Double Date,” at Marshall Arts, is an exhibition mounted by partners who are passionate about art and each other.

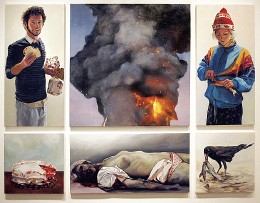

Clare Torina’s funny and fierce painting, Fodder, filters 16th-century religious fervor through 21st-century sensibilities. Like Matthias Grünewald’s masterpiece, The Isenheim Altarpiece, Fodder pays homage to life/death/regeneration, but, as the title suggests, Torina’s emphasis is on natural processes. Instead of Christ entombed, Torina acknowledges her own demise by painting a cadaver at the bottom of her multipanel work with the same white-blond hair, pear-shaped face, and svelte body as her own. Sebastian and Anthony, the saints who flank Christ in Grünewald’s painting, are replaced with portraits of Torina and her husband Steven Almond, painted with such convincing nuance they look alive.

Elizabeth Owen’s colored pencil portraits explode with energy. Waves of blue satin billow around bare legs, foreshortened toes nearly touch the face of the viewer, and bright-pink underwear, candy-cane striped socks, and ruffled dresses fill the paperwork Panties with a kaleidoscope of color and movement.

Owen’s husband, sculptor Tim Kinard, is well-known for his savvy, sassy statements about relationships. Kinard delivers one of his wryest works yet with Up and Down, Round and Round, an installation consisting of a doe and a bear-like creature, escapees from a merry-go-round with carousel poles still implanted in their bodies. The bear’s pole looks phallic; the young deer looks pierced with a hunter’s spear and her posture — head lowered, flanks held high — can be read as submission or prelude to flight.

Somewhere between bear and Bigfoot, this creature is beginning to ask the big questions — about meaning, about purpose — and, like the rest of us, looks a bit baffled by life.

Clare Torina’s Fodder: part of ‘Double Date’ at Marshall Arts

Steven Almond’s stop-animation video Two in the Trunk starts out with a breakfast of pancakes, escalates into a fork-fight to the death, pauses for a moment of angelic intervention, and ends with an act of cannibalism so frenzied and primal that viewers play and replay the video in order to digest (pun intended) the final scene. Almond’s four minutes of mayhem, played out by characters fashioned from eyeglasses stuck into feet of clay, is an unsettlingly funny reminder of the tenuous nature of a “civil” society, whose members are evolutionary patchworks of intellect and instinct.

Through February 16th

For his exhibition “Stills: Photographic Paintings & Sculpture,” Jonathan Postal mounts brutally beautiful syntheses of noir, fantasy, and reality on the brick walls of Automatic Slim’s. The vintage televisions that frame several of Postal’s photographic paintings are nostalgic, but they are unnecessary props for already powerful works of art in which members of car clubs, camera clubs, and nightclubs “play” part-time at being tough and sexy.

One of Postal’s most powerful pieces, Fallen Angel, combines photography’s shades of gray with the golden-whites of acrylic glazes. A bargain-basement chandelier casts a soft glow across an old mansion’s paneled walls and highlights the blond hair and porcelain thin body of a girl. The blurred white wings spread across the center of the painting suggest the angel has just completed her fall. Postal’s descent into hell is also the swan song of a girl too inexperienced to extricate herself from a diet of drugs and casual sex.

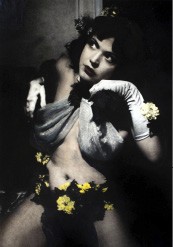

Outside the Hi-Tone Café in the late 1990s when countercultures flourished, Postal shot Memphis Confidential, an image of a young woman with artificial flowers pinned to her long white gloves and a black feather boa draped around her shoulders and thighs. Like Postal, this woman is a savvy local artist (and a sometime burlesque dancer) who knows how to mix the classy with sensuality and kitsch, how to dive into life without drowning.

Through February 28th

Jonathan Postal’s Memphis Confidential