Memphis music lost one of its giants this week with the passing of Isaac Hayes, who died at his home Sunday at age 65.

A Manassas High School graduate who went on to become a central figure at Stax both as a songwriter and session player in the 1960s and then as a monumentally successful solo artist in the ’70s, Hayes’ larger-than-life public image and variety of cultural achievements might be eclipsed in the annals of Memphis music only by Elvis Presley.

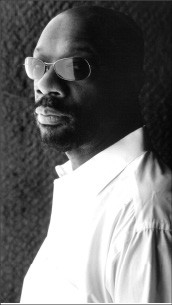

When Hayes made the transition from behind-the-scenes genius to superstar, he became as much a style icon as a musical one. He embodied that decade’s changes in black culture — the transition from blues and soul to funk and disco — like perhaps no other musician. The ambition and flamboyance of his music and persona — the eye-popping wardrobe, shaved head, and omnipresent sunglasses — made him one of the era’s signature figures.

My personal interactions with Hayes were minor. As a critic, I grieve for how little his pre-’70s work is understood and acknowledged. While Hayes’ solo material in the ’70s had considerable peaks — his slow deconstruction of “Walk on By,” the clattering funk chaos of the galvanic “Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic” (sampled brilliantly on Public Enemy’s “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos”), and, of course, his swaggering “Theme From Shaft” — I suspect that his perfect partnership with fellow Stax staffer David Porter may have been his greatest purely musical gift to the planet.

Together, Hayes and Porter wrote some 200 songs, among them the Sam & Dave classics “Soul Man” and “Hold On, I’m Comin’.” In Hayes’ Associated Press obituary, this prolific work received about half as much ink as Hayes’ late-life performances on the animated television series South Park.

There was considerable art behind Hayes’ compelling image, much of it created before many music fans even knew his name. As time goes on, his legend is unlikely to waver. Hopefully, the depth of his work will be remembered as well.

— Chris Herrington

The best thing in the world

Getting to see Isaac Hayes’ career skyrocket always has been a cherished childhood memory for many kids like me, who grew up in South Memphis. He was our attainable icon, a living, breathing example of life’s possibilities.

I was a bit luckier than most. My mother worked in a beauty shop called Ethel’s, which was on the same block as Stax. There was Jack’s grocery store, the beauty shop, Stax Recording, and the Satellite record shop all lined up, making one safe, beautiful world for the kids in the neighborhood.

Back then, Isaac was just one of the many guys filtering through, trying to meet one of the ladies getting pretty or bumming change to get a hot dog at the Satellite Cafe.

One day, Isaac’s writing partner, David Porter, came in and grabbed a couple of customers, my sister Carolyn among them, to come and sing on a record they were making. The song was the Bar Kays hit “Soulfinger.”

Not long after, Stax bought out the whole block. Miss Ethel moved her shop to Glenview, so Mom and her best friend bought their own shop across the street at McLemore and College.

A lot of the Stax guys still came in and got their hair done, bringing over new records and sometimes even tickets to shows. And then the coolest thing in the world happened: Isaac released the album Hot Buttered Soul and became a superstar. Then he wrote the soundtrack for the movie Shaft and won an Academy Award!

Right after that, he bought his gold Cadillac Eldorado. But even after becoming the biggest thing in Memphis since Elvis, Hayes bought a house in

Longview Heights at Frank and Lauderdale streets. Even cooler for us kids, he kept about half a dozen of the latest cars parked on the street in front, and we’d see them every morning on the way to school.

After school, it was a regular deal to see him in his yard playing with his kids or throwing the football around with some of the older fellas — while dressed in rainbow pants, leather outfits, and monkey-fur boots. It was the best thing in the world. And seeing him on such a regular basis in our neighborhood let us know that whatever we dreamed of, we could achieve.

Godspeed, Mr. Hayes. We’ll miss you. And thanks. — Tony Jones

Tony Jones is a local writer and occasional contributor to the Flyer.

Talkin’ ’bout — and listening to — Isaac

Hustle & Flow had long since wrapped its principle photography and was well into the editing process. We were about to lock the picture when Isaac Hayes came into the studio to record additional dialogue. It was the longest stretch of time I was able to really talk with him about growing up in Memphis. He was delighted to discover that I had been studying the 1968 sanitation strike for a future project.

“I was at Mason Temple the first time King spoke to the sanitation workers,” he explained. “I was also in that march with King, the one that turned violent.”

Suddenly everyone in the studio went silent. Every technician stopped what they were doing so they could listen to Isaac tell the story.

