- JB

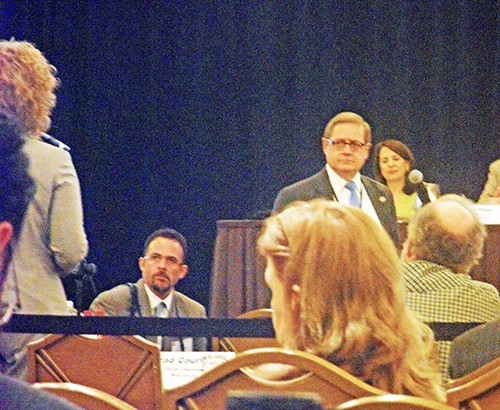

- Ryder faces off against critic Orrock

Thursday was a big day for Republicans in Shelby County. It was the second round of the Republican National Convention’s annual spring meeting, a three-day affair taking place at The Peabody through the auspices of Memphis lawyer John Ryder, the RNC’s general counsel.

Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam had earlier addressed an RNC luncheon meeting , and, as a culmination of the day’s activities RNC members from across the nation were girding to hear an evening speech by Florida Senator Marco Rubio, one of two bona fide 2016 presidential hopefuls on hand — the other being Kentucky Senator Rand Paul, scheduled to speak to committee members on Friday.

As a sort of stand-alone adjunct evening, meanwhile, local Republicans were gathering Thursday night at the nearby Central Barbecue location downtown for a “unity rally” in the wake of this week’s just concluded countywide primary election.

But the most significant GOP event of the day, to the world at large as well as locally, may have been a meeting of the RNC’s Rules Committee Thursday afternoon — one which took a major step toward transforming the way in which Rubio, Paul, and the other potential presidential candidates of the 2016 election season are presented to a national public.

The aforesaid Ryder began the Rules Committee meeting by introducing an amendment to “10H,” the RNC rule governing participation by candidates in presidential debates. Contending that only 7 percent of media members were Republicans, Ryder drew a portrait of a party whose prospective leaders in 2011 and 2012 had been hamstrung and misrepresented in televised national debates.

There had been 23 debates between Republican candidates, all totaled, too many and all of them too much under the sway of a media that was 93 percent hostile, said Ryder, who contended the result had been harmful — perhaps fatal — to the GOP’s hopes of gaining the White HOuse.

Hence, his amendment — the product, he said, of extensive deliberation among members of a previously unpublicized ad hoc RNC group, apparently appointed by chairman Reince Priebus to study the issue.

Ryder’s amendment would create a 13-member committee to sanction a list of approved presidential-candidate debates. Eight members would be elected from the RNC membership — two each from the committee’s four regions — and five more would be appointed by the RNC chairman.

“We would be in control.”

Once a committee so appointed determined on an officially sanctioned list of debates, any presidential candidate participating in an unsanctioned debate would be prohibited from taking part in any further sanctioned debates. All details of the sanctioned debates would be overseen by the 13-member RNC committee — the rules, the questions, the choice of moderators, the length of answer time permitted to the candidate….everything and anything, in short.

“We would be in control,” Ryder said. Not “the Great Mentioner” (presumably meaning the media as a collective entity).

At first, it seemed as if the Ryder proposal would go down smooth and easy. Perhaps without debate. Henry Barbour of Mississippi sprang up to call the idea “a clean and appropriate response to what did not go well in 2012.”

But then some critics materialized, standing and voicing objections. First was Ada Fisher, an African-American committeewoman from North Carolina, who tried her best to sound agreeable but plainly had some doubts. “I’m neither for it nor against it. I’m confused by it,” she said.

Fisher brought up the issue of freedom of speech. She confessed that she didn’t want “to be in a position of telling people” what they could and couldn’t do, and that’s what the amendment seemed to be doing.

