Dismissing wrestling because it’s fake is like criticizing King

Lear for being inaccurate history. Those who do so miss the point.

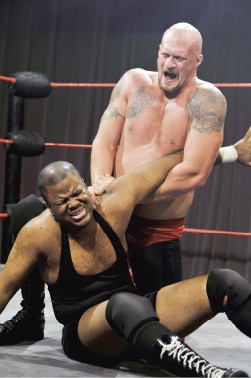

When skilled wrestlers get together, they jam like musicians, pairing

the physical abilities of a gymnast with the responsive skills of an

improv comic. And like an actor playing Lear, the men and women who

step into the ring are motivated by a desire to tell stories about

characters who are larger than life and to put on the kind of shows

that make people want to shout. “It’s a cool feeling to go out in front

of 10,000 or 15,000 people and have them in the palm of your hand and

to be able to stand them up and sit them down,” says Ken Wayne, former

wrestler and founder of the “Nightmare” Ken Wayne School of

Professional Wrestling.

Wayne can list wrestling moves like he is reciting the alphabet:

standing arm drag, hip toss, body slam, locking up, grabbing roll,

alligator roll, hitting the ropes, gut wrench take-down, top

wrist-lock, bottom wrist-lock, hammer-lock, full Nelson, and so on.

Everything in wrestling, he insists, is derived from these and a few

other essentials.

“I have guys come in here and ask, ‘What kind of gimmick can I be?'”

Waynes says. “I say, ‘Shut the fuck up. Learn your craft, and you can

be any kind of gimmick they ask you to be.'”

In a metal shed in a grubby corner of West Memphis, Arkansas, Kevin

Charles, a stout man in his 20s, stoops to pick up a broom. He surveys

the large empty room around him and the wrestling ring at its center,

then with a feline grace at odds with his lumpy physique, he dives

under the ropes, springs to his feet, and begins to tidy up the place.

He dances his broom around the mat with studied purpose and meditative

calm. Friday nights are fight nights at the school. The audience is on

the way, and everything has to be perfect.

Charles, a New Orleans native, is a bartender and National Guardsman

who enrolled in Wayne’s school because he’s always dreamed about flying

off the top rope. He didn’t know if he was the kind of guy who could do

it, but now he believes he is that kind of guy.

He also understands now that when a match is over and the bright

lights dim, the loud threats crossfade into collegial laughter. “Humble

or stumble” is the wrestling fraternity’s guiding principle.

For every student like Charles, there are eight or nine who don’t

make it past the first week of training. Wayne, the son of Memphis

wrestler-turned-promoter Buddy Wayne, blames himself for the dropout

rate. “I anticipated about a two-thirds percent quitter,” he says, a

Kool 100 smoldering in the ashtray near the freshly cracked beer on his

desk. “It’s more like about an 80 or 90 percent quitter. I probably run

a lot of people off because I tell them exactly what it is they’re

getting their ass into.”

Wayne grew up with a wrestling ring in his backyard and has done

just about everything you can do in the business. He’s built rings,

hauled rings, and broken them down. He’s wrestled solo as a

bleach-blond brawler and alongside Danny Davis as half of a scrappy,

masked tag team called the Nightmares. He grew up on the road with his

dad, riding from town to town and from dressing room to dressing room.

He knows what it’s like to hold a championship belt over his head and

to take four Darvons and not feel relief because he wrestled with

cerebral fluid on his spine.

Wayne says he never imagined running a wrestling school when he got

out of the business in 2005. Eight months after retiring, he faced the

realities of being 46 years old, unemployed, and not knowing a thing in

the world but wrestling.

“I didn’t retire; I just quit,” Wayne says. His skills were

slipping. He hurt more than ever, and he could no longer fool himself

into believing that fact wasn’t reflected in the quality of his

bookings. Increasingly, he was matched against wrestlers who were, in

his opinion, poorly trained or not trained at all.

“I didn’t want to be one of those guys who are the last to know that

they should have retired a few years ago,” he confesses. “And I didn’t

want to have a career-ending injury. What sense would that make?”

Wayne never became a WWE superstar, but for a smaller-than-average

wrestler who came of age in the 1980s, when giants were all the rage

and masked marvels were out of style, he pieced together an impressive

26-year career that took him across the United States and Canada and

into Puerto Rico — where air conditioning is scarce and blood is

absolutely expected.

Jonathan Postal

Jonathan Postal

Ken Wayne

“I’ve done all this,” he insists. “I can teach these kids a whole

lot more than just how to do a bunch of holds. They need history. It’s

essential that you know where you came from. And they also need to have

a philosophy.”

