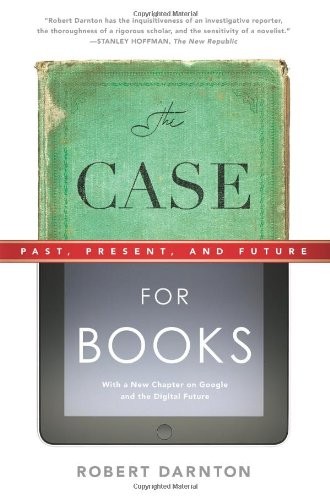

To regular readers of The New York Review of Books and to those who’ve read The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History (which has been translated into more than a dozen languages) and The Forbidden Best-Sellers of Prerevolutionary France (winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism in 1995), one of historian Robert Darnton’s more recent titles came as no surprise: The Case for Books: Past, Present, and Future.

That book is a collection of essays that showcases Darnton’s scholarship and ability to communicate broad ideas in a straightforward prose style for specialists and general readers alike. But the book closes not with answers but on a single question: What is the history of books? That “history” is a field of enquiry Darnton has spent a scholar’s lifetime helping to define.

[jump]

Darnton has been a Rhodes scholar, a reporter for The New York Times, a MacArthur Fellowship winner, and past president of the American Historical Association. Last year, President Obama awarded him the National Humanities Medal. Today, he serves as a trustee of the New York Public Library and as professor and head librarian at Harvard University, his alma mater. He has also been instrumental in establishing the Digital Public Library of America, which allows online, free access to the holdings of libraries, archives, and museums — currently 2.5 million items — for anyone within reach of a computer.

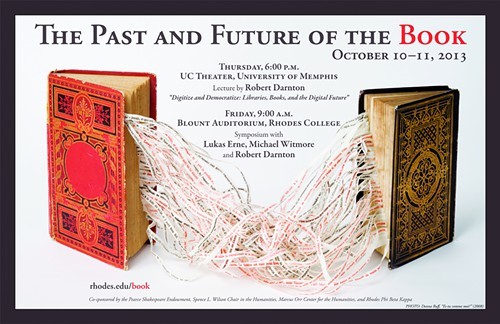

This week Darnton is in Memphis for two events under the heading “The Past and Future of the Book”: a lecture at the University of Memphis on Thursday, October 10th, and a Shakespeare symposium at Rhodes College on Friday morning. Both events are free and open to the public. As they should be for this leading expert on the Enlightenment. The free spread of ideas is, for Darnton, key to a free and just society.

The Flyer spoke by phone with Professor Darnton a few weeks before his Memphis visit. The opening topic: Darnton’s talk on Thursday evening.

Your lecture at the University of Memphis is titled “Digitize and Democratize: Libraries, Books, and the Digital Future.” Care to give us a preview?

Robert Darnton: It may sound tendentious, as if the alternative is between democratizing or digitizing. But they’re not alternatives. The two are complementary. The alternative is commercialization. My talk will deal very briefly with the history of libraries and books, but it will mainly discuss our present situation and where we’re headed.

I think we’re in a period of transition, and we all know the future is going to be overwhelmingly digital. But, meanwhile, analog printing is still going strong. So it’s not that books are extinct. In fact, more books are published each year than the previous year, in the U.S. and Britain and many places.

The issue facing us today is one of access: How in this mixed world of digital and printed media are we going to promote the public welfare, the right of the public to access information? That may sound abstract and unreal, but it’s very real, because there are a lot of commercial operations that want to make money by restricting access.

One of them was Google Book Search, Google’s plan to digitize the world’s books but at a cost to the very libraries supplying the database.

I don’t want to point the finger at Google and dramatize things too much, but Google Book Search did demonstrate the ambition to close off access to knowledge and charge money for it. That was what the Google settlement was all about: The creation of a commercial digital library at an enormous scale, and when the Southern Federal District Court of New York in March 2011 declared that unacceptable, illegal, a violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act, that put an end to Google Book Search.

