In early 2019, Memphis cinematographer Ryan Earl Parker got a call from director James Tovell. “He said, ‘Hey, you wanna go dig up some mummies?'”

Parker, who got his start in the Indie Memphis scene, formerly worked with Tovell on a documentary for National Geographic. This project had the potential to be much bigger. Archeologists searching the Egyptian desert near the sacred city of Memphis had found a tomb that had apparently been untouched for four millennia. It was the biggest find in Egyptology in 50 years. “They basically sold the film rights, and through that process, they were able to pay for the diggers and the scientists to do their work,” says Parker.

In Secrets of the Saqqara Tomb, the diggers and scientists are locals. They’re captured on film by Memphis-based cinematographer Ryan Earl Parker.

In April 2019, with the deep-pocketed backing of Netflix, Tovell and Parker went to Egypt with a small crew to document the excavation in the Saqqara necropolis. The site was less than a mile from the step pyramid of Djoser, the oldest pyramid in the world.

Egyptian archeology has been an obsession in the West since Napoleon’s armies dug up the Rosetta Stone. It also makes good TV, as you can tell from a quick perusal of the History Channel lineup. “The director said, ‘I don’t want this to feel like another BBC documentary,'” recalls Parker. “‘It needs to feel like a movie. I want it to be cinematic.'”

What makes the film Secrets of the Saqqara Tomb special is the access the crew had to the archeologists at work. Instead of a group of talking heads expounding on the burial traditions of the Old Kingdom, Parker’s cameras captured the painstaking process of archeological research, the dusty frustration of an empty shaft, and the joys of discovery as they happened. The diggers and scientists become fleshed out characters. There’s Ghareeb, the serene excavator whose family has been digging in the desert for generations; the ruggedly good-looking Hamda, an archeologist whose smile tells you he’s doing what he was meant to do; and Amira, the anthropologist tasked with reconstructing the bones of the ancients. This is not a standard colonialist narrative of sophisticated Europeans coming to loot forgotten treasures. “These people are all Egyptians. They live very modestly. From a social standpoint, they all understand that these are the remnants of their people. To us, it’s ancient Egypt, but these are their ancestors. They seemed to all have a reverence for that.”

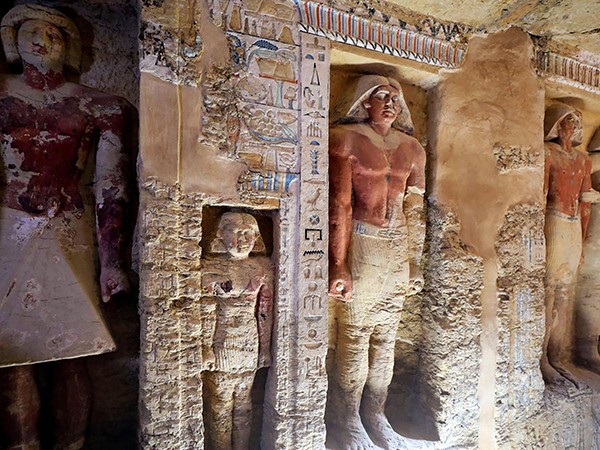

One of the first events Parker’s camera captured was linguists reading the tomb’s hieroglyphs for the first time. The 4,500-year-old text revealed that the owner of the tomb was named Wahtye, and his whole family was buried there. At the same time, the area surrounding the main tomb was yielding rich treasures, such as the first mummified lion ever discovered. “At first, we were like, ‘Let’s set up great frames and let the action just unfold in them,'” says Parker. “But our approach had to change because they were just constantly finding so many things outside the tomb. We just had to go on the shoulder and run to get these shots.”

The climax of the six-week dig was the discovery of Wahtye’s mummy in the bottom of the burial shaft. Parker was looking over Hamada’s shoulder as he carefully brushed away the accumulated dirt of the centuries. “It was a two-and-a-half-foot square,” he says. “I’m crammed in the corner, the camera extended over his body, trying to get shots without disturbing him. I was praying that I was not gonna drop the camera on these old bones. I don’t speak Arabic, so I barely knew anything they were saying. After he had gotten all the bones collected and sent them up, we sort of took a break while we were waiting for the ladder to be dropped down. He turns to me and says, ‘You know, Ryan, you and me were the first to see Wahtye in 4,500 years.’ In that moment, I just sort of stepped outside of myself. You compartmentalize things, you know? I’m a cameraman. I’m looking through the viewfinder. I’m capturing images with all this calculus going on in the back of my head — my focus, my framing, thinking about the edit. But this is beyond me capturing a moment for this project. This is Ryan Parker, country boy from Tipton County, in this moment. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Since Secrets of the Saqqara Tomb hit Netflix last Wednesday, it has captured the imagination of viewers. By the weekend, it was the second-most-watched film on Netflix in the entire world. “It’s on in 190 countries,” says Parker. “What we did is reaching millions of people. I’ve been getting random Instagram messages from complete strangers all over the globe saying they really loved it.”

The key to the film’s success is in how the process of archeology reveals our common humanity. As the anthropologist Amira says while arranging the bones of a teenager who died tragically more than 2,000 years before the founding of Rome, “These people were like us — exactly like us. That is the real story.”

Secrets of the Saqqara Tomb is streaming on Netflix.