Countywide Juvenile Justice Consortium

Countywide Juvenile Justice Consortium

In the year following the end of federal oversight, black kids are still treated more harshly in one key area of Shelby County Juvenile Court.

That’s the conclusion of some criminal justice reformers. But law enforcement officials say violent crime is real and rampant in Shelby County and punishment needs to be tough to meet it.

The key area reformers point to comes in transfers to adult court. Sometimes, when a minor commits a violent crime, they are moved from juvenile court to adult court, tried as adults. In regular criminal court, the sentences are tougher, the stakes of crime are much higher.

Shelby County Juvenile Court/Facebook

Shelby County Juvenile Court/Facebook

In Shelby County, the cases of 90 children were transferred from juvenile court to adult court in 2019. The figure is way above other jurisdictions in Tennessee. Transfers here were higher than in 2018, when federal monitors still watched the court.

At least 87 of the 90 children transferred to adult court last year were children of color, and 86 of those were black, according to Josh Spickler, executive director of Just City.

“It’s appalling,” Spickler said. “The county is 53 percent African American, and this is our county juvenile court. So, there’s a clear disparity. There always has been. So this is no surprise.”

[pullquote-1] This disparity is what brought federal monitors from the Department of Justice (DOJ) in 2012. They watched the Memphis and Shelby County Juvenile Court until October 2018, leaving after many local leaders urged them to conclude their work.

In February, Juvenile Court Judge Dan Michael declared “mission accomplished” during his state of the court address, touting the end of federal oversight.

However, many — including Shelby County Commissioners Van Turner and Tami Sawyer — said more work was to be done.

“So this whole notion that it was a successful closure, I think is somewhat fabricated,” Turner said.

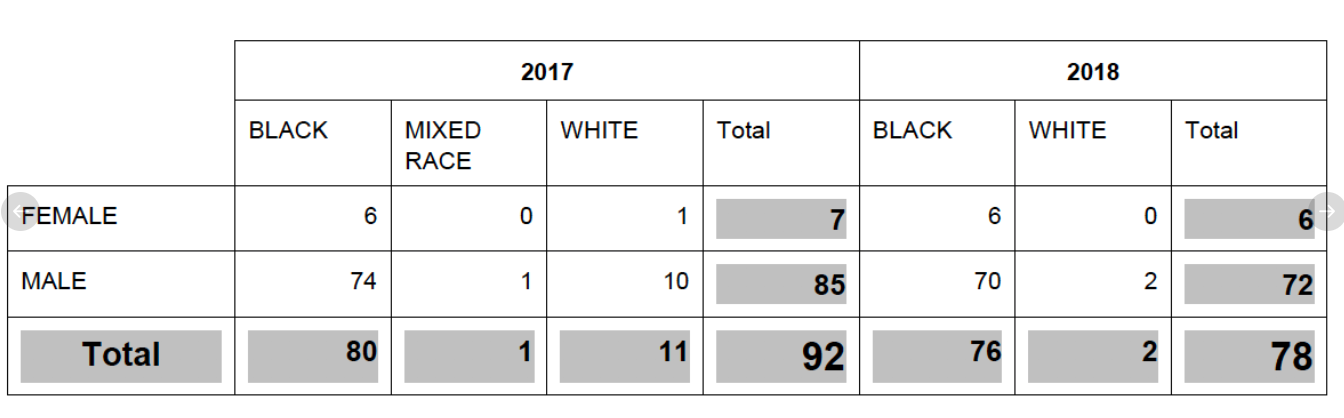

In 2017, 92 cases of children were transferred from juvenile court to adult court. (That same year, four such cases were transferred in Nashville.) In 2018, the transfer number fell to 78 (76 of them were black, according to Just City). Last year (the first full year since federal oversight ended here), the number rose to 90.

Just City

Just City

Transfers to adult court must be first requested by prosecutors in Shelby County District Attorney Amy Weirich’s office. After that, the decision is up to a judge or magistrate.

