“Help me, Merle,

I’m breakin’ out in a Nashville rash

It’s a-looking like I’m fallin’ in the cracks,

I’m too country now

for country, just like

Johnny Cash”

— Dale Watson,

“Nashville Rash”

In March 1998, after winning the Grammy for Best Country Album — with little support from the Nashville music establishment, and even less airplay on mainstream country radio — Johnny Cash and his producer, Rick Rubin, took out a full-page ad in Billboard magazine “to acknowledge the Nashville music establishment and country radio” for their “support.” The infamous thank you advert was constructed around a picture of Cash from his 1970 concert at San Quentin State Prison. Cash’s snarling face was twisted up like the mean-eyed cat he’d sung about back in ’55, and his defiant middle finger dominated the foreground.

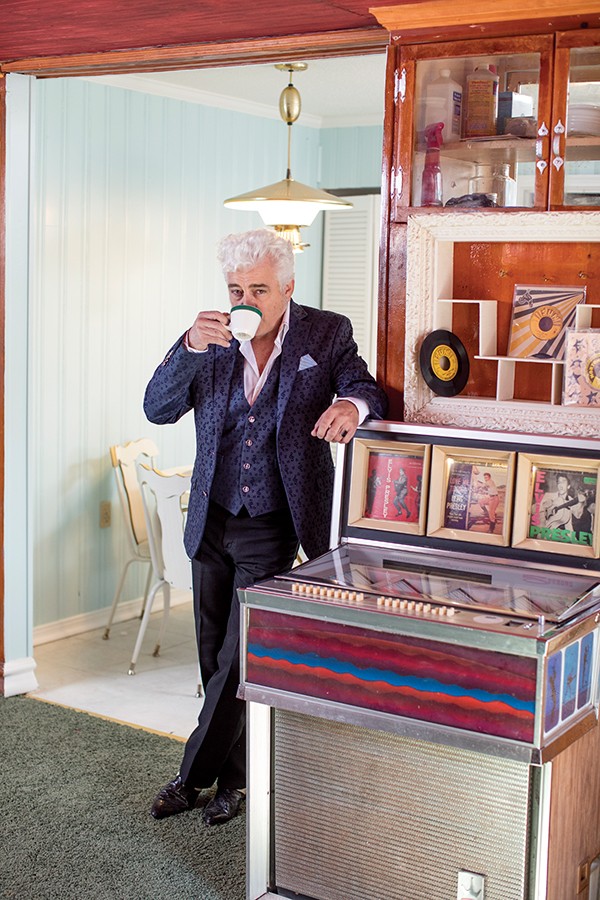

Dale Watson

Three years earlier, on his 1995 debut album, Cheatin’ Heart Attack, Dale Watson, an independent-minded Texas songwriter cut from the same fabric as Texas crooner Ray Price and West Coast songster Merle Haggard, predicted this precise moment in music history. And he provided a reasonably accurate summary of his own future career trajectory, in the opening line of a song titled “Nashville Rash.”

“I’m too country now for country, just like Johnny Cash,” he wailed. For Watson, who’d been honing his skills in Texas bars and dancehalls since he was a teenager, “Nashville Rash” marked the start of a decades-long beef with Music City, U.S.A. and the beginning of a honky tonk hero’s journey that’s taken him around the world, and brought him, at last, to Memphis, where he’s putting down roots.

“Yep, I’m about a mile away from Graceland,” Watson says, taking a lot of pride in his new Whitehaven neighborhood. “It’s great,” he says.

Watson, whom the Austin Chronicle has described as one of the biggest artists in Texas country (let that sink in), coined the term “Ameripolitan” when the genre’s modern and traditional forms grew so far apart they no longer resembled one another, and older terms like “alt-country” stopped making sense as a descriptor. He wanted to rebrand and raise the profile of contemporary music with deep, identifiable roots in living forms — western swing, honky tonk, rockabilly, and outlaw country — that have no place in today’s Nashville pop. Watson created the Ameripolitan Music Awards in 2013 to recognize working artists as sonically diverse as vampire outlaw Unknown Hinson, Tex-Mex rocker Rosie Flores, and lonesome troubadour Wayne “the Train” Hancock, while paying tribute to living legends such as country rock pioneer Wanda Jackson and honky tonk hit machine, Charley Pride.

