If you’ve seen the film Into the Wild, Sean Penn’s 2007 biopic about doomed, Alaska-bound drifter Christopher McCandless (or read the eponymous book by Jon Krakauer), then you probably know about the artist Leonard Knight. On McCandless’ way to the great North, he briefly stops at Knight’s “Salvation Mountain”— a big, painted rock in the middle of the SoCal desert.

Knight passed away yesterday at age 82.

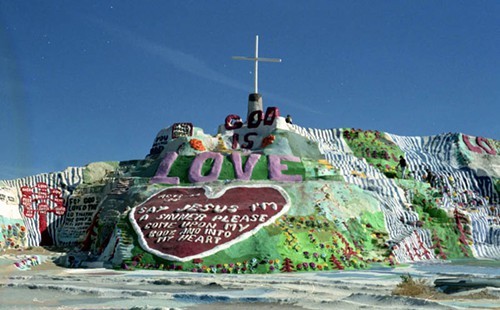

Knight’s mountain, visible on Google Earth, reads “GOD IS LOVE, JESUS I’M A SINNER PLEASE COME UPON MY BODY AND INTO MY HEART.” It is painted (in bright latex) to resemble an Eden, a waterfall, a valley of the shadow of doubt, a Gethsemene. It backs up against Slab City, a neighboring desert community of off-season Burning Man attendees and trailer-dwellers. Knight spent over 30 years crafting his mountain in ascetic conditions, and the result doesn’t look, or feel, quite like anything else in the world.

I got a chance to meet Knight a few years ago. He would have been about 79 when I passed through the area, and at the time he was still spry. He gave my friend and I (plus a prayerful full-leather biker and a group of wayward crust punks) a tour of the Mountain, pointing out sections that had been fabricated from old tires and rail ties, or else carved laboriously out of the rough ground. We brought him a bucket of hot pink paint because we’d heard it was customary to bring paint in exchange for his tour. He told us that his goal was to spread the love of God and that he was glad that his work was getting attention.

Knight has been written about as a visionary artist (an expansion on the term “self-taught artist”, as many informally schooled artists have been called). His work falls in with that of painters Howard Finster and Bill Traylor, as well as with Memphis’ own “Saint Paul’s Spiritual Temple”—or Voodoo Village. Much outsider work (as it is also sometimes called) is spiritually-themed and highly colorful. But Knight’s mountain is bigger and weirder and less salable than most outsider art, and so—even as it is the most visible piece in its genre—there are still concerns about its preservation.

Hopefully (and probably) Knight’s work will meet a better fate than “Saint Paul’s”, which fell victim to vandalism and abandon after the 1960s. For now, if you’re ever driving around in the desert south of Los Angeles, you can stop by and remember what Knight said about his work and faith in Into the Wild: “This is a love story that is staggering to everybody in the whole world.”