It was a dark day in 1989 for Memphis music fans when word got out that the old Stax Records building on McLemore, then owned by the Southside Church of God in Christ, was slated to be demolished. It had been in disrepair for some time, unused since the company’s 1975 involuntary bankruptcy, with crumpled PR photos and odd reels of tape scattered in the debris, languishing in limbo between the hopeful past and an uncertain future. Ironically, Stax fans had only seemed to multiply in the meantime. On this day, those in Memphis worked their landline phones, alerting others to a protest that was brewing.

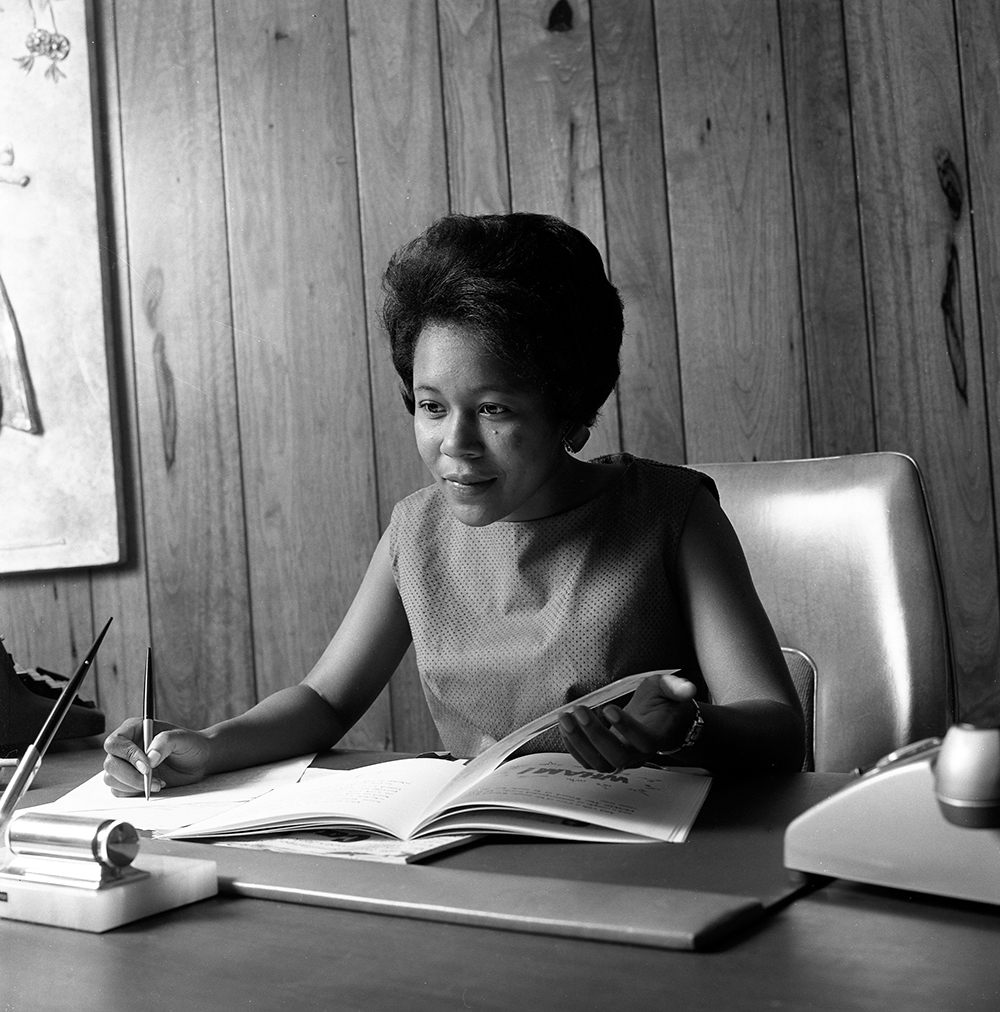

Deanie Parker, who had headed artist relations and publicity at Stax before it was forced to close, was in on that phone tree, but she was not having it. “I started getting phone calls from people who knew me, and they said, ‘We’re getting ready to protest the razing of the Stax building!’ And I said, ‘Okay.’ And they asked, ‘Are you going to join us, are you coming?’ And my attitude was, ‘What good is it going to do? Why are we trying to save a run-down building that was already run-down when we converted the theater into a studio? Who in the hell is in the building? Is it doing any good? Are they cutting any records there? Are they providing jobs for anybody? What the hell — let ’em tear it down!’ And I felt badly after I had done that because I understood their passion, and I knew what they were trying to do. But this was deeper for me. What was that raggedy-ass building going to do? It wasn’t going to bring Stax back.”