When Watson moved to Memphis from his longtime home in Austin, he brought the Ameripolitan Music Awards with him. It’s a small movement compared to Nashville’s Country Industrial Complex, but the move to Tennessee’s musically significant second city might still be viewed as a big middle finger to the country capital. Maybe the biggest since Cash won his Grammy.

Watson’s Ameripolitan Music Awards found a new home in Memphis.

“It’s true,” Watson says with a belly laugh. “The reason Ameripolitan fits so good here is because, since the beginning, Memphis has always been the rebel kid of music. From Elvis and Jerry Lee and the honky tonk side of Johnny Cash, the music that grew here grew the same way the outlaw music in Austin grew there. Because it was fertile ground, and it wasn’t repressed. I’m not bad-mouthing Nashville; that’s just a fact.”

“Where’s your conscience, what’s the problem

Speak up and say what’s wrong …

Mr. DJ, could you please play a real country song.”

— Dale Watson, “Real Country Song”

On Saturday, February 11th, at a music showcase for Ameripolitan 2018, Watson strolled onto stage at Graceland’s new theater at The Guest House wearing clothes from Lansky Bros. and holding a can of Wiseacre Beer. If Charlie Rich was the Silver Fox, Watson’s a White Wolf, with his snowy, exploded pompadour and bushy sideburns that dip well below the jawline. Before introducing Western Swing revivalists the Farmer & Adele, he launches into a familiar routine about his abiding love for Lone Star Beer, a Texas staple Watson and his band the Lone Stars have described in their shows as “the best beer in the world.”

“But we’re in Memphis,” Watson drawls, pointing to his colorful can and grinning for a crowd of grown men dressed up like cowboys and tattooed ladies in vintage dresses. “Wiseacre.”

Watson’s love affair with Memphis isn’t new. He’s been a regular visitor for 30 years, booking shows at the Hi-Tone, Murphy’s, and Blues City Cafe, and recording at Sun Studio, whenever he got the chance. He recorded a complete Christmas record at Sun in 2000, in addition to a pair of LPs called Sun Sessions and Dalevis.

Dale Watson (above) plays the Blues City Cafe.

“Something about that room is so magical,” Watson told the Flyer in a 2013 interview. “A lot of it’s because of Elvis being there, of course. But even more so, it’s because the sound you get in that room is like nowhere else. It’s just amazing.”

Whenever a new band member joined the Lone Stars, Watson — who nearly graduated from truck driving school, has put out three records full of classic trucking songs, and very often pilots his own tour bus — would drive miles out of the way to take the newbie on a tour of Graceland.

In fact, what began as a quest to find an Airbnb on a road trip to Nashville evolved into a hunt for an investment property in Memphis. “I thought maybe if I had a place here, I could come more often,” Watson explains, while hanging leopard-print fabric on the ceiling of his personal jungle room, complete with a tiki bar and a jukebox full of Sun records. “So I looked around for houses in the area, and I thought, ‘I want to move.’ Everything about Memphis was electrifying to me. I’ve always loved the city and its history. But having a place was never sustainable for me. Now I’ve been doing this for a long time, and I’m at a point in my career where I can live anywhere I want to live. And once I came down here and looked at the houses and the scene, I said, ‘I’m going to put down roots here.'”

Putting down roots anywhere is difficult for musicians who make their living on the road playing up to 300 dates a year.

“That’s true,” Watson says. “And it’s why having this place is so important to me. When I come home, like anybody, I need to get energized. Austin, which has been my home for over 25 years, has grown so much, and a lot of the personality of the town has changed. There are condos built over the old beer joints where I used to play.”

“Our loss is definitely your gain,” says Whitney Rose, a Canadian-born singer/songwriter who grew up in her grandparents tavern, where she fell in love with American country music. She visited Austin to play a two-month residency at the Continental Club in 2015 and never left. Rose, who came to Memphis to perform after being nominated for an Ameripolitan Award in the Best Honky Tonk Female category, says Watson embraced her music right away, helped her discover Austin and find more opportunities for work. “He’s so generous,” she says.