Wayne’s school maintains a small but diverse student body of

athletes, nerds, flamboyant personalities, and everyday Joes. At one

end of the spectrum, there are wrestlers like Wayne’s son Eric “3-G”

Wayne, who bills himself as a “third-generation wrestling superstar,”

and 25-year-old Kevin “Kid” Nikels, a 220-pound construction worker

with a bald head, a shoulder covered with tattoos, and the roar of a

Viking berserker. Self-effacing backstage, Nikels describes himself as

a “strong style” wrestler who doesn’t mind getting knocked around.

In the opposite corner are saucer-eyed beginners like D.J. Stegall,

an excitable, pint-sized fanboy of 19 who works for his father at a KFC

in Batesville, Mississippi.

Between the extremes, there are intermediate grapplers like Charles

and boy-next-door-type Dan Jones, an electronics repairman for

Walgreens, who wrestles under the name Dan Matthews.

All of Wayne’s students do have one thing in common: They grew up

obsessed with TV wrestling. Most of them associate watching wrestling

with happy memories of family life. They have nearly identical stories

about bounding off their living-room sofas to put an elbow drop on dad

or a sibling. “Hit him in the balls,” Nikels says with a laugh,

remembering a particularly effective off-the-couch strike against his

old man.

Nikels is a graduate trainer at Wayne’s school. He describes

wrestling as therapy. “Sometimes you have a bad day or you’re stressed

out,” he says. “But once I come in here and get started wrestling, it

goes away. You think about throwing this guy or punching him in the

head. You take out your frustrations and forget about what’s bothering

you outside the room. It’s like going to the doctor’s office.”

Jonathan Postal

Jonathan Postal

Kevin Charles

Nikels originally wanted to be a rock star, but he didn’t have the

guitar chops. “So I figured I should work on getting big and learning

how to wrestle,” he says, describing a period when he trained three

days a week, went to college full time, worked construction full time,

and hit the 24-hour gym after hours. “I got used to sleeping only two

or three hours a night,” he says, rubbing his head bashfully and

laughing at his obsession.

Hard work has paid off for both Nikels and Eric Wayne. Both have

been called into auditions for the WWE and have received positive

feedback. The younger Wayne says he left the audition feeling like he

and Nikels already possess the skills they need to go all the way. “But

you’ve got to stand out,” he explains.

“The WWE is the top notch, so you’ve gotta be top-notch too,” Nikels

adds.

Both take this to mean they need to be bigger, or at the very least

more ripped.

“You have to look like an athlete,” Eric Wayne says. “If you’re 185

pounds and ripped to shreds and you can actually wrestle and you don’t

trip over yourself getting in the ring, chances are you might be hired

and get to the big show.”

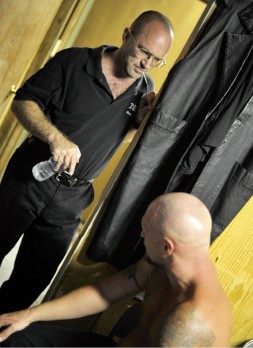

“Size is a big plus, but it’s not the be-all and end-all,” says

Bruno Lauer. Known to Memphis wrestling fans as Downtown Bruno and to

WWE fans as bad-guy manager Dr. Harvey Whippleman, Lauer sits with a

beer in his north Mississippi clubhouse beside an action figure that

looks just like him. Nearby is the WWE women’s championship belt that

he won by dressing up in drag and taking on the KAT in a special

snow-filled ring.

Jonathan Postal

Jonathan Postal

Lauer, a referee and occasional adviser at Wayne’s school, is the

picture of contentment. Today, the self-described “dried-up 120-pound

redneck” works outside the spotlight as head concierge for the WWE, a

gig he describes as “head gofer.” He is thrilled to have beaten the

odds and made a 30-year career in professional wrestling. Lauer

stresses the importance of charisma and credits his own unlikely

longevity to “heart.”

“To paraphrase Gene Hackman’s Coach McGinty in the greatest movie of

all time, The Replacement, [I owe my 30 years in the business

to] heart. Tons and tons of heart,” Lauer says.

“Everybody says professional wrestling is fake,” Eric Wayne says.

“They say we know how to fall and we pull our punches. My reply is,

I’ve knocked out people’s teeth; I’ve broken their orbital bones; I’ve

shattered their knees.”

