[This is the text of the speech I delivered at Shelby County Star Trek Day 2023. It is posted here at the request of the Memphis Trekkies in attendance, and with the indulgence of the Memphis Flyer.]

In some ways, all science fiction is about time travel. The basic trick of the sci-fi writer is to look around at the world, and image how it could be changed. At its simplest, that means changing one thing — usually, introducing some kind of new technology — and trying to figure out how that would change society. As the old saying goes, a good science fiction writer could have predicted the automobile, but a great science fiction writer would have predicted the traffic jam.

That means that science fiction is always looking to the future, which is what we all love about Star Trek. It’s the chance to have crazy adventures in space, but it’s also a chance to envision living in a world where all of the problems of our current world have been solved. These days, that’s more comforting than ever.

Usually, Star Trek is about being brave and going to new worlds. But on occasion, Trek has traveled into the past — or at least, “the past” from the point of view of the 24th century. Usually, when our space explorers become time travelers, the results are mixed. Star Trek: First Contact, for example, has its moments — I love James Cromwell’s drunken genius routine as Zefram Cochrane — but it’s not the best Trek that has ever been on the big screen. And as my friend Zack Parks said about Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, “It’s my favorite Trek, not the best Trek.”

But there are two time travel episodes, made 28 years apart, that are not only the best of Trek but some of the best television ever made.

