For more than a quarter-century now, Pete Rose has been a one-man barstool debate. Does the man with the most hits in baseball history deserve a plaque in the Baseball Hall of Fame despite partaking in serial gambling in the late 1980s as manager of the Cincinnati Reds? It’s a divisive subject, and has only grown more complicated with the recent news (first reported by ESPN) that Rose actually placed bets as a player late in his career with the Reds. (Rose was baseball’s last player/manager, serving both roles with Cincinnati from 1984 through the 1986 season.)

The famous Dowd Report originally led to Rose’s ban from the game — and with it, consideration for the Hall of Fame — in 1989. Baseball’s commissioner at the time — A. Bartlett Giamatti — dropped dead of a heart attack eight days after Rose signed an agreement accepting the lifetime ban. (Don’t connect the two events. Giamatti smoked like a chimney.) Rose got very little sympathy from Giamatti’s successors in the commissioner’s office, first Fay Vincent then, for the longest time, Bud Selig. MLB’s new sheriff, Rob Manfred, is allowing Rose to participate at next week’s All-Star Game in Cincinnati, though the recent allegations will make any Rose appearance positively cringe-inducing for those of us who care about the game. And for those who still care about Peter Edward Rose.

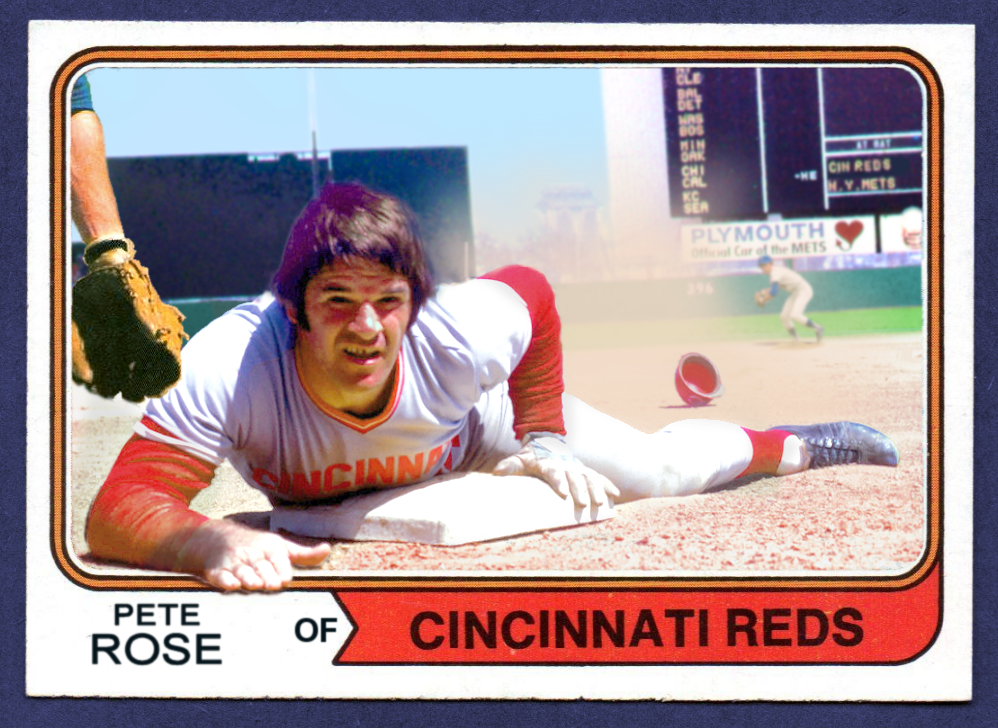

There are really two debates to the ongoing Rose saga. The first, and most direct component of his lifetime suspension is the exclusion of Rose from any job affiliated with Major League Baseball: manager, coach, front-office executive, pitch man, etc. The second component, of course, is the one most debated on that barstool: exclusion from consideration for the Hall of Fame. (And let’s get over the “consideration” part. With 4,256 hits, three World Series rings, and the sport’s greatest nickname of all-time — Charlie Hustle — Rose would be a lock for induction on his baseball merits alone.)

Maybe it’s time we start considering the two components separately. Gambling is baseball’s unpardonable sin, going back (at least) to the infamous Black Sox scandal of 1919, when eight Chicago White Sox players — including the great Shoeless Joe Jackson — were found guilty of throwing the World Series. Signs are posted in every clubhouse, warning team personnel against betting on a Major League Baseball game. And Rose is not the first legend to feel the gravity of this offense. There was a time Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays — the Mick and the Say Hey Kid! — were pariahs merely for their associations with casinos, and this was after their playing days. If Rose bet on his Reds, particularly as a player, he should not be allowed to work for an MLB team in any capacity.

Then there’s the matter of the Hall of Fame. It’s important that induction in the Cooperstown shrine is reserved for baseball’s absolute elite, that such selection is taken very seriously (thus the five-year waiting period after players retire before they can be added to the ballot). But I’ve come to believe we shouldn’t take the Baseball Hall of Fame quite as seriously as we have in the matter of Pete Rose. It’s a baseball museum, a bricks-and-mortar history lesson on the American pastime. It is not passage to sainthood for the enshrined. For such a facility to exist without acknowledging Pete Rose’s extraordinary career cheats the lessons it was built to provide.

So give Pete Rose his Hall of Fame plaque. Make sure the plaque includes language describing his lifetime ban. Maybe Rose is denied an induction speech if the Hall of Fame (most importantly, its living members) feels further punishment is necessary. Do this while the man is alive. In the final analysis, Pete Rose has been very bad to himself. I’m of a mind that Rose, as a player, was historically good for the game.