The young wrestler isn’t bragging and is remorseful for what he

views as an unfortunate combination of poor judgment, circumstances,

and bad luck. He worries that a reputation for being careless and cocky

could hurt his chances for advancement. “When you start wrestling, your

dreams and aspiration are ‘I want to make it to the big show. I’ll do

whatever’s asked of me,'” he says.

“There’s an expression they have backstage [at the WWE],” Wayne

adds. “They say, ‘Humble or stumble.'”

“I’m going for it,” Dan Jones declares during a break in his

Monday-night training. At 31, Jones is old for a wrestling student. He

knows he’s only got about 10 years to see if he has what it takes to

make it in the WWE.

“[My wife’s] the one who told me to go do it,” Jones says. “She saw

how depressed I was just sitting on the couch watching [other people]

do it. She said go do it. Get it out of your system.”

Jonathan Postal

Jonathan Postal

Bruno Lauer and Kevin Nikels

Charles is younger and less driven than Jones. He’s open to the idea

of a professional career but also enjoys wrestling for its own sake.

“You’re not only performing athletically, you’re putting on a show for

the fans,” he says. He calls the complex relationship between wrestlers

and their audience “a new level of professionalism that you really

can’t find anywhere else.”

On Fridays, a little before 7 p.m., a “$5 Admission” sign goes up

near the door, and Wayne’s secluded school on Jefferson Street is

transformed into the high-tech home of New Experience Wrestling

(N.E.W.), a weekly promotion that showcases the school’s graduates and

experienced students.

Wayne and his wife, Debra — also a second-generation wrestler

— stand backstage, working out the show’s technical details.

“Today’s wrestling business, on a national scale, is called ‘sports

entertainment,'” he explains, wondering aloud if fans might be

attracted to a more competitive approach, blending older and newer

styles of wrestling. “We want to show off the athletic abilities of our

performers,” he says.

N.E.W. events also help Wayne’s students learn how to perform in

front of a television camera and provide opportunities for training in

operating audio, video, and computer equipment.

Jonathan Postal

Jonathan Postal

Dan Matthews

As fans take their places in a double row of folding chairs, two

announcers banter, testing their microphones. Camera operators check

their video equipment. Backstage, the wrestlers psych each other up for

the show.

There aren’t more than 30 people in the audience, but when the

lights come up, the N.E.W. wrestlers go at it like there are 30,000

people in the seats. It’s another chance for Eric Wayne to prove he’s a

superstar who isn’t careless; another opportunity for Kevin Charles to

live his dream and for the undefeated “Kid” Nikels to prove he’s still

the baddest man in the building and worth the thousand-dollar bounty on

his head. It’s a big show. They all are.

What most people call bleeding, wrestlers call “getting color.” And,

like the costumes and the trash-talking interviews, it’s all part of

the show. But there is nothing premeditated about the color drawn

during Matthews’ brawl with “Golden Boy” Greg Anthony, his fourth

official fight in front of a paying audience. And the blood was nothing

compared to the distraction of seeing his wife on the front row,

calming their small children, who couldn’t understand why Daddy was

taking what appeared to be the beating of a lifetime.

Jonathan Postal

Jonathan Postal

Debra Wayne

After the match, an upbeat Matthews tells his instructors he won’t

be available for regular training on Sunday evening because he needs

some family time. “It’s my anniversary weekend,” he says

sheepishly.

Ken Wayne voices his approval. “You don’t want to miss your

anniversary,” the twice-married “Nightmare” cautions.

“Well,” Matthews says, walking out into the school’s parking lot,

past a maze of forklift pallets, mountains of sawdust, and shattered

lumber, “my anniversary is actually today.” The other wrestlers laugh

and nod their heads knowingly.

“I’m here at the ‘Nightmare’ Ken Wayne School of Professional

Wrestling, because, basically, it’s my life,” D.J. Stegall says, prior

to a Monday-night class. He might as well be speaking for everyone who

has ever found his way to Wayne’s school and stuck around for more than

a week. Stegall says he’s no longer bothered that people taunt him

because of his small stature, and he doesn’t care what anybody thinks

about his decision to go into the ring.

“I’m not in it for the celebrity status,” Stegall says. “My goal is

to be considered a great wrestler. Whether I get to the WWE or not,

whether I’m wrestling in front of five people or 500 or selling out

Madison Square Garden, I want you to look at me and say, ‘That guy’s a

great wrestler.’ I’m in this for respect and to do what I love.”

Jonathan Postal

Jonathan Postal