The past few years have seen the passing away of numerous giants whose imprint on Memphis history (and on human history, for that matter) has been huge, and only the inevitable likelihood of one of them being inadvertently overlooked prevents me from attempting to list them severally.

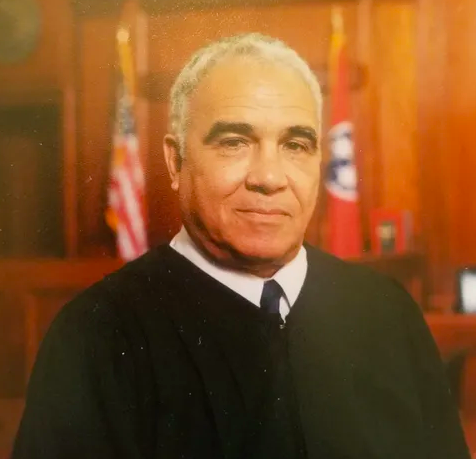

Judge Russell Sugarmon

But Russell Sugarmon, who died Monday in hospice care at the age of 89, takes second place to none of them. At this writing, arrangements for his funeral had not been announced, although his son Tarik, a City Court judge and one of six Sugarmon offspring (several of them influenced by their father’s example to seek public careers) has indicated there will be public rites, probably next week, at Monumental Baptist Church.

Certainly there is no one more entitled to lie in state, and you can be certain that the high and mighty will be in attendance at his last rites, along with enormous numbers of plain folk, white and black, who know that they owe a debt of gratitude to Russell Sugarmon, who did as much as anybody (and earlier than most) to cast off the shackles of white supremacy from his society, thereby making it freer and more just for all.

Though he was first and foremost a hero and champion for his fellow African Americans, Sugarmon was not bashful about owning up to his own mixed ancestry — white, black, and a smattering of Asian as well — and, through all the back-and-forth swings of relations between the races during his lifetime, he was impeccably and absolutely loyal to the ideal of universal equality, as much without prejudice of any kind as it is possible to be.

His interests were accordingly diverse. He was an erudite man with the common touch, and the course of his education ran from Booker T. Washington High School through Morehouse College, Boston College, Rutgers University, and Harvard Law School.

One of the fascinations in his late adulthood was the puzzle of Einsteinian relativity. The study of it occupied much of his spare time after he had settled into a kind of retirement.

But before that happened, he used himself as a battering ram on behalf of justice. He first ran for public office in 1959 as a candidate for Public Works Commissioner under the old commission form of government, a system first imposed upon Memphis by Ed “Boss” Crump and still functioning as a tool of the local power structure in the years immediately following Crump’s death in 1954.

Sugarmon did not win, but he forced the whites in the field of candidates to anoint one of their own, and one only, to remain in the race, giving what was still a white majority in Memphis some assurance that the social order would remain, at least for the time being, inviolate. Though Sugarmon was modest of disposition and by no means a glory-hound, he would become the very symbol of local black aspiration for the next couple of decades and, in 1966, he would win election as a state representative, serving a single term in the Tennessee General Assembly and winning election later as a judge in General Sessions Court.

Sugarmon’s 1968 defeat in the Democratic primary by another aspiring black politician, Alvin King, ironically underscored Sugarmon’s success, along with such other pioneers as H.T. Lockhart, A.W. Willis, and Ben Hooks, in kindling political passions — and competitiveness — among African Americans in Memphis.

None of the eminent and able African-American public servants who followed in his wake failed to see Sugarmon as the pathfinder who did so much to enable their own success. He belonged to all of us.

We — and the entire community — grieve along with his dedicated wife, Gina, and his children Tarik, Elena, Erika, Monique, Tina, and Carol — and extend them our most sincere condolences.