This art will be the end of us!

The year was 2002 and five little words had some of Memphis’ most prominent white Conservatives frothing at the mouth: “Workers of the World Unite.”

From a cover story I wrote at the time:

In 1934, the First All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers adopted the principle that art should promote only a rigid slate of political and social ideals established by the state. This movement was dubbed Soviet realism.

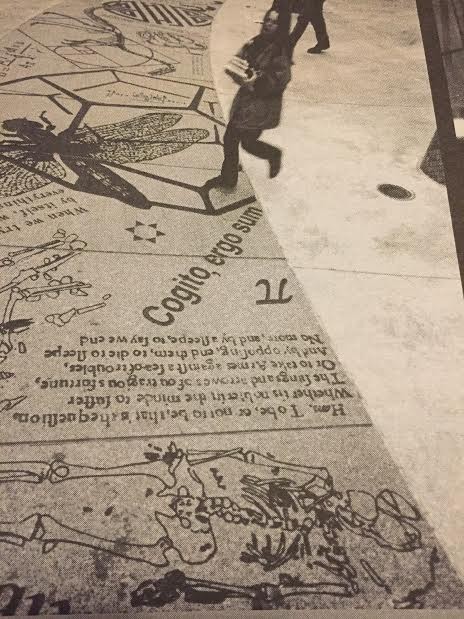

In November 2001, Memphis City Councilman Brent Taylor, and Shelby County Commissioners Marilyn Loeffel and Tommy Hart, took umbrage at one of nine public artworks sponsored by the UrbanArt Commission (UAC) for the new $70 million Central Library. Their aim was to have an offensive quotation removed from a public walkway because it expressed a sentiment which they deemed to be out of step with wholesome American values.The irony grows sweeter considering that the offending “Workers of the world, unite!” is excerpted from The Communist Manifesto, which sparked the revolution that eventually birthed the school of Soviet realism whose precepts were unknowingly co-opted by Taylor, Loeffel, and Hart.

A pious group of Memphians led by one William W. Wood of the hastily organized Shelby County Coalition to Save the Memphis Library began a biweekly vigil to pray over the wicked artwork. The same group sent out scorching mass e-mails comparing the presumably elusive UAC with Osama bin Laden and labeling the board and administration of the Memphis/Shelby County Library “a special branch of the CIA.”

Toss in the eccentric patriot in a red, white, and blue suit who makes regular protest pilgrimages to the site and you have all the ingredients for an old-fashioned dog-and-pony show. Even The New York Times got in on the action, noting that “The cold war may be over, but Marx and Engels have nevertheless managed to create a small political furor in this old river city.”

The backlash came as a complete shock to Brad and Diana Goldberg, the Dallas-based husband-and-wife team responsible for designing the artwork. They intended that their piece function as “a metaphoric record of important events and knowledge that have shaped Memphis, the Mississippi River Valley Region, and the rest of our world” since the beginning of recorded history.

It was less of a shock to local political columnists who practically stumbled over one another to spank Taylor, Loeffel, and Hart for striking such a provincial pose. Susan Adler Thorp aptly observed in The Commercial Appeal that “Tearing down the Iron Curtain and destroying communism were simple tasks compared to accommodating [their] need for political opportunism, and logic.”

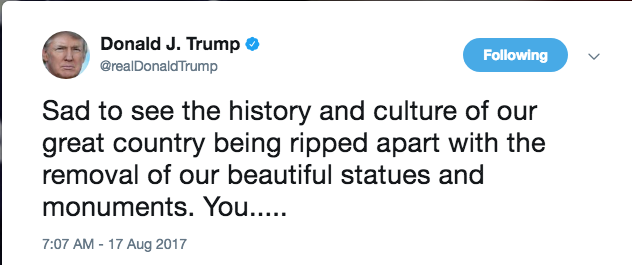

Why mention this vintage kerfuffle? Because debate over the removal of Confederate monuments rages on in comment sections across the World Wide Web. It’s nasty, getting nastier, and even the President of the Comment Section himself, Donald J. Trump, weighed in on the side of White Supremacy. I’m revisiting it because there was a time, not so very long ago, when white Conservative Christians — spearheaded by elected officials — thought it was wrong to memorialize the enemies of America.

Thing is, the library sculpture aimed to reflect world-changing ideas generally, and wasn’t political in nature. It certainly wasn’t ideologically aligned with Communism, and guess what? Memphis didn’t transform into a hotbed of socialism. The hullabaloo blew over. People mostly forgot it was a big deal and the piece just kind of blended into the landscape, as it was intended to — like concrete and granite shrubbery nobody ever had to water.

But let’s not kid ourselves. It wasn’t JUST the Communist history upsetting the easily upsettable. In a right-to-work environment, it was also the out of context message of worker unity, divorced as it was, of its Marxist origin. Nothing’s more terrifying to the unreconstructed set like the idea of a united working and underclass or any unified threat to the hegemony. This has always been true.

Public response to public art is directly and proportionally-related to public values and the degree to which those values are reflected in the work. That’s why modernism in the public sphere met with so much backlash at the end of the last century. As one heartland critic noted in the 1970’s: “I think people are tired of New York Arty-art. You can keep it in museums where it won’t bother anybody.” Coming full circle, abstract work becomes attractive in the public sphere again for the exact same reason — people can’t ascribe values, making it harmless. We tend to divorce the Confederate memorials from similar conversations about public art. Probably because it clears the fog of war and makes the question of values (or negative values) so apparent.

All art speaks to the future, and public art speaks with authority. That’s why this battle has been so bitter. It’s not about the past, it’s for the future. As the City of Memphis, spurred on by united activists, creeps forward with plans to execute this long-overdue removal (a process gummed by Tennessee’s regressive and cowardly state legislature) I thought it might be interesting to remember when all those people down in the comments today screeching, “history,” and “heritage,” were out in the street chanting (okay, praying) “tear it down!”