Parker, as it turned out, was playing the long game. She knew better than anybody that Stax’s magic wasn’t in the building’s walls, but in the people who walked its halls. Now, nearly three and a half decades after the original building bit the dust, those faithfully reconstructed walls are celebrating their 20th year of being peopled again, animated by the same spirit that made Stax unique in the first place. On the eve of a 20th anniversary gala on April 29th, Parker notes that the creation of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music benefited from “the things that happen when people are working together. Allowing their creativity to take over, in the spirit of cooperation.”

Or, as executive director Jeff Kollath says of the Stax Museum now, “This is such a people-driven endeavor. And this is a Memphis people-driven endeavor.”

The Birth of the Soulsville Foundation

The campus built around the Soulsville Foundation, under which the museum, the Stax Music Academy, and the Soulsville Charter School operate, is striking in just how closely it resembles Parker’s original vision. Called to protest the building’s demolition or to invest in a Stax-themed nightclub on Beale Street, Parker instead asked, “What’s wrong with a museum and a companion school of some sort, an academy or a performing arts center?” She recalls telling other parties, “I’d like for people to study and preserve and promote what we did. And pass it on, with an educational component and a museum that people could come and see.”

By the early ’90s, the working group sharing Parker’s vision called itself CISUM, reverse-spelling the word at the center of it all, having architectural renderings made and securing a license to use the Stax name for some 20 years. Nothing came of that, but by the decade’s end, Sherman Willmott of Shangri-La Records had started a new nonprofit, Ewarton, using letters from the names of Stax’s co-founders, Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton, that had not been used when “Stax” was coined.

After years of false starts, Parker recalls, “What I said to them was, ‘It’s about doing the right thing, and it’s about damn time! So count me in.’ And that was where we started. Sherman and I worked together, and he was busy procuring artifacts from everywhere and anywhere. And a curator, he was not! But nevertheless, he had the passion and the vision and he was making hay while the sun was shining.”

And, Parker’s lack of interest in the old building notwithstanding, the original lot on McLemore Avenue was a prime concern. “We felt very strongly that success rested on us getting the original site back. There’s something spiritual about that place, I’m telling you. It wasn’t in that raggedy building. It was a sense of place. A sense of place.”

Soul Comes Home

That in turn led to a change in priorities. “We were driven by building the Stax Museum of American Soul Music. But then I became reaquainted with that community and realized how that area had decayed after Stax was closed. That area had deteriorated beyond recognition. People didn’t give a damn because they felt that they had been thrown away and that nobody cared. So it was good that the board decided to switch horses, and you know what we finished and cut the ribbon on first? The Stax Music Academy. That was opened a year before the museum.”

Meanwhile, as Ewarton became the Soulsville Foundation, seeing a new museum facility take shape according to the blueprints of Stax Records’ original home was emotional for many. “Every day until that museum was opened, I walked from the front door to the back door of that place,” says Parker, “and the day that I walked through there and didn’t cry, I knew we had achieved what we were trying to do. By that time I was too tired; I was all cried out! It was an emotional thing, seeing it come alive.”

True to the Stax spirit, that also meant reuniting the people who’d made the label what it was. As befitting a people-driven enterprise, Parker was the ideal recruiter. “One of my responsibilities at Stax Records had been artist relations. And as the publicist, I was acquainted with all of them in some way. I was connected,” she says. But she found that it wasn’t as straightforward as she’d hoped. “I focused on galvanizing the Stax family. But I got mixed responses. Some of us left there bitter. People who were essentially told to go to hell, with nobody ever saying, ‘Thank you.’ Some of us left there with all kinds of damn baggage — baggage that I’m still finding out about today.”

Nonetheless, most of them were moved by the finished space. Touring the museum with his extended family, bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn enthused that everything looked the same but now had air conditioning (the original space had none). “After it opened, Eddie Floyd told me, ‘I went through there 12 times.’ They were ecstatic,” says Parker. “It was tangible evidence of Memphians finally celebrating what we thought was great and wonderful.” The greatest celebration was not the ribbon cutting on May 2, 2003, but the concert at the Orpheum Theatre anticipating it. Dubbed Soul Comes Home, the Stax and Memphis music reunion concert (featured on this week’s cover) included Isaac Hayes, Booker T. & the MGs, Mavis Staples, the Rance Allen Group, Jean Knight, Eddie Floyd, William Bell, Carla Thomas, Ann Peebles, Al Green, Jimmie Vaughan, and other luminaries.

Back to the Future

Now, 20 years later, it’s impossible to imagine the Soulsville neighborhood without the Stax Museum of American Soul Music, the Stax Music Academy, or the Soulsville Charter School. The museum alone has hosted enough art exhibits, book discussions, and music events to keep it at the forefront of ever-evolving scholarship on American soul music. But over time, the exhibits themselves have not evolved much — until now.