Enter the DPLA: the Digital Public Library of America.

For the past three years, we have been creating not exactly an alternative to Google Book Search — because we began work before the court made its decision — but a kind of digital library that would make the holdings of research libraries throughout the U.S. free and available to everyone. My talk will be in part a description of that enterprise: the DPLA.

You’ve also written on a topic that may seem, to the general public, an academic issue, but it’s of vital concern to university and research libraries: the huge cost of subscription rates to professional journals. You wrote in 2009, for example, that a year’s subscription to one of those journals cost almost $26,000.

The exorbitant increase in the price of scholarly journals is another form of commercialization. We’ve got to do something about that. The increase in subscription rates is so great that libraries are cutting back in their purchase of books.

Some libraries can “roll with the bulls” for a certain amount of time, but even Harvard, the largest university library in the world, can’t do it any more. We’re going to significantly start cutting back on our subscriptions.

How you resist the pressure of these monopolistic journal publishers requires a real strategy. You can’t just walk into a room and start bargaining. We’ve been doing that for 20 years, and they’re real professionals at it. They’re good at it. It’s not that they’re evil. It’s that they’re commercial. They’re trying to make profits for their shareholders.

If we can get adequate faculty support, we can begin to turn the tide. The positive side of this is the creation open-access journals. A lot of those journals have been founded in the last 10 years, and there’s been a significant trend toward what’s called “flipping,” that is, taking a limited-access journal and turning it around so it’s open-access. That can be done. It’s not easy, but there are ways of doing it.

The DPLA launched in April. What’s been the user response so far?

Terrific. In the first week, we had 3.5 “pings” (or hits) per second.

We launched virtually — that is to say, as an online operation — only because the actual ceremonial opening was to occur on April 18th, three days after the bombings at the Boston Marathon. We were going to have the ceremony at the Boston Public Library in Copley Square, which is across the street from where the bombings occurred.

But so far, everything’s gone very well. The DPLA is in high gear. We’re building up a staff. We have a terrific executive director. More material is being integrated into the system every day. And it’s growing at a good pace. People are committed to it. We have the funding we need. The technology is working perfectly.

No adjustments since the DPLA went online?

Well, there’s been some tweaking. But we spent a lot of time working on the technical infrastructure with top people at what’s called the Berkman Center for Internet and Society here at Harvard. We also had an open competition in which people from all over the country and other countries simply submitted ideas — technological project prototypes. Then we had a blue-ribbon jury choose the top three ideas and integrate them into further development by the Berkman. When the DPLA went online, it really had been tried over and over again. There were no glitches.

There’s been controversy over a Mid-Manhattan branch library in New York City closing and its holdings absorbed by the main public library across Fifth Avenue — the landmark research library that will now serve, partially, as a circulating library. Plus, new, central libraries are being built across the U.S. and the world — architectural showpieces that attract a lot of press. What is the function now and the future of library branches in general?

People tend to think of the New York Public Library as the great library at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street, but the branches are important too but in a different way. They serve neighborhoods, and that service used to be straightforward: That’s where you would go to take out books or read magazines. You could get videos. But over the past few years, we’ve developed lots of special services, which include help with homework for kids in poorer neighborhoods, instruction in English, and a third thing: helping people have access to the internet. That’s turned out to be really crucial for lots of New Yorkers, because newspapers no longer carry want ads for jobs.

But do you see cities and towns pulling their support for smaller branch libraries, thinking readers can simply download e-books?

I can’t prove it by telling you about specific instances. But I do think there’s a lot of what I would call “false consciousness” about the “death” of the book. People are awfully quick to take on this kind of slogan or false truism — that the printed book is out or on its way out and that all information is available. That’s just absurd. It’s not even nearly true.

That’s why I call it a false consciousness, because people buy into it. Some people, however, question it. People in the publishing industry and in the library world know that it’s false. But you can imagine city councils saying: Why spend money on our libraries to buy books that no one is going to read, because it’s all available online?

