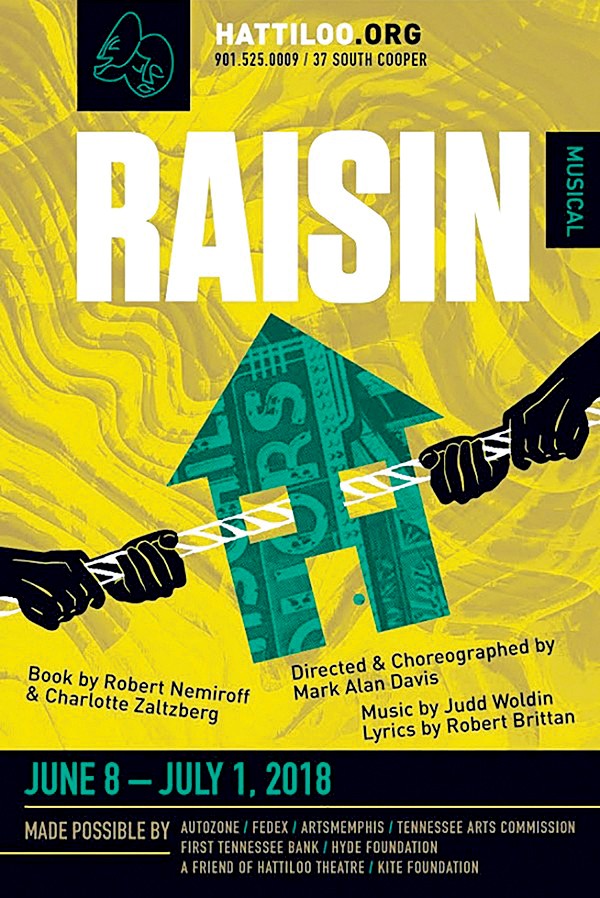

From a technical standpoint, I could pick Hattiloo’s Raisin to pieces. The set looks slapped together, the music’s canned, and that’s just for starters. But so much of any show’s success depends on material strength and a cast’s ability to leverage it. In this regard, everything about Raisin delivers. Music and dancing never water down the message in this faithfully adapted retelling of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun. This story of the Younger family and their struggle to buy an affordable home and possibly start a family business is a subtle, almost generous look at how America and its wealth became segregated. It is a deeply felt family drama that ends with a devastating loss barely tempered with dignity and determination.

As more and more Americans moved out of apartments and into single-family homes, the limited properties made available to African Americans were typically lower quality and far more expensive than property being offered to whites. Absent credit, it was sold via a contract system eliminating equity. One missed payment could result in eviction, with nothing to show for your effort. This is the legal, social, and economic environment in which Raisin unfolds.

Raisin isn’t about integration or white flight. It’s about a family’s struggle to create legacy inside a system designed to prevent it. The family patriarch has died leaving $10,000 in life insurance. Lena, the surviving matriarch wants to sink most of the money into an affordable home in a white neighborhood, not because of the demographics, but because “It was the best [she] could do for the money.” Her son Walter Lee’s a chauffeur who wants to invest the money in a family business — a liquor store. Her daughter has exchanged faith for science and wants to go to medical school. In the absence of credit or anything more than sustenance income, all these dreams hinge on one pot of cash. Add to this dynamic a white representative of the Clybourne Park neighborhood who wants to negotiate a kinder, gentler way to keep blacks out, and you have all the ingredients necessary for an emotionally honest and devastating primer in how everything went wrong.

Raisin‘s story is famously inspired by the poetry of Langston Hughes. More crucially, it’s informed by the Hansberry family’s personal experience in court, fighting the restrictive legal covenants and members-only neighborhood associations. Hers is a deeply sad but open-hearted critique of the American Dream, a Depression-era fiction embraced by President Herbert Hoover to sell the advantages of single family home zoning where ethnic groups were excluded, over crowded apartment-based urban living where anybody might move across the street.

Raisin‘s Lena became an almost instantaneous theatrical archetype. George C. Wolfe brilliantly lampooned that archetype in The Colored Museum‘s “Last Black Mama on the Couch” sketch. Hattiloo stalwart Patricia Smith never sits on a couch or plays to type. Her Lena shifts from thoughtful, nurturing, and wise, to superstitious, impulsive, and tyrannical. She struggles to create security for her family without realizing how restrictive security can be — or how tenuous. Smith exudes maternal virtue, but hers is a nuanced, warts-and-all take on a part the veteran performer could have easily phoned in.

Director Mark Allan Davis gets top-shelf performances from an ensemble cast that includes Rashideh Gardner, Samantha Lynn, Aaron Isaiah, and Gordon Ginsberg. But Kortland Whalum’s leave-it-all-on-stage take on Walter Lee Younger is really something to see. Whalum feels nothing lightly and his words and songs land like punches — some weak, flailing and ineffectual, some like haymakers. It’s as rich a performance as I’ve seen in ages, just at the edge of too much but never tipping over.

Walter Lee gets swindled, of course. I don’t think that’s a spoiler given the shopworn material. He’s one more casualty of unstable alternative economies created when people are isolated and shut out of the regular economy. The Youngers may be moving into a Chicago neighborhood, but in this moment Walter Lee becomes the embodiment of Hughes’ “Harlem,” and the “dream deferred.” Maybe this gifted, young, imperfect black man, who’s trying to do all the things he’s supposed to do but still can’t get ahead, will finally dry up like a raisin in the sun. Maybe he’ll fester like a sore or stink like rotten meat or sag like a heavy load. Maybe he’ll explode. In a beautifully manicured interpretation, Whalum gives you the sense it’s all on the table all the time.

Short take: This Raisin has some real problems. Telling one helluva strong story isn’t one.