“I’m so grateful for communities like the Ameripolitan community because it gives artists like me a home,” Rose says. “I’m not in this for the money or the commercial radio play. It’s not what’s trending or cool. Music has to progress, but the bones have to be there, too.”

The “bones” Rose describes are evident on her 2017 South Texas Suite EP. Recorded at Watson’s Ameripolitan Studio in Austin, it marries her Tom T. Hall-esqe gift for storytelling with an affinity for Texas dancehall song-craft.

Watson only has one rule in his band: Have fun. That directive seems to spill over into his approach to both putting together musical festivals and interior decorating. In addition to his Graceland-inspired jungle room, Watson’s Memphis home improvements include transforming another room into the bedroom set from the classic 1950s TV comedy I Love Lucy. His mid-century house has been given a radical mid-century makeover to match the airstream-style trailers he keeps out back and his ’58 Edsel and ’57 Ford Fairlane. Watson’s customizing the living spaces to suit his own eccentric taste, but hopes to Airbnb two of the rooms in his house while on the road.

“Just a mile from Graceland,” he repeats, selling the concept as effortlessly as he sells his songs.

Tell ’em stick it up high,

Where the sun don’t shine.

Get pissed, an’ get mad,

Tell ’em that’s country, my ass.

— Dale Watson, “Country My Ass”

By the time you read this story, the Ameripolitan Awards, 2018, which, in addition to the ceremony, included four talent-packed music showcases featuring dozens of performers and a fashion show, will have come and gone. The prizes, including a Legend Award for Sun Studio founder Sam Phillips, were handed out at about the same time these pages were rolling across the press. You can check the Flyer‘s website to see results and catch some highlights from a show with appearances by artists like Sleepy LaBeef, Rev. Horton Heat, Big Sandy, Dicky Lee, and Matthew and Gunnar Nelson.

This year’s big Ameripolitan event may be in the books, with more fans satisfied and more converts won, but for Watson and like-minded artists, the bigger question remains: How do you convince people that genre music can be vital and not stuck in the past.

“You can build a new house with an old hammer,” Watson says, revealing an unlikely inspiration for the Ameripolitan concept — John Lennon. “When he was asked about the Beatles’ early influences — like the Crickets and Buddy Holly — he said something like, ‘Yeah, we used to do that stuff, but we were unable to imitate our influences. And in that inability, that’s where our originality lies.’

“That’s what we do,” Watson says.

Of course, the trick is always to get more people to sample the product, and Watson’s answer to that mirrors his own work ethic: Take it on the road. He sometimes imagines the Ameripolitan brand as a tour, in the spirit of the Grand Ole Opry’s traveling shows, where established stars like Ernest Tubb and Hank Snow would headline package events showcasing half-a-dozen emerging artists. He thinks the awards may have to move on to seed other cities for a year or two, as the concept works its way into the nation’s consciousness.

“But I think it’s going to be in Memphis for at least the next year or two,” Watson says. “The hard part is that so much of this gets done from the road. It helps to have friends who can help, and I’ve just got a whole lot of good friends in Memphis.”

The last showcase before Tuesday Night’s Ameripolitan awards ceremony was held at Blues City Cafe, and the band box was packed to the edge of discomfort. Watson played this showcase himself, as did Rose and others. On stage, members of the Greenline Travelers, a throwback string band from Stockholm, Sweden, admitted to feeling a little pressure playing their set list in a city famous for its music. Then fiddles began to saw and the band launched into a pitch-perfect rendition of Ray Price’s “Please Release Me.” Ja!

Memphis’ branded reputation as the home of the blues and birthplace of rock-and-roll sometimes obscures the fact that, in its infancy, rockabilly was alt-country, and from the Wilburn Brothers, Charlie Rich, and Chips Moman to the Louvin Brothers, who worked as postal clerks in Memphis before recording their hits elsewhere, the Bluff City has a deep country past. With an authentic force of nature like Dale Watson putting down roots “just a mile from Graceland,” it may also have a country present and future.