I do think that public libraries are threatened by that fundamental misunderstanding, and we need to correct it. It’s one of the reasons I now accept invitations to go to places like Memphis in order to spread the word. It’s important that people understand what the actual situation is.

As a historian of the book, you’ve written of the interplay, over the centuries, among publishers, printers, book sellers, book buyers, and a whole host of issues surrounding the production and distribution of printed matter. Do you think such a complex history will one day be written about today’s or tomorrow’s book business?

I honestly don’t know. But there is one thing that’s fair to say: Technological change is so rapid that 10 years from now the information landscape will look very different from the way it looks today. Twenty years … 50 years from now, it will be another world. We can count on change, but what exactly that change is going to be I really don’t know.

You’ve also written extensively on the Enlightenment. What drew you to that period of history?

I’ve spent 50 years studying the 18th century, and people often say to me, “Wouldn’t you love to have lived then and have conversations with Denis Diderot or Thomas Jefferson?” I say I would, but I would have two requirements: one, no toothache, thank you. I’ve spent a lot of time reading manuscripts and letters, and toothache in the 18th century was awful. Secondly, I would rather not be a peasant. And now that I think of it, I’d rather not be a woman, because childbirth was so dangerous.

There’s a lot to be said against the life of ordinary people in the 18th century. But the age of the Enlightenment for me is endlessly interesting — the intellectual richness, the openness of debate.

You hear about America’s founding fathers, and if you’re a 12-year-old, you sort of shrug your shoulders, because it all seems awfully pious — accepted wisdom and so on. But when you read their letters — for example, the correspondence between Jefferson, when he was in Paris representing the new republic, and James Madison, when he was at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 — you’re stunned at the intellectual liveliness of the exchange. In those letters, they’re talking about everything. Jefferson is buying books for Madison. He’s going around the bookstores in Paris looking for bargains and getting the latest thing for Madison. And it went without saying that they could read French. So, the deeper I got into the 18th century, the more interesting it became.

I also think there is a connection between the 18th century and my work at the Harvard Library and with the DPLA, because the ideal of these philosophers of the Enlightenment was to spread enlightenment, that is, to diffuse knowledge. That would happen through the printing press. But in those days only a minority of the population could read and those who could read usually could not buy books. So the printing press, great as it was, was weak compared to the internet as a way of diffusing information.

My view is that we can now realize this utopian vision of people like Diderot and Madison — a vision of the spread of knowledge throughout the entire citizenry, so you could have an informed public and a better republic, a better political system as well.

Has your Harvard appointment left you with less time for your own research and writing?

It’s very busy being head of this library. But Harvard has a peculiar system. It has always named a senior scholar to be the official university librarian, and the idea is not for me to run the library but to deal with policy, faculty relations, fund-raising, general issues. We actually have 73 libraries, and crack, professional librarians do the administration. When I first came here, I did get drawn into a lot of administrative issues, but I’m free of them now. Yes, I teach courses, and I turned in a new book just last week.

And the subject is …

Censorship — a study of the ways censors actually worked: how they did their job, thought about their job, how their assumptions and values fit into the surrounding environment. The book consists of three case studies. One is about 18th-century France, another is about British India in the 19th century, and the third is about Communist East Germany in the 20th century.

The idea is that if you can really get inside these regimes — that is, read the memos and letters exchanged among the censors and between them and the people who ran the governments — you can understand what censorship was. Of course, it was very, very different in each of the three. But then, when you stand back from it all, you ask yourself: What is censorship? That’s part of the point of the book: to rethink the whole nature of censorship itself.

Speaking of, I’m talking to you on Tuesday of Banned Books Week 2013.

It is? I didn’t know that.

Thank you, Professor Darnton.

Thank you! •

For more information on Robert Darnton’s Memphis appearances, go to memphis.edu/moch/events or rhodes.edu/book; facebook.com/Communities.in.Conversation; or on Twitter at @Rhodes_CiC.