In little more than a month following the publication in May of his fourth book, Red Hot and Blue (Chicago Review Press), Memphis writer Stanley Booth experienced a moment in which those close to him feared he might be called upon, in the words of a well-known Dylan lyric, to go knocking on Heaven’s door. Hospitalized for a scary spell and, as we speak, undergoing rehab, the 77-year-old Booth would seem to be on the mend, and his conversation these days turns ever more to the idea of completing yet another volume.

This would be The Pea Patch Murders, a long-planned treatment of some true-life skullduggery that occurred a century or so ago on the soil of the author’s native Georgia.

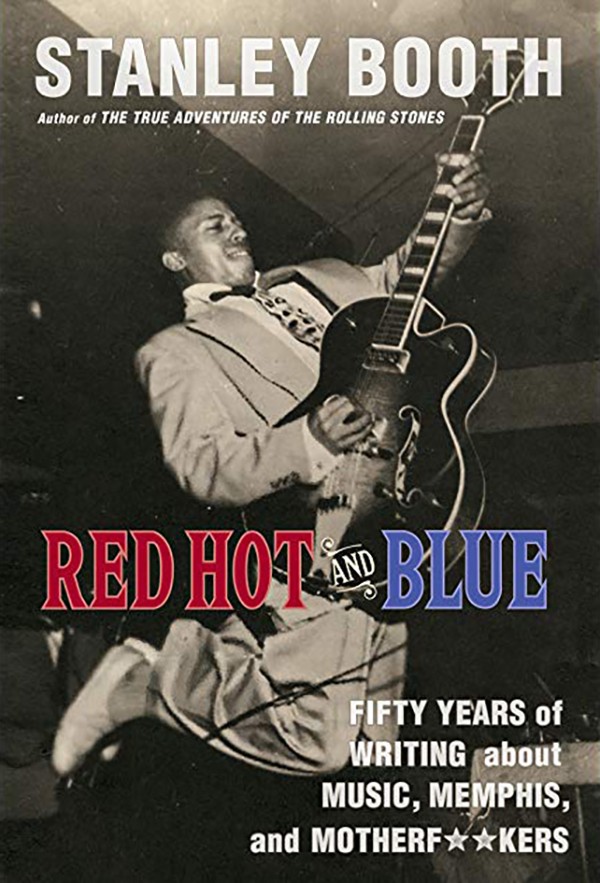

Meanwhile, the present volume has assembled 29 pieces, subtitled accurately as “Fifty Years of Writing About Music, Memphis, and Motherf**kers,” that go far toward illuminating matters of another kind — including, here and there, the pivotal one of existence. Booth, considered by many to be a nonpareil rock writer, prefers to be known as a “writer,” pure and simple, with no adjectives.

It is a fact, though, that Booth has mostly focused his attentions on matters musical and in particular on the major themes and movements of popular music, both in the American heartland (especially within the cornucopia of Memphis-related sources) and worldwide, as in his masterpiece, The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, first published in 1984, a story of the Stones from their beginnings as working-class English R&B enthusiasts through the crucial year 1969 that culminated in the fateful free concert at Altamont, California.

Like those English troubadors and numerous others on both sides of the Atlantic, Booth has clearly operated under the spell of roots music and the practitioners of the blues, past and present. Red Hot and Blue is a testament of sorts to that fact, blending encyclopedic detail, revealing anecdote, on-point analysis, and, in many cases, Booth’s personal experiences. The book repeats several of the aricles from the author’s 1991 anthology, (the purposely misspelled) Rythm Oil, often in a newly expanded, unexpurgated form. Other pieces — notably the transcript of a proposed TV documentary on Memphis music and a scenic treament of a film biography of iconic Memphis rhythm-and-blues DJ Dewey Phillips — are brand new.

A number of the subjects dealt with in Red Hot and Blue, like Blind Willie McTell, Joe “King” Oliver, and Ma Rainey, preceded the author’s time, but Booth has done his research and provides good and sometimes graphic accounts of their lives, ordeals, and oeuvres. Other chapters are essentially biographical interviews, in which the artists, prodded at appopriate intervals by Booth, get to tell their own stories; cases in point are the white jazz-blues icon Mose Allison and bluesmen Bobby Rush and Marvin Sease.

A fair number of the chapters are long takes on figures Booth has known and interacted with. In many of these, the author’s own experiences are an essential part of the tale — most memorably, perhaps, in the two sections on ur-Memphis blues singer Furry Lewis. The first of these, “Furry’s Blues,” was the oldest Booth article to be written, circa 1966, but not published until 1970, when Playboy Magazine awarded it a prize for nonfiction. In it, Booth documents the hard but noble life of Lewis, an early blues recording artist reduced to the drudgery of a street-sweeping job. The article was an important factor in a late rebirth of Lewis’ career and reputation.

The author’s first chapter, “Blues Dues,” differentiates between experiencing blues — and life — at the street level and coming to either through the medium of a record collection. The book ends with the aforementioned Dewey Phillips treatment, a loving take on the life and tragic death of the man who, on a late-night program called, yep, “Red Hot & Blue,” first played an Elvis Presley record on the radio, thereby launching a revolution.

In between are chapters on Elvis, James Brown, Phineas and Calvin Newborn, Otis Redding, photographer William Eggleston, Dr. George Nichopoulos, Charlie Freeman, and others too numerous to mention and too compelling not to read about.