“Windows were breaking all around us. Cops started clubbing us. We were all trying to get back into this church, but the doors were locked. A nun was next to me with tears streaming down her face because of the tear gas. Then they sicced the dogs on us. And I was kicking them off of me and the rest of us.”

Isaac is known by many titles. I was privileged to call him a friend. The world knew him as an artist, an actor, and an activist. But whenever I picture him kicking a German shepherd off a blinded nun in the middle of a riot, the only description that pops into my mind is that of one bad mother. . . shut your mouth!

I’m just talkin’ ’bout Isaac.

— Craig Brewer

Filmmaker Craig Brewer directed Isaac Hayes in Hustle & Flow.

“That brother is bad.”

When I was a child, Isaac Hayes was a favorite of my parents. My daddy used to always say, “That brother is bad.” I knew Isaac as a solo artist, and it wasn’t until I was in my 20s that I came to understand his role as a songwriter and producer.

I was raised on Isaac Hayes. His classic songs were the soundtrack to my childhood and left an imprint on my musical taste. I still have the copy of Hot Buttered Soul that I stole from my mother’s record collection. It’s the record that showed the world that Isaac Hayes was more than a hit songwriter. It revealed him as a superstar.

The first time I met the man, the myth, the legend, I was a bit speechless, a rarity for me. He was gracious, warm-hearted, and responded to my nervous greeting with a smile that said, “Don’t worry about it, little sister.” We crossed paths many times afterward and he always offered a deep, resonant hello that could put anyone at ease.

A few years ago, I had the pleasure of doing publicity for the Memphis opening of Isaac’s Peabody Place restaurant and club. The job was my opportunity to make up for being born a couple of decades too late. Isaac was pleased to see his name in lights, but he was more excited about being surrounded by his friends and family. Over the years, we all saw Isaac’s career in its ups and downs, and he took it all in stride. As other artists were busy reinventing themselves, Isaac Hayes stayed the same, just revealing different sides of himself. After his stroke in 2006, many thought Isaac would never be the same. However, we saw him fighting his way back to health, and he never once lost his cool.

Just weeks ago, I was interviewing producer Terry Manning at a Memphis

Music Foundation workshop and asked him about recording Isaac’s version of “Walk On By.” Manning reminisced about the magic of that day and the genius of Hayes. Tonight I find myself listening again to Hot Buttered Soul, remembering the music that altered my life. For me and many of my friends, the passing of Isaac Hayes is the most significant loss to Memphis music since the death of Elvis.

— Pat Mitchell Worley

Pat Mitchell Worley is director of development and communications at the Memphis Music Foundation, host of Beale Street Caravan, and an occasional Flyer contributor.

The Deliverer

Though I once co-taught a course at the University of Memphis on the history of rock-and-roll, Isaac Hayes was something of a lacuna for me. I never knew as much about him as I wanted to, nor listened to him as much as I thought (as I knew) I should have. And though I saw him several times around town in recent years, the most visibly affected I ever was by him had been an occasion when he wasn’t even there.

It was in Colorado in 1981, at an off-the-beaten-path tourist attraction, where I saw on display a really elaborate motorcycle billed as Isaac’s — a huge, gilded, chrome-laden thing. It had been acquired by somebody after a bankruptcy of his, I think, and now was a geegaw for strangers to gawk at.

That was during a rough spell of my own, and the image of that bike never left me as a symbol of loss. In time, as I learned more about Isaac, it also served as a contrast to the genuine, understated modesty of the man with that monumental mellow voice. I had heard a few songs from Hot Buttered Soul when it first came out in 1969 and was amazed that a man with such timbre at his command would have been content to subordinate himself to other singers for as long as he did.

Part of the answer to that, of course, was that his composing jones was every bit as strong as his need to perform. In fact, it is one of the illustrative ironies of the Stax-Volt era in particular and the nature of music in general that such an anthem of assertion as “Soul Man” should have been co-written by him and David Porter, his frequent partner in songwriting and a man as essentially genial and self-effacing as Hayes himself was.

When you look and sound the way Isaac Hayes did, though, it’s not likely that people will let you hide your light under a bushel. It was inevitable that he would find himself cast — as the title of another classic early album would have it — as a Black Moses.

The most illuminating thing I ever read about Isaac came in a 2001 Q&A conducted with him by my Flyer colleague Chris Herrington. Hayes was asked why so many of the songs written by him and Porter for others sounded so different from the ones he himself sang. Isaac’s answer revealed the man: “The songs that we wrote for other people were things that I couldn’t deliver on as a singer.”

That’s something only a man with genuine soul could say. Isaac Hayes delivered plenty. — Jackson Baker