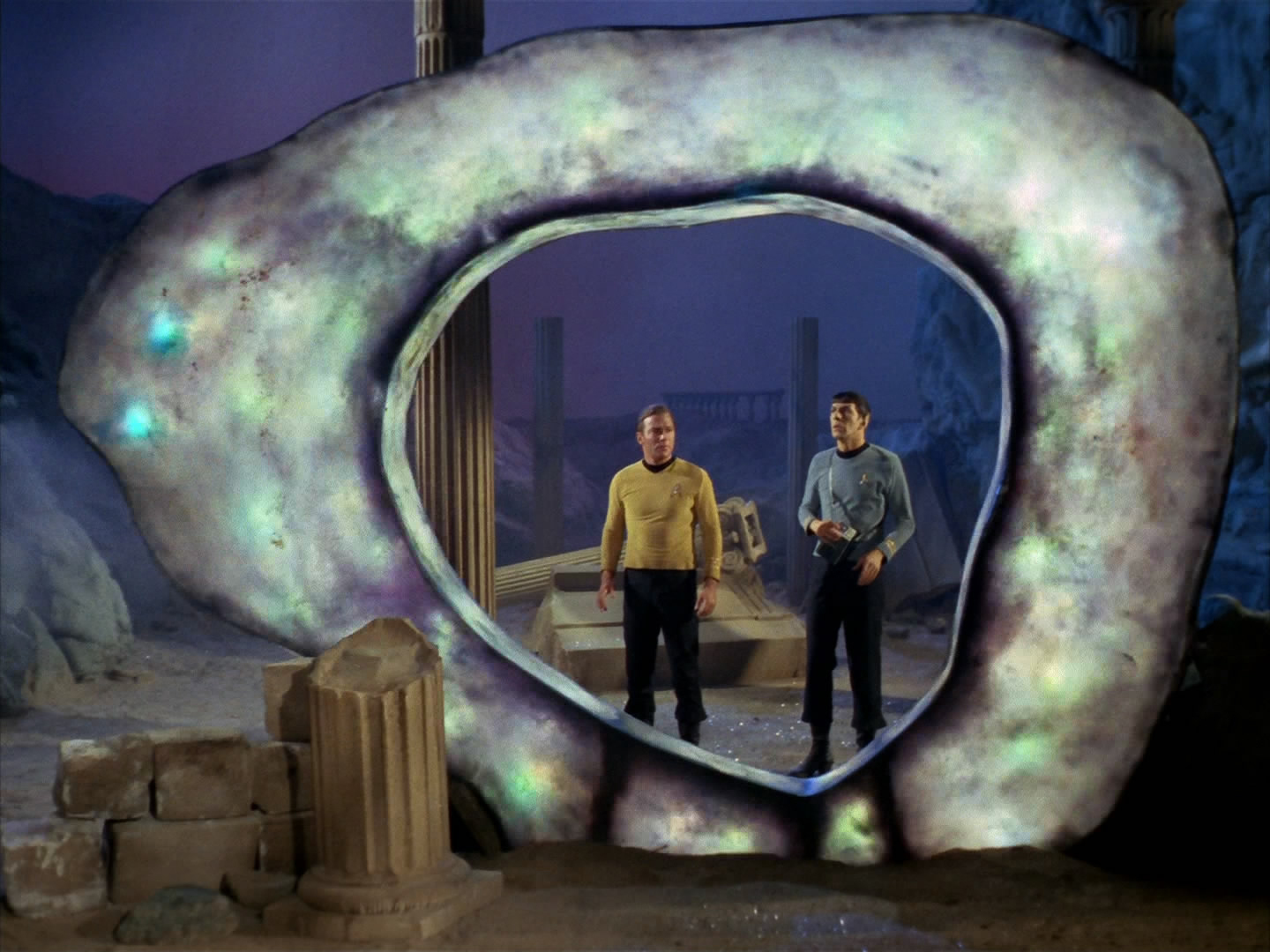

The first is “The City on the Edge of Forever,” which first aired on April 6, 1967. The episode was written by science fiction legend Harlan Ellison. The crew finds a time portal, the Guardian of Forever, created by a now-extinct advanced race. Doctor McCoy, who has been driven crazy by an accidental drug overdose, jumps through it and changes the timeline so that the Federation never developed.

Kirk and Spock follow McCoy back to the New York City of the 1930s. America is in the grips of the Great Depression. People are on the streets, desperate for work and food. Kirk and Spock stumble into a soup kitchen run by Edith Keeler, played memorably by Joan Collins. Keeler is a social reformer who preaches a message of compassion towards all and peace among the nations. Spock discovers that Keeler’s message will spark a social movement that spreads widely, and as a result when Nazi Germany invades Poland in 1939, the United States stays neutral. Pearl Harbor never happens, and the authoritarians win World War II because the newly pacifist nation won’t go to war to stop them.

But in our timeline, the one Star Trek was being produced in 1967, Edith Keeler died in an automobile accident before she could get her message of peace and universal love out. Kirk and Spock must then set the timeline right by allowing Keeler to die. The bad news is, not only is Keeler good to the point of saintliness, but Kirk has fallen in love with her. Now he must make a personal sacrifice to save the future.

Harlan Ellison was a notorious curmudgeon who hated what story editor D.C. Fontana and producer Gene L. Coon did to his script for “The City on the Edge of Forever.” Once, I met a writer who had been in the California sci-fi scene with Ellison. When I brought up Ellison’s temper, my writer friend vigorous defended him, saying Harlan was a prince of a guy who used his TV money to help out his fellow writers when they were down on their luck. My writer friend also told me the reason why Ellison was so mad at Trek. In the episode’s climactic scene, McCoy wakes from his delirium just in time to try to save Edith Keeler from the accident that is supposed to kill her. Kirk and Spock restrain him, and they watch her die. In Ellison’s script, it is McCoy and Spock who restrain Kirk. Even though the captain knows that saving her will destroy the future, he can’t bear to watch the woman he loves die. For a person in love, Ellison says, the needs of the one outweigh the needs of the many.

I can understand where Ellison is coming from. As it is, the episode ends much darker than most Trek episodes, with Shatner exclaiming, “Let’s get the hell out of here,” through gritted teeth. If Kirk knows he almost did the wrong thing, that he wanted to do the wrong thing, that line would hit a lot harder.

