Freight trains are blocking railroad crossings for longer periods of time in Tennessee, according to a government report, which poses possible public safety risks. The issue has caught the attention of the state and local leaders.

Memphis City Council members vented frustration on the issue last month, grilling a freight company official on what would be a “reasonable time” for trains to block roadways here. Now, a new state report calls these blockages “dangerous” and a “safety issue gaining attention nationwide.

For Memphians, delays for streets blocked by rail crossings can be a daily experience. A new report from the Tennessee Comptrollers Office defines them as: “instances where a train is stopped, blocking a highway-rail crossing so that motorists and pedestrians cannot use it.”

The delays can be annoying, stopping the flow of traffic for uncertain lengths of time. But Tennessee State Comptroller Jason Mumpower takes the delays a step further.

“Blocked crossings are dangerous because individuals may be tempted to crawl between stopped railcars and be injured if the train begins to move unexpectedly,” reads the report. “Also, communities and citizens may be critically affected when police and emergency services are prevented from or delayed in reaching their destinations.”

The Federal Railroad Adminstration (FRA) collects reports of blocked crossings. The agency has an online portal for incidents. The state of Tennessee has a portal to that portal on its website, as well.

Blockages can also be called in. Crossings typically have blue signs that read “report problem to …” listing a phone number and the identifying number of the railroad crossing.

Blocked crossings are increasing across the country, according to a 2019 report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO). One reason the report cited: Freight companies are making their trains longer to increase efficiency and decrease costs, with some trains reportedly more than three miles long. This can lead to delays as engineers inspect each car, looking for mechanical issues.

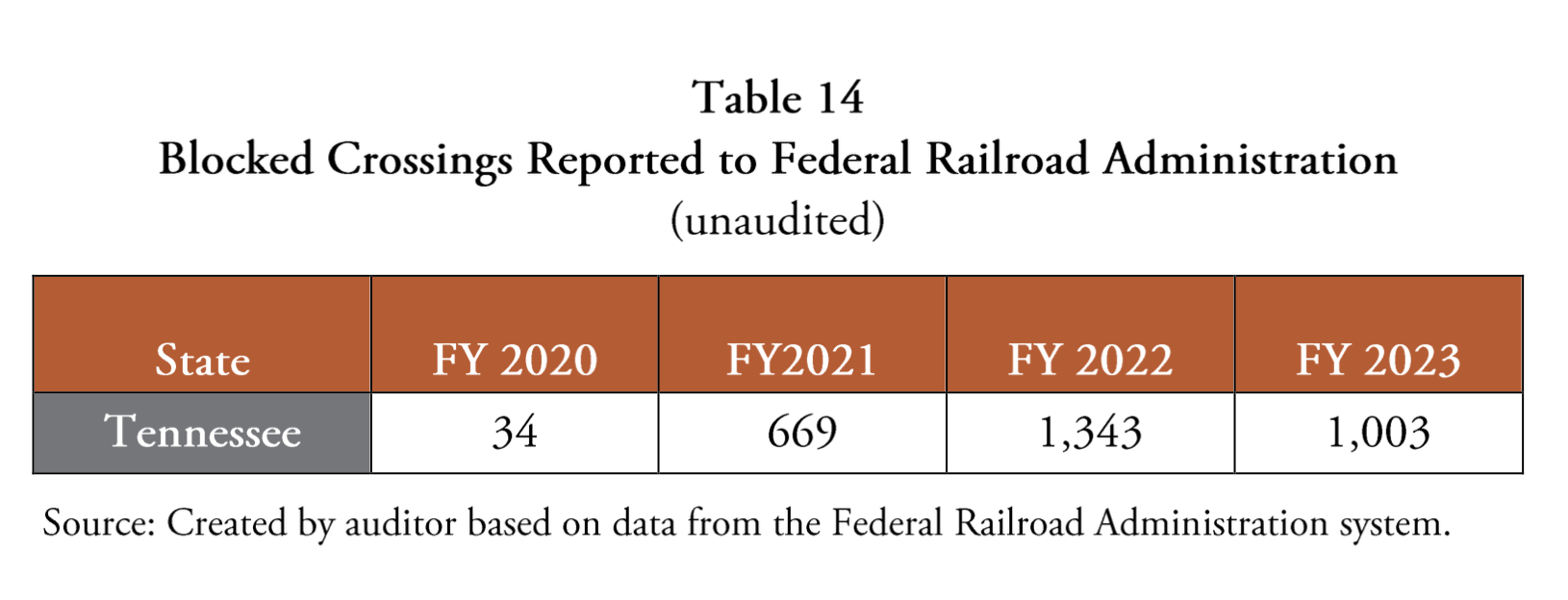

Last year, the Tennessee General Assembly asked the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT) for an annual report of the number of blocked crossings. The numbers have fluctuated over the years for reasons not outlined in the report but have risen from double- digits in 2020 to more than 1,000 over the last two years.

Memphis does not rank anywhere near the top of that annual report. Observers here reported incidents at 13 crossings in 2021-2022, compared to nearly 46 in top-ranking Nashville that year.

