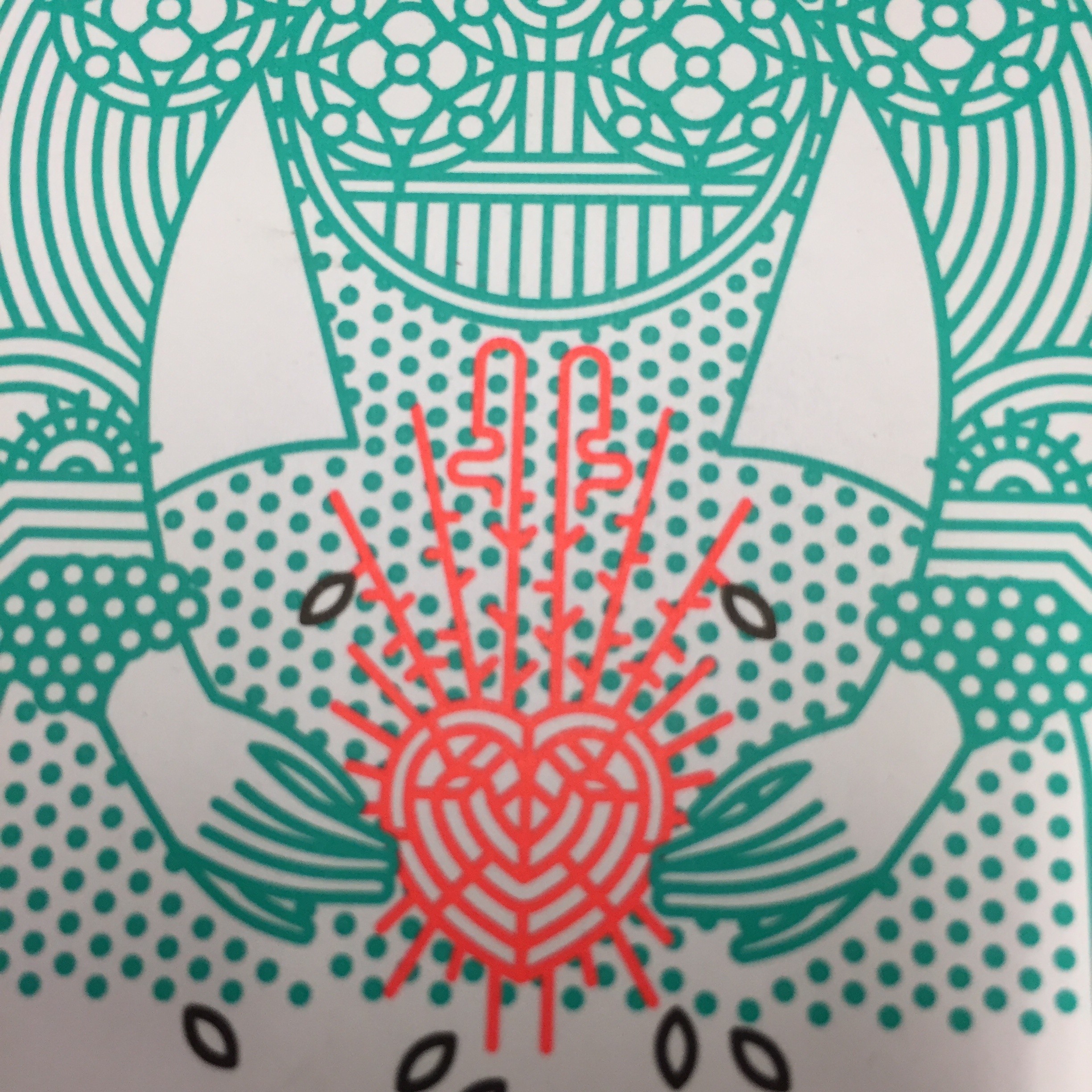

I’m not sure what it means to reduce the Moor of Venice to nothing but a head with a stylized penis, but here we are. Now here’s Kate the cursed on the cover of Shrew. What are all those little things around her her heartgina? Beads of sweat? Bugs? Just… Ew.

The scripts are fine, the essays are swell, but from the teeny tiny titles on, I’m just not loving this design.

Is it fair to call Ibsen Norway’s Shakespeare? Maybe not. Okay, no. But he was practically as inventive as the Bard when it came to word coinage and that can be a problem for translators. The new Penguin Ibsen collection isn’t just a new edition, it’s a new set of translations. That’s great news because we’re talking about an author who worked in a small language and is known primarily by way of translations, not all of which are historically sensitive.

It’s probably not so strange, given translation goals, that the publishers continue to use the title A Doll’s House even though that’s not quite right. In Norway “Doll House” is a distinct word, and one that Ibsen specifically rejected in favor of something closer to “A Home for Dolls,” which is less catchy, but bends the title’s meaning in a slightly different direction. Beyond this example where the title is too well known to alter, this is exactly the kind of thing the new editions aim to correct.

In addition to A Doll’s House the new collection includes Ghosts, An Enemy of the People, and an underrated early work The Pillars of Society.