For years, decades even, Rachel Edelman avoided writing poems about Memphis, the place she was raised. “I wrote a lot of very detailed nature poetry and poetry that engaged with climate change, catastrophe,” she says, “and while I think that certainly prepared me craft-wise for writing these poems, I, for a long time, didn’t want to write about the South or Memphis or my upbringing.”

As Edelman shopped around her first collection of poems, there was not a mention of her hometown in those verses. Instead, she explored a re-envisioned Exodus and the Jewish diaspora, with poems like “Palinode after Pharaoh’s Decree,” “What I Know of God,” and “The Tether” about Miriam, Moses’ sister. She revised and revised, but something was missing: Memphis, her own diasporic relationship with the city, and her relationship with her own family.

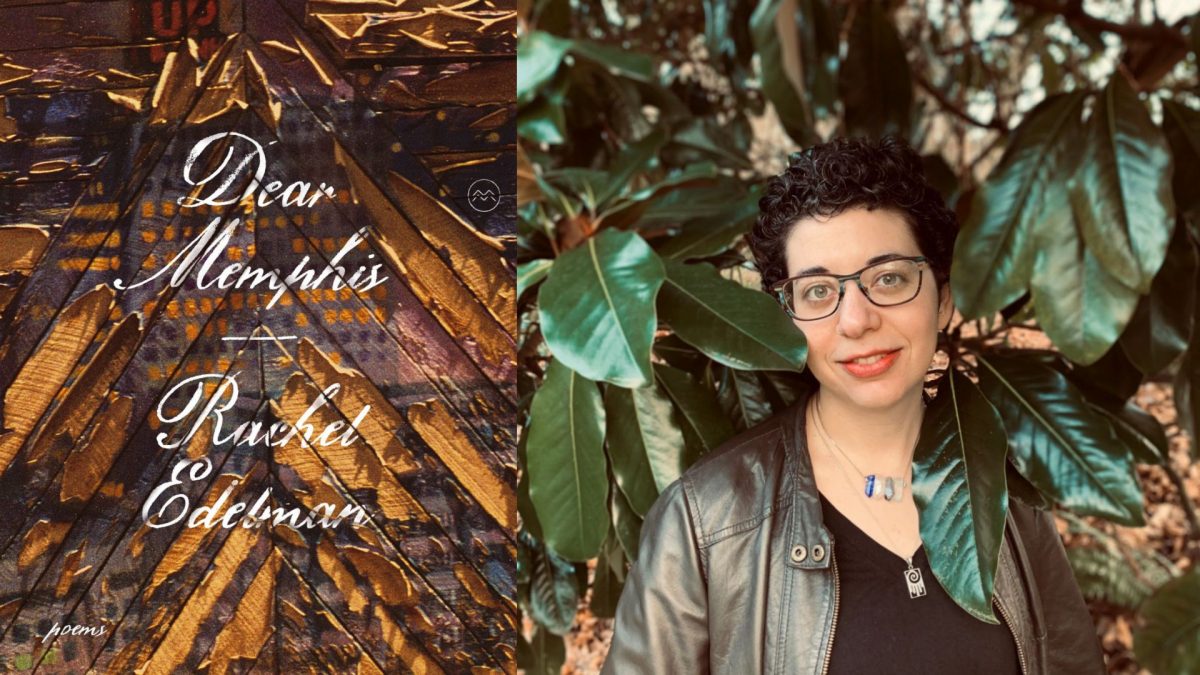

She titled the series of poems that came to be “Dear Memphis,” and their addition to her pre-existing collection made it complete, made it something new, something that connected her ancestors’ past to her present. This new collection would be titled Dear Memphis as well and was released in January of this year.

This weekend, Edelman, who’s now based in Seattle as a teacher, will return to Memphis to discuss and sign Dear Memphis at Novel (Friday, April 12, 6 p.m.) and Temple Israel at Crosstown (Saturday, April 13, 6:30 p.m.). In anticipation of her homecoming, the Flyer asked Edelman some questions about Dear Memphis and her poetry. See her answers below.

Memphis Flyer: You said that you avoided writing about Memphis previously. Why is that?

Rachel Edelman: In writing — at least in formal writing education settings — I was always taught to avoid sentimentality. And not to write — literally — not to write poems about your grandma. And [the writings in Dear Memphis] are poems very deeply engaged with that generation, with my grandparents’ generation, and the way that I have become a culture-bearer of theirs, and so I avoided it because I was told academically that it wasn’t high-class, quite honestly.

But then, in reading much more widely, there’s this poet — Aracelis Girmay — and reading her, “The Black Maria,” it showed me a way of incorporating archival research history, alongside personal story really, and it really moved me. It was both incredibly cerebral and incredibly embodied. And reading a work like that showed me you don’t have to choose. … And then speaking to other poets, who were writing gorgeous work that didn’t fear sentimentality, that didn’t fear emotion, I kind of opened up to writing these more personal poems. And while I don’t think that we necessarily need to lay all of our trauma on the page, I think it’s okay to welcome the more fallible and the more sticky moments as they come. … I think that there’s a lot of strength in veering into emotionally fraught territory.

What was the initial spark for your “Dear Memphis” poems?

I wrote those after doing the Tin House Summer Workshop, which was virtual in the summer of 2020. … [We were given a prompt to] write to somebody you’ve never met. You could write to someone who passed, you could write to a place or an idea, and I started writing “Dear Memphis” poems. And then I wrote them for a few months and they felt really intimate to me in a way that was important for the rest of the book. And they are probably the poems in the book that are revised least; they’re closest to their first draft.

Have you been back to Memphis since the collection has been released?

I haven’t. My family doesn’t live there anymore. My parents moved away in 2015, and grandma died in 2012. So the last time I was in Memphis was in 2017 for a residency at Crosstown.

But I am excited. And I also feel the distance that I’ve had from Memphis really acutely. Like, this is a book titled Dear Memphis, and for it to address Memphis, it requires a separation.

Does coming back to Memphis and living in Seattle feel like a diasporic experience on its own?

It does feel diasporic. [Memphis] feels like a diasporic home. My family lived in Memphis for five generations. I don’t know where else in the world my family has lived for that long because we are a diasporic people. And I firmly believe that Jews are a diasporic people, that we thrive in diaspora. And so, I don’t believe in a Jewish homeland, and I think it’s exciting to have many stops along our way along my lineage.

I think that these poems all engage with a vision of commitment to diaspora, … so that is really a thread that lines up for all of these poems. I also think that it’s an ethos that requires risk. It requires rejection of Zionism. And it requires a willingness to make overtures and alliances that may not work out, or that may require a lot of trust-building. So I think all of these poems are like gesturing at the complexities of that work.

Meet Edelman at Novel, Friday, April 12, 6 p.m., and Temple Israel at Crosstown, Saturday, April 13, 6:30 p.m.

Keep up with Rachel’s work at rachelsedelman.com, or follow her on Instagram @rachelsedelman.