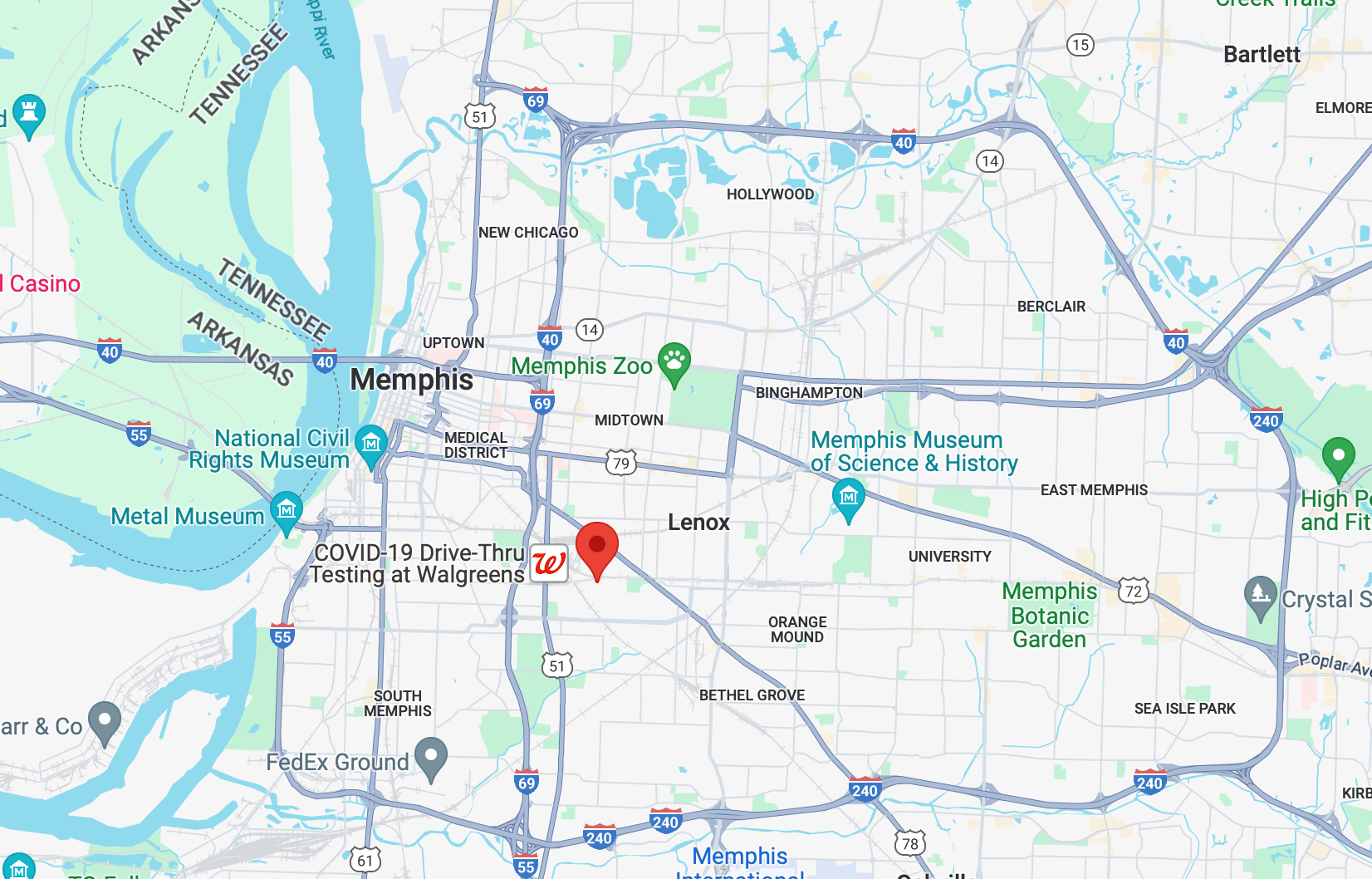

The most-reported blocked railroad crossing in Memphis that year was 732192R. It’s on a line owned by Norfolk Southern and crosses McLeMore Avenue, close to Southern. It was reported blocked by citizens 11 times in 2021-22.

The following year, it was reported as blocked only five times. However, that FRA report has more detail on the blockages. In March 2022, the crossing was reported to blocked for 6-12 hours by a stationary train and ”pedestrians were observed climbing on, over, or through the train cars.” In April, a train blocked the crossing for more than a day, according to a report. In May, “first responders were observed being unable to cross the tracks.”

No Tennessee or federal law penalizes railroad companies for blocked crossings, according to the Comptroller’s report. Some states have tried to bill the companies for the blockages, but rail companies then take the issue to the federal level. They’ve never paid a blocked crossing fee in any state, according to the Comptroller’s report.

In 2021, federal lawmakers introduced the Don’t Block Our Communities Act, which would have created a 10-minute time limit for train crossings. The bill was failed to pass.

Memphis already has a time limit: A city ordinance says trains can’t block a crossing for more than five minutes. The law does not apply to trains in motion. No fines or fees come with breaking the law.

Last month, Memphis City Council members brought in Michael Garriga, director of government affairs for BNSF Railway, to start a conversation on the topic. He described the company’s operation here as a big business, with customers such as Nike, Amazon, Walmart, and Kellogg. He also described the rail system in and through Memphis as a complicated one with numerous networks and cooperative agreements with other rail companies.

Council member Cheyenne Johnson asked Garriga, “What should the average time-frame be for a person waiting for a train to pass?” That answer was complicated, too, he said.

“I hate to answer it this way but it’s the only way I know how to answer it,” Garriga said. ”It’s going to vary because every train is different.”

When pressed further to say what would be a “reasonable amount of time” for a train to pass, Garriga didn’t answer because he said he didn’t know. But he reminded council members that he lives in the area and deals with blocked crossings, too.

“I understand the frustration but there’s a service there; there’s a part of the economy that’s moving,” he said.

Council member Jana Swearengen-Washington invited Garriga to speak because her constituents were “very concerned about” slow or stationary trains. She asked Garirga if anything could be done about the issue.

He said the companies could possibly communicate better about train switching schedules. He also suggested the council explore a new federal program to eliminate some railroad crossings with infrastructure projects, which could take years to complete.

Swearengen-Washington said she will continue the conversation at Memphis City Hall, with a promise to bring in another railroad official to speak before the council soon.