To warrant a transfer to adult criminal court, the offense has to be serious, and Weirich says they are, and crime here is unlike it is in the rest of the state.

“We are not Davidson County or Hamilton County,” Weirich said. “We are Shelby County. And in Shelby County in each of the last three years, over 600 serious violent crimes — murder, rape, robbery, kidnapping — have been committed by Shelby County juveniles on Shelby County victims.

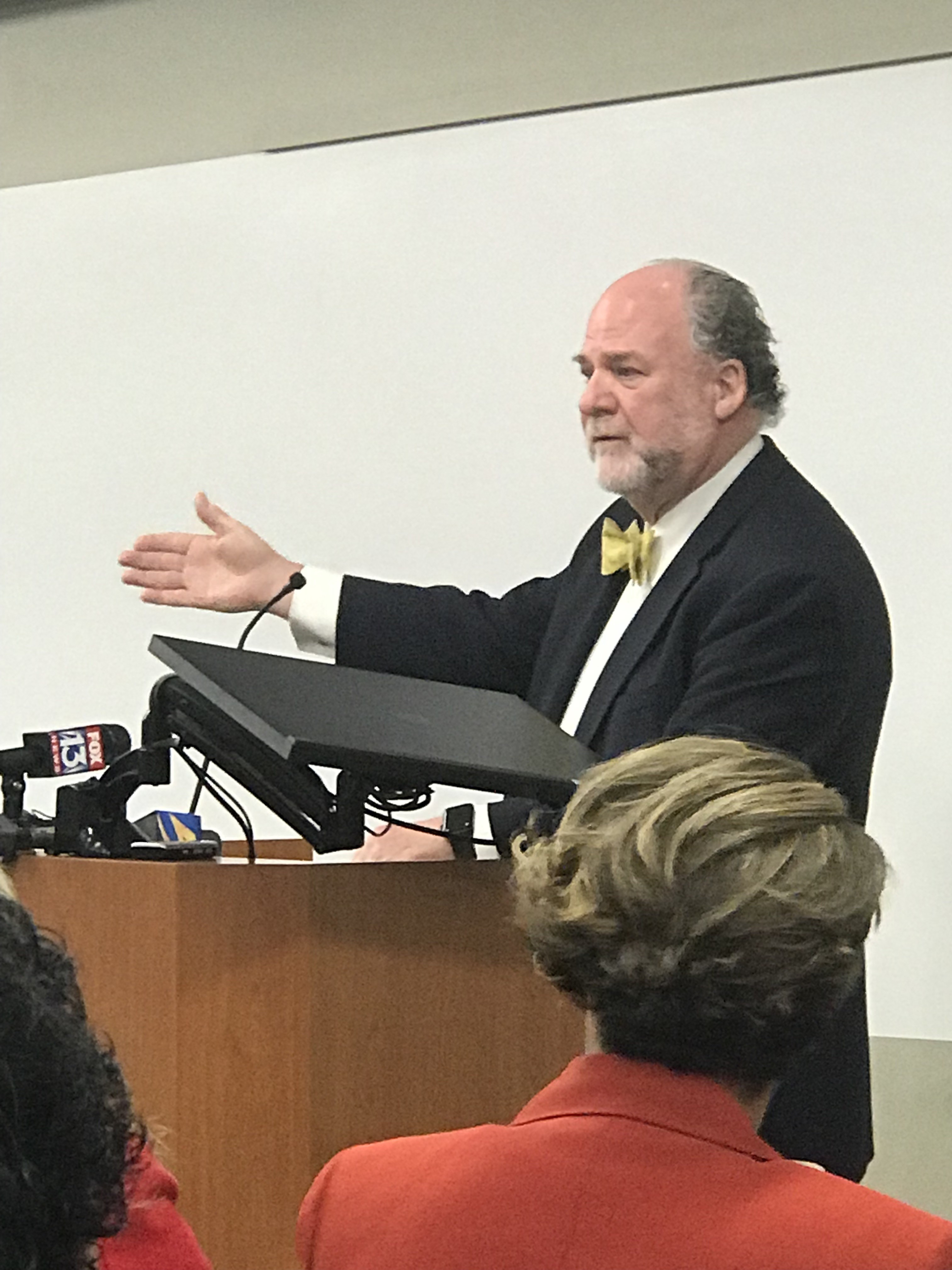

Toby Sells

Toby Sells

Memphis and Shelby County Juvenile Court Judge Dan Michael declared “mission accomplished” during his annual state of the court address last year.

