I think it’s time to add a new word to the dictionary: Beiged. Mr. Webster should define it as anything, but especially something reasonably exotic, made to seem boring and bland because of too much tan-colored pigment. For example: “Tribes is one of the most daring plays to come down the pike in years but it was completely beiged by that monolithically tan, badly lit set.

Obviously, Nina Raine’s dark-edged comedy has some specific technical requirements. Surtitles are projected so hearing audience members can follow along when deaf characters converse in sign language. It’s an appropriately operatic conceit but there had to be a way to manage it without throwing up a tall, solid, oppressively khaki-colored wall that makes the space seem so shallow and the work feel so flat.

Tribes has deaf characters. It is not a “deaf” play. It is also a study, not a story, considering the many ways individuals and groups exchange information. We’re introduced to a smart, relentlessly combative, sometimes outright mean family of adults who are all occupying the same house for the first time since the children started leaving for college. The father (Barclay Roberts) is an academic and author of argumentative books. He’s learning Japanese, but he won’t insult his son’s intelligence by learning sign-language. The mother (Irene Crist) is writing a detective novel set around a dissolving marriage.

“I don’t know who’s done the murder yet. I’m going to decide at the end and then put all the clues in,” mother says, in one of the play’s more wantonly self-conscious moments.

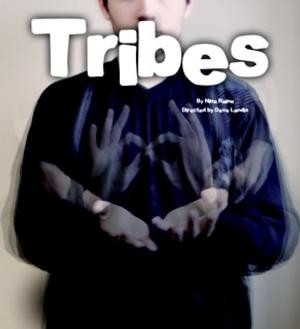

Nina Raine’s “Tribes” Maps the Boundary Between Listening and Hearing

The children are all struggling to define themselves outside the family. Daughter Ruth (Morgan Howard) is an aspiring opera singer piecing together a career performing in pubs. Only she’s been listening to herself lately, and that may not be a good thing. The oldest son, Daniel (Cameron Reeves), is a student writing his thesis about how language doesn’t determine meaning. He’s mentally ill and sometimes turns up the radio to drown out the voices he hears in his head. Billy’s the youngest. He’s been deaf from birth. He’s also an expert lip reader, raised by his opinionated father, to believe he’s no different than anybody else.

As one might imagine in a play called Tribes, conflict arises when an outsider enters the picture. Billy begins to interact with organized deaf culture and falls in love with Sylvia, who was born with normal hearing into a deaf family. She is also losing her hearing and descending into a silence that she describes as being much noisier than she ever could have imagined. Act one closes with the inevitable gladiatorial dinner party scene where she meets Billy’s family and is bloodied up from “hello.”

Odd, smug, and compulsively argumentative families are almost a cliche. We’ve seen this dynamic depicted countless times in stories by J.D. Salinger, in plays by Kaufman & Hart, and films by Wes Anderson. We’ve even seen it reflected in the macabre satire of The Addams Family. Raine’s sometimes jarring, immensely resonant script digs deep into this tradition, while venturing into new, exciting, and relatively uncharted territory. Circuit Playhouse’s finely acted production is never all it might be, but it’s never too far off the mark either.

I blame the beige.