Sitting here in 2023, what’s interesting to me about “The City on the Edge of Forever” is its worldview. Pacifism is dangerous, it says. Not very Trek-like. But the worldview of Ellison and Gene Roddenberry in the late 1960s was that everything in the previous 30 years had pretty much worked out okay. World War II, with its enormous death toll and sacrifices on the population level, had been worth it. The belief that war was a necessary evil that helped to spur technological innovation was widespread in certain science fiction circles of the 1960s. Besides, the new liberal order of the West was ascendant, and people were freer and richer than they ever had been before.

At least, all the people that mattered. Three months after “The City on the Edge of Forever” aired, the Detroit Riots of 1967 began — also known as the “Detroit Rebellion.” It was the worst civil disturbance since the Civil War, with 43 dead, 1,100 injured, and entire neighborhoods burnt to the ground. The riots stared as a protest against police brutality stemming from a botched raid on a party where Black Vietnam veterans were celebrating their homecoming. The Black population of Detroit had long been the victims of housing discrimination, high unemployment, and systemic racism in general. People were fed up, and things spiraled out of control.

The Detroit Riots changed history. They sped up white flight from the city centers to the suburbs, influenced an entire generation of policing that came to view Black neighborhoods as potential powder kegs that must be kept down. After the riots that followed the King assassination the next year reinforced this view, the urban decline of the 1970s was inevitable.

Fast forward to January 1995. Deep Space Nine is in its third season and is really finding its legs. Episodes 11 and 12 are a two-parter called “Past Tense,” written by Ira Steven Behr and Robert Hewitt Wolfe. It’s a time travel episode that definitely carries a stamp of influence from “The City on the Edge of Forever,” and but it comes to some radically different conclusions.

The big difference with “Past Tense” is that it attempts to predict the future in a much more direct way than Trek usually goes about it. Sisko and the crew of the Defiant are summoned to Earth to address a Starfleet symposium. But a transporter accident sends Sisko, Bashir, and Dax back to the San Francisco of 2024. In 1995, that was 29 years in the future. It’s pretty much our now, so we can evaluate how well the writers did in predicting it.

The answer is: pretty darn well. In the fictional 2024, seafloor mining is just getting underway. That’s true today. There are student riots in France. That’s happening right now. The San Francisco Sisko, Bashir, and Dax materialize in what looks like a shopping mall — which is what gentrified cities like New York resemble today. San Francisco is the playground of tech moguls, like Chris Brynner, played by Jim Metzler, who is apparently an internet entrepreneur involved in something like social media. Society is polarized. There is a very comfortable upper class, which Dax manages to find her way into. Brynner rescues Dax, and she smoothly assimilates into the culture.

But there is also a huge lower class. The homeless, known as the “Gimmies,” and the mentally ill, known as the “Dims,” are herded into “Sanctuary Zones,” 20-block communities where the unwanted members of society are walled in to be forgotten. There’s a third group, the “Ghosts,” who are violent nihilists. Stuck in the past with no ID and no money, Sisko and Bashir are rounded up by private security contractors and thrown into a Sanctuary Zone. Welcome to the 21st century.

The vision of the future that 1995 Trek writers thought was bleak and dystopian came true in so many ways. The first thing that jumped out at me was that the police who were enforcing the separation between rich and poor were outfitted in paramilitary gear and appeared to be mostly private contractors. Yes, police carried guns in 1995, but it is still shocking to me to see police, or more often private security, dealing with civilians in full battle rattle. We shouldn’t get used to it.

Indeed, the evils of “getting used to it” is the theme of the episode. The people of fictional 2024 understand that this economic aparthied is deeply messed up. But they are all beaten down with hopelessness. One security contractor, played by journeyman character actor Dick Miller, freely admits that they’re milking the situation for overtime pay. A social worker tries to help, but she’s buried under the weight of the poverty and hopelessness.