“Of those 1,800-plus cases, transfer was the only option we had in 255 of them because of the offender’s record and the violent facts of the case.”

Weirich said that nearly half of the transfers — 125 of 255 — were voluntary, by the defendant through an attorney. The rest were ordered by a judge or magistrate after hearing the evidence of the case and reviewing the child’s record.

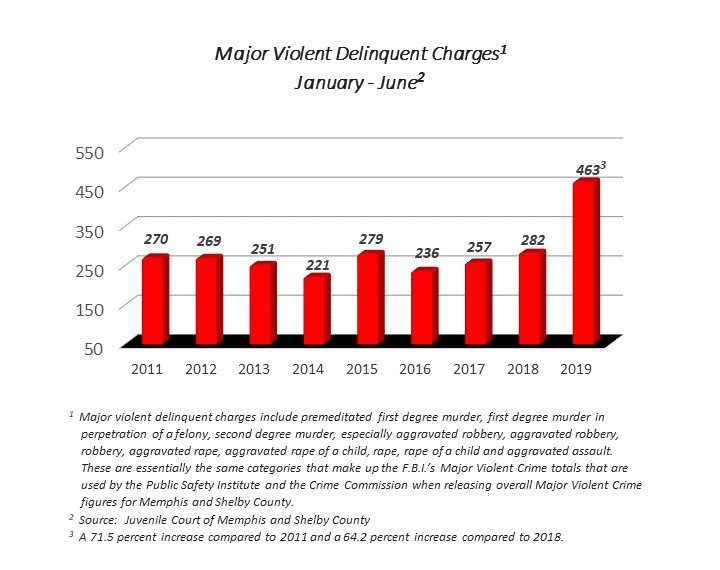

In August, the juvenile court here reported that overall charges against youth in Shelby County were down 9 percent in the first six months of 2019 (a total of 3,096 charges). It was good news, according to law enforcement officials.

However, the rate of violent crimes (murder, rape, robbery, and other offenses) committed by juveniles in that time period surged. In the first six months of 2019, 463 charges of violent crimes by juveniles were filed. That was up from 282 such charges in the same time in 2018.

But once juvenile offenders got to court, federal monitors found a host of problems. The court allowed “blatantly unfair hearing practices” that limited the ability of defense attorneys to represent their clients, according to a DOJ report. Other practices impeded due process, like denying psychological evaluations prior to a juvenile’s transfer to adult court. The report also said the court fostered a culture of intimidation against defense attorneys.

Memphis Shelby Crime Commission

Memphis Shelby Crime Commission

Couple those facts with the outcomes of another DOJ report on discriminatory outcomes in juvenile court, “and you have a recipe for injustice,” according to Bill Powell, who served as the county’s juvenile court monitor until 2017.

“If you look at the reports, I don’t think [the numbers of transfers to adult court] are surprising,” Powell said.

He said comparing the transfer rates of Shelby County and Davidson County were important. (Again, in 2017, Shelby County had 92, and Davidson county had four.)

Just City

Just City

“We have the same laws; the difference lies in the administration of those laws,” Spickler said.

Spickler said different cultures govern the Shelby and Davidson County Juvenile courts and ours says something about who we are.

“This is an issue that impacts the whole county, and these are our children,” Spickler said. “This says a thing about every single citizen in Shelby County. This is what we’ve accepted.

“This is how we want to deal with children who need correction, who need support and rehabilitation, and we’re going to deal with them much differently when they’re black.”

As of press time, no one from juvenile court had responded to a request for comment.