The 20-year mark has inspired some long-overdue makeovers to the museum this year. As Jeff Kollath points out, “The public isn’t really aware how much our collection has grown in the last five to 10 years. We see it because our shelves are full, and we’re always connecting with new objects and new materials in the archives. [Collections manager/archivist] Leila Hamdan is doing a lot of organizing and getting a better handle on some of our documents.”

Now some of that will see the light of day, but, Kollath stresses, “This isn’t an expansion. We’re prettying the place up and changing some things out for the first time in 20 years. And we’ll have a rolling, gradual opening of new exhibits. We’ll be correcting errors, especially where they have birth and death dates. Some things have aged out. And we’ll include more Memphis history: how Stax sprang up in this city, and what about this city made that happen? The big thing is relating the end of Stax Records as accurately and as engagingly as possible. Currently, the end of Stax is on three oval panels with no photographs; it’s a book on a wall. And it’s not totally accurate, either. People want to say Stax was dead, but it never really died. Obviously we’re the legacy of that.”

Retelling the story of Stax Records’ latter days will also include a heightened focus on the political activism of the era. “We started looking at that side of Stax Records in 2018 with the ‘Give a Damn’ exhibition we did at Crosstown Arts,” says Kollath. “That was built around activism at Stax. Artists felt more compelled to speak out, to act, and became more involved in the community here in Memphis, and in the case of Isaac Hayes becoming internationally involved in charitable pursuits. That peaked with future presidential candidate Jesse Jackson acting as Isaac Hayes’ hype man at the WattStax festival. There’s all these reminders of the cultural and political impact of Stax that I don’t think are addressed enough.” Look for more of that, not to mention Rufus Thomas’ blazing-hot pink hot pants, as this anniversary year progresses.

The Night Train and the Church

Having duly recognized the sociopolitical impact of Stax, it should be noted that the prevailing mood at the Soulsville Foundation these days is more in line with those hot pants: “Let’s party!” This museum does not take the launch of its third decade lightly, and from 7 p.m. till midnight on April 29th, its walls will witness some serious celebrations. As Soulsville Foundation president and CEO Pat Mitchell Worley says, “The party itself is a trip through Black music. That’s why we call it the Night Train Gala. It reflects how important the train has been historically for African Americans, as far as travel, especially in the South. It’s how the Chicago Defender was delivered to the South, when Pullman porters would give copies of the Defender to people who wanted news that was important to African Americans. The trains went through the South and then up North, mirroring the map of how music was moving.”

Such an implied journey, complete with signature drinks and Pullman porters in each room, will underscore the degree to which the Stax Museum is indeed representative of all American soul music, as party patrons move through different stages in the evolution of Black music. “We’re owning that we’re the global capital of soul,” says Mitchell Worley. “The event will start with Shardé Thomas’ Rising Stars Fife & Drum Band to give that nod to Mississippi, and then we’ll move to jazz with Joyce Cobb and then on to a capella doo-wop. Then we’ll come to the sweet soul music, with our Stax Music Academy Alumni Band performing with special guests. A couple of Stax artists will jump up for a song or two. That’s going to be fun! From there we’ll go into hip-hop ciphering and spoken word, in recognition of those styles’ place in the story of African Americans. It’s an important piece because from the ciphering came rap. So we’ll end with the hip-hop piece and a multiple DJ battle focused on all the Stax songs that have been sampled. It’ll be interactive, so if people know the song that was sampled, they can go put it up on the board. Sort of like the Soul Train board!”

Yet as the party righteously rages on, patrons would do well to remember the quiet, beating heart at the center of the Soulsville Foundation, embodied in the first thing that most patrons see when entering the museum: a little country church, fully reconstructed, that represents both Stax’s musical roots and its people-centered mission. In this case, it’s a direct expression of Deanie Parker’s people. “My grandparents were buried on a lot at Hooper’s Chapel A.M.E. Church in Duncan, Mississippi,” she says. “It was the first church I ever attended in my life. One weekend when I took my mother down, over 20 years ago, she looked at the church and said, ‘I’m afraid that one day lightning is going to strike this church, and I don’t know if I could bear to see it burn. I’d almost rather tear it down.’ And I thought to myself, ‘What a wonderful opportunity it could be if we could dismantle this church, move it to Memphis, reassemble it so that it would fit into that Stax museum, and serve as a means of helping people appreciate the roots of soul music.’”

That church still stands in the heart of Soulsville today, much as Parker’s original dream stands in the form of the museum, the music academy, and the charter school. “Those three programs are dynamic and make the Soulsville campus and foundation distinctly different from any other in the world,” she says with more than a little pride. “Because we’re doing exactly what I dreamt we should do the first time I had an opportunity to communicate my vision: to showcase and preserve the incredible contributions of Stax Records, and to pass on and teach that style of music. And most importantly, we’re doing something for the children.”