I guess I’m in the same boat as this theatre, really. They’ll paint me gold again in three years.

— Robert Plant at the Orpheum Theatre, July 12th

I’ve thought a lot about the nature of celebrity this month. From the global phenomenon that is soccer’s World Cup, to LeBron James’s “Decision” (forever to be capitalized by sportswriters), to last week’s major league All-Star Game, the sports world has managed to out-do its over-hyped self in a matter of a few short weeks. Add Serena Williams at Wimbledon and Tiger Woods at the British Open to the mix, and we have the kind of month that might see the equator wrapped in a red carpet. If you’re not a star, you must certainly be in proximity to one.

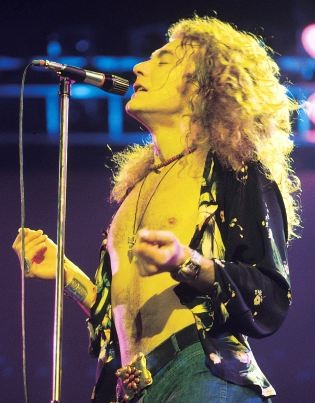

In advance of the opening show of his latest world tour, Robert Plant was honored by The Orpheum last week with a Sidewalk Star. The former front man of Led Zeppelin is the kind of star who could power his own galaxy. Gracious and appreciative in accepting the award from Orpheum president Pat Halloran, Plant accommodated a small media contingent by answering a few questions and seemed, if anything, somewhat bored when the questions were centered on his days with the first (some would argue still greatest) hard-rock band on the planet. Those old enough to remember the Seventies and the impact Led Zeppelin made before downloading and file-sharing became a part of the music lexicon had to be wondering what had become of the Golden God?

And that’s where I find a distinction between the continued star power of Robert Plant as compared with the likes of David Villa, LeBron James, or Albert Pujols, however mind-blowing those athletes are at times. With the Internet allowing 24-hour access to the most mundane “news” item, modern stars — particularly athletes with their legion of followers and fantasy owners — are with us in a way no star could be as recently as 30 years ago. My 11-year-old daughter has seen Pujols play more often than my father saw his hero — Stan Musial — over the entire course of Musial’s 22-year career. Pujols has performed live for Sofia (in an actual ballpark), on a computer screen, and television. She knows him well enough to recognize differences in the way he shaves.

But somehow a celebrity as large — metaphorically — as Robert Plant, coming from the generation he does, is above the reach of every website, smart phone, or satellite feed. This has much to do with Plant’s prime having unfolded just before the dawn of the Information Age. (Though the suggestion of Plant’s prime having been almost 40 years ago would have drawn an icy stare at that press conference. I kept my mouth shut.) There will never again be a band like Led Zeppelin, because there can never be the kind of mystery and global disconnect that made the band so, well, god-like to those first listening to “Dazed and Confused” or “Whole Lotta Love.” A band with equal talent and star power today would be saturated before they could even conceptualize a third album, thrown behind the latest Justin Bieber in the queue of pop-culture consciousness.

Standing 20 feet from Plant as he highlighted the reasons he’s come to love Memphis and this region for its influence on his — and so many others’ — music, I had a hard time connecting the man’s professorial tone with the same vocal chords that made screaming an art form. (Plant, on his own fame: “Is it really such a big deal to be a great singer, or is there something else about all this? It’s to keep changing, and stimulate yourself, no matter what you do, or whom you do it with.”) Which is to say, I had a hard time connecting the star to the human being standing in front of me. Stars of Plant’s magnitude — legends — never die. But humans all do. However many digital images, highlights, or songs celebrities leave behind — and these can now be counted in the millions — what is the lasting memory a person-as-celebrity wants to leave?

Unless you’re a celebrity, it’s an impossible question to answer. The best you can hope for, likely, is to be painted gold now and then.