At times, Nightcrawler is such an effective thriller that squirming in your seat is an involuntary reflex, like flinching at the bleeding leads on the nightly news. Writer-director Dan Gilroy’s new film lands several crude, short-armed jabs, and for a while it feels legitimately and bracingly crazy. But its buzz doesn’t last long, and once it wears off, all of the important questions it winks at — about photojournalism ethics, what it takes to make it in America, and what exactly is being satirized — are left unanswered.

Jake Gyllenhaal plays Louis Bloom, a down-on-his-luck psychopath drawn into the nocturnal realm of big-city news gathering, where any amateur with a van, scanner, and video camera can shoot bloody, intimate footage of the evening’s major murders and executions and sell it to local news stations for a tidy sum a few hours later. The film coolly follows this networking young man — a face in the crowd to die for — as he drives his taxi up and down Sunset Boulevard in search of that sweet smell of success.

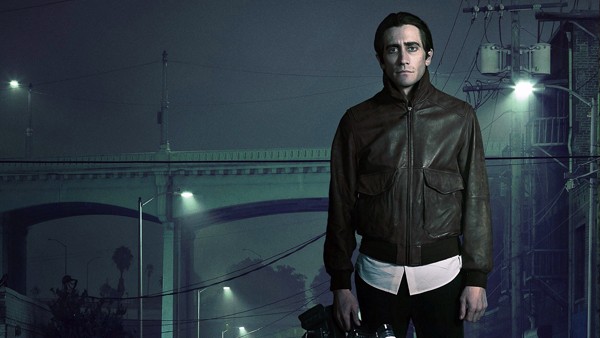

Jake Gyllenhaal in Nightcrawler

Bloom fascinates you even though he’s little more than a bug-eyed mannequin clad in self-help pull-quotes, motivational buzzwords, and polite platitudes, who says things like “working for myself is more in line with my skills and career goals” with a straight face. He’s a non-threatening shadow dweller pleasant enough to fade from memory but distinct enough to be suspicious. The cloistered, self-educated Bloom is a parody of someone who’s learned everything from spending day and night online, and occasionally Gyllenhaal hints at a cool, casual contempt for humanity as boundless as the internet itself.

The film takes place in Los Angeles, and Gilroy constructs a glowing, geographically savvy portrait of this great American city at night almost by accident. The bright digital photography here is nothing like the hazy, washed-out security-cam look of Collateral, Michael Mann’s L.A. crime flick from a decade ago. Cinematographer Robert Elswit’s primary colors are refreshing and sickly-sweet: the shots of video blue Chevron stations and neon signs blinking over the deserted early-morning streets are in some ways the film’s most significant cultural contributions.

Rene Russo plays Nina, Bloom’s weary television-producer boss, and she scribbles out a cocktail napkin-sized essay on fallen stardom in every scene. There’s a funny, tragic encounter when, out of nowhere, a casting couch virtually materializes in front of her while she nurses a watery margarita and listens to her new freelance darling’s Rupert Pupkin-like plans for world domination.

Bloom often holds his camera high above his head, as though he were about to bring it down on someone’s neck like an executioner’s axe: He constantly engages in shooting-as-stabbing, and his and Nina’s sexual thrill from a job well done is an important subtext. Gilroy’s suspenseful passages are similarly restrained. Yet they wring undreamt-of tension from watching Bloom watch other people, and something as simple and innocuous as a two-shot from an automobile’s rear-view mirror develops as much nervous energy as the scary, rollicking car chase that follows.