Woman, life, freedom — these three words have rallied protesters across Iran after the September 16th death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, who died in police custody after being stopped by modesty police for not wearing her hijab properly. The protests haven’t stopped since. Iranian women are cutting their hair, burning their hijabs in the streets, defying the compulsory hijab law. The death toll continues to rise, but they persist.

Thousands of miles away in Memphis, artist Sepideh Dashti, who emigrated from Iran with her husband in 2011, feels the country’s pain and hope. “This is different. This is really different,” she says. “Like watching it from the news, it’s so inspiring to see all these women in the streets. I really want to be there now.”

Dashti, for her part, echoes the feminist protests in her show “Liminality,” which centers on the feminine body and its paradoxical experience. “Most of my art is about the body,” she says, “because in my country, we were always talking about hiding your body. It’s about control. When you