Sisko looks at the calendar on the wall and sees that they have landed a few days before the Bell Riots, a pivotal event in American history that sounds an awful lot like the Detroit Rebellion. But history expert Sisko knows that this time, due to the existence of the “net,” everyday people were able to see the suffering of their fellow citizens and instituted change. The biggest thing the “rioters” ask for is the reinstatement of a federal jobs guarantee that sounds like FDR’s Works Progress Administration.

Keeping with Starfleet temporal protocols that have gotten way too much use over way too many years, Sisko and Bashir try not to influence events. But despite their efforts, Gabriel Bell, destined to become the hero of the riot, is killed prematurely, and Sisko must assume his identity. Bell’s heroism involved giving his life to protect hostages taken by a Ghost named BC, thus proving the basic humanity of the rioters to the general public. When the riots kick off— an event signaled by the explosion of a Molotov cocktail — the episode goes somewhere no Trek script has gone before. Shot on the Paramount backlot, it’s a gritty, violent scene of rioting which transitions into a hostage situation that looks more like The Taking of Pelham 123 or Dog Day Afternoon than The Voyage Home.

Michael Webb, a former white-collar, middle-class family man who landed in the Sanctuary Zone, says, “Why do they act so surprised? When you treat people like animals, you’re going to get bit.”

Starfleet officers are Trek’s paragons of morality. What do they do in this situation, which looks very familiar to us? The utopia of the 24th century cheats. They have access to infinite energy, in the form of matter/antimatter reactors, and can transform energy into matter at will. That means there is, for all practical purposes, no scarcity and no economic exploitation. So no one has to go hungry.

But Sisko, Bashir, and Dax’s words and actions suggest there is a deeper reason why the Federation is a utopia. The people there care about each other. Avery Brooks is on fire in this episode, and his finest moment comes when he lectures the cynical cop Dick Miller, “Caring is a start.”

Dax, who has ensconced herself in privilege, abandons it to help those in need. Bashir can’t stop himself from rendering aid to injured people, and his good deeds are rewarded. In the end, Dax convinces her friend Chris to use his internet channels to get the word out about the conditions in the camps. Sisko assumes Bell’s identity; once he’s sure things will play out the way they’re supposed to, he fakes his death, and the future is saved.

This was some seriously radical TV for 1995, and its vision has only sharpened in retrospect. To me, the most subversive moment of “Past Tense” comes at the very beginning, when Sisko is on a call with Quark and cites the 112th Rule of Acquisition: “Treat people in your debt like family — exploit them.”

In our 2023, it’s certain that a lack of empathy and apathy about how hopeless the prospects of change seem is at the heart of our problems. One need only look at the videos of Tyre Nichols’ murder at the hands of Memphis police to see where a complete lack of empathy can lead. From the liberal meccas of Los Angeles and San Francisco to the mean streets of Memphis, homeless people are more visible than ever, and tent cities that bear a resemblance to the Sanctuary Zones are everywhere. The 2020 Black Lives Matter protests called attention to systemic racism and police violence. Word did indeed spread through the internet, much as it had during the Arab Spring and the Occupy Wall Street protests, and minds were changed.

But today, on the eve of Trek’s Bell Riots, progress seems precarious. One political answer to misery and the failure of the economic system that we see around us is to make our system more empathetic and responsive to the material needs of all of the people. Another political solution is for the economic elites to tighten their grip further into fascism. A regime willing to murder its populations wholesale — or to let them die from neglect, famine, and disease — uses the occasional riot as an excuse for more repression. It’s also worth noting that the way the writers resolved “Past Tense” was to persuade a tech billionaire to help use his social media assets to spread the world of social justice. Elon Musk just massively overpaid for Twitter in order to better control what messages break through. It’s a conceit of American movies and television, up to and including The West Wing and Star Trek, that once the word gets out, the people will do the right thing. As we have seen in real life, this is not always the case. But I’m a Trekkie, so I always remain optimistic.