If you were to zoom into a piece of metal — and I mean really zoom in, down to the atom, down to a billionth of a meter — you might get an image similar to those captured by Amir Hadadzadeh, whose microstructure images are now on display in his “Micro-Aesthetic” exhibition at the Art Museum of the University of Memphis.

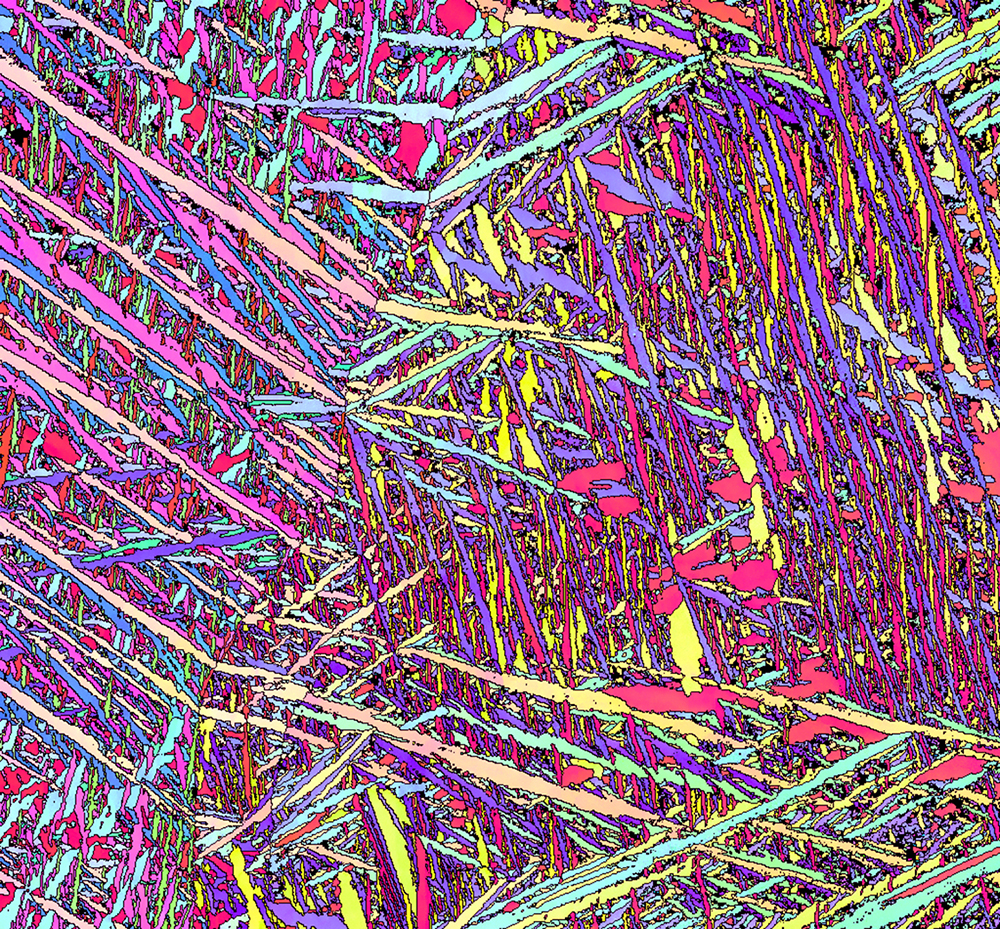

An assistant professor in the department of mechanical engineering, Hadadzadeh uses these images in his research on the nano- and micro-features of metals to evaluate the determining properties of the internal structures. “We find a connection between the properties and the features that we see on the very small-scale,” he says, “thinner than the thickness of a hair.”

While working with these images, taken through electron microscopy, Hadadzadeh realized that “whether I’m thinking about it or writing a scientific paper or trying to interpret all of the images, I have the same feeling as being high.” To him, this tiny science contained an unexpected beauty. “They are all scientific images,” he says, “but they have artistic features — colors, lines, patterns, and there’s similarity to what we see in our everyday life.”

So with the help of his wife, Sepideh Dashti, who is an artist working in both photography and performance art mediums, he selected a dozen or so images for his exhibition out of the hundreds stored on his computer from his time as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of New Brunswick and CanmetMATERIALS in Canada. “I tried to pick images with some features that can have a connection to our everyday life,” Hadadzadeh says. He even titled the images of the zoomed-in fabricated aluminum or titanium as objects they resemble — “Hot Peppers,” “Hairy Back,” “Horse Head,” “Atomic Heart.”

“My purpose here was to engage the general public with what I have been doing during my research,” Hadadzadeh says. While to the average onlooker the “hairs” on “Hairy Back” might be just that, engineers like Hadadzadeh use the hair-like lines to characterize the strength of the metal. Though the colors on some of the pieces may appear abstract, engineers use them to understand and interpret the image according to a color-coding system.

All of these features are important to Hadadzadeh’s research, but, he says, “I don’t expect the general public to understand the science.” In fact, he encourages visitors just to look around and enjoy what they see. “People can know that scientists are doing something that has scientific value and artistic value,” he says. “I’m trying to combine them here. This is the first step for me, and I’m trying to explore how I can do more and use the adventurous world of art to promote science and engage people and encourage them to learn a little more.”

Before this exhibit, Hadadzadeh had never really experimented with art. “I’m from Iran, and in Iran, usually families really would like their children to go to engineering schools or medical schools,” he says. “Unfortunately, at least for my generation, they didn’t appreciate art or humanities.” Even so, the professor found his passion in material sciences and engineering and can’t imagine doing anything else. “I’m not an artist,” he says. “I’m an engineer.”

But under his wife’s artistic influence, he’s learned to engage with his creative side. “Let’s be honest,” he says. “Engineers and scientists usually do not understand the art in the proper way. … She changed that mindset in me.”

Now that Hadadzadeh has had a taste of his wife’s creative philosophy, he plans to pursue his art further and hopes to have more exhibitions that can simultaneously promote art and science. “It is very helpful to have an artist in your life,” he says, “and I’m very grateful for it.”

“Micro-Aesthetic” is on view at the Art Museum of the University of Memphis until September 30th.