She was followed by Diana Orrock of Nevada, who asked for “clarification.” Just what constituted “debate?” Was the term so broad that the amendment really would be a threat to free speech and to the freedom of action of would-be candidates. Plus: “I don’t think punishing people is the right approach.”

Ryder stood up to respond, and in his best courtroom manner —smooth and non-antagonistic but unyielding — set out on a rebuttal. The issue was not about this or that random meeting but only about “sanctioned” debates, he said. And it wasn’t a free speech issue, it was an issue of how the Republican Party selects its nominee “to give our nominee the best possible chance.”

In the last election cycle, Ryder said, the debates “were hosted by a hostile media,” who had “talking points and set up our candidates for damaging sound bites.”

Another objector was Morton Blackwell of Virginia, who more or less concurred with what Fisher and Orrock had said and offered an amendment to Ryder’s amendment. Giving the chairman five appointees of a 13-member body meant too much centralization and gave the chairman too much authority over the body, he said. Why not downsize the committee to the same proportions as most other policy-making RNC committees? That would be 8 elected members, 2 from each of the four regions, and one appointee by the chairman. 9 in all.

Blackwell’s motion was seconded, and, for a while, it looked like there was a real division of opinion. A few other voices of discontent with the proposed new rule were heard. One of them, Charles Curley of Wyoming, conflated de Tocqueville with the Lord Action saw about absolute power corrupting absolutely, but his meaning was clear.

And when Blackwell protested that the rule, with its punishments and restrictions, would treat presidential candidates like “irresponsible teenagers,” he got a burst of generalized applause.

“Somebody has to say No to Candy Crowley!”

All of that turned out to be misleading. A key Ryder ally, Randy Evans of Georgia, rose to acknowledge that his 2012 candidate for president, home-stater Newt Gingrich, had profited from the free-ranging nature of that year’s debates.

But the issue was very simple, he said.”This is about control…the networks versus the party. No more is the mainstream media going to control what we do.” As he had put it earlier, in what was probably the defining line of the debate, a show-stopper, “Somebody has to have the power to say No to Candy Crowley!”

In the end, the objectors to the Ryder amendment turned out to be only a handful, limited essentially to those few who had spoken against it. Blackwell’s amendment to the amendment went down hard, and then Ryder’s amendment sailed through the Rules Committee.

The main body of the RNC would have a chance to vote on the rules change at the spring meeting’s culminating general session on Friday. Ryder confidently predicted that no more than 10 No votes would be mustered against it, and he was probably right. The mood of the RNC was clearly one of rebellion against what members saw as the lying biased manipulators of the media.

What neither Ryder nor any other exponent of the rules change opted to explain, however, was this: If it is indeed true, and not merely an exercise in hyperbole, that “93 percent“ of the media — and presumably “political journalists” were meant — manifest an aversion to Republicanism, then why was that?

Was it truly possible to commandeer so large a proportion of the nation’s journalists into a conspiracy? And, if so, just how was this done, inasmuch as reporters come in all sizes, shapes, and ethnicities and, like all other working stiffs, are hired piecemeal, in their highly diverse and disparate cities, counties, and states? Inasmuch, further, as the hiring is done by equally diverse managements who were often in direct competition with each other?

And if this 93 percent isn’t a conspiracy, if it’s just the overwhelming weight of opinion in a professional population whose work consists of keeping up with current events, then what does that mean?

But what if it isn’t true? All those Mort Kondrackes, George Willses, John McLaughlins, David Brookses, Brit Humes, Paul Gigots, Laura Ingrahams, Sean Hannitys, Bill O’Reillys, Michelle Malkinses, etc., etc., etc, that the TV talk shows and blogs and periodicals seem to teem with, can’t add up to just 7 percent, can they?

The availability in depth of such people is, ironically, one of the reasons that Republicans, if they go ahead with the debate-control scheme and do not meet with an effective boycott by the networks, can probably make a go of it.

To paraphrase a famous line by Robert Browning… or what’s a Fox News for?