The current exhibition at the Dixon’s Mallory and Wurtzburger

Galleries, titled simply “Beth Edwards,” is the most complete gathering

to date of Edwards’ emotionally complex portraits of the

mid-20th-century American dream of owning shiny new convertibles and

ranch-style homes furnished with Danish modern divans, potted plants,

and modern artworks, or, if original work was out of the question, good

reproductions.

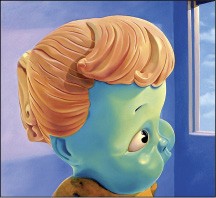

Instead of human models, Edwards uses vintage rubber toys as

stand-ins for the proud homeowners. In Happy Day, an

anthropomorphic mouse with a frozen smile and huge lidless eyes stands

proudly in his spic and span living room. The shape of his moist black

nose is repeated in the fractured face of Picasso’s portrait of his

mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter. In Good Morning,

another happy homeowner — in this case, a beautiful, young golden

retriever — is backdropped by a royal-blue divan and Philip

Guston’s painting of a huge pile of worn-out footwear (horses and

humans), an allusion perhaps to the labor required to build beautiful

homes for the well-heeled.

Pinkney Herbert’s Delta Series L

The glossy surfaces, controversial masterworks (that elicited

outrage when they were first unveiled), and the frozen-faced dolls that

populate Edwards’ “happy paintings” suggest the search for happiness is

a slippery slope layered with complex feelings that can exhilarate or

undo us.

Like Edward Hopper, Edwards handles color with such mastery that her

artwork achieves a kind of transcendence. The iridescent-green baby

doll in Annunciation looks out a window at a blue sky feathered

with clouds. The figure’s chubby cheeks and huge brow are framed inside

a Hopperesque square of lavender light.

Ultimately, Edwards’ art is about the power of light to consume all

color and form, to absorb all paradox and pain into visions of

paradise. Edwards understands Hopper’s desire to do nothing but paint

light on the side of a house.

Through September 6th

Pinkney Herbert’s Jig

In David Lusk Gallery’s current show, “Floating World,” Pinkney

Herbert’s paintings no longer blast our point of view across

30-square-foot surfaces. Neither are they as spare as the paintings in

Herbert’s 2007 exhibition, a show in which softly curving lines,

wide-open spaces, and the quiet authority of works like Wing

seem inspired as much by Zen Buddhism as 20th-century

abstraction.

Instead, Herbert’s “Floating World” works are by turns fluid,

syncopated, celebratory. Their open and buoyant compositions, inspired

in part by the elegant woodblock prints of Japan’s Edo period

(1603-1868), invite us to take our time, to explore their textures,

colors, and shapes, and to realize that, though they are more subdued

than Herbert’s explosive earlier work, these paintings are as evocative

and original as any in his long and varied career.

Beth Edwards’ Annunciation

In “Floating World,” we feel the rhythms of New York as well as

Memphis, the two cities where Herbert lives and paints. Deep-red spiked

flowers surrounded by scumbled umber at the heart of Herbert’s pastel

on paper Delta Series L look as rich as Mississippi bottomlands,

as fertile as the Southern soul. In Buoy, a figure eight

accented with red-and-yellow lozenges wafts on air currents that twist

in unexpected directions like New York City’s improvisational jazz.

A cartoon-like hand with triple-jointed fingers and attenuated wrist

lies at the center of the nearly 6-foot-tall painting Jig. We

can almost hear the sound of one hand clapping in this crisp-edged,

bright-orange shape backdropped by a wash of pure yellow.

Two years after his last show, Herbert returns to David Lusk with

his sense of humor intact, with a new zest for life, with a mindset

similar to what 17th-century Japanese novelist Asi Ryoi described in

Tales of the Floating World as “refusing to be disheartened,”

turning one’s attention to the pleasures of the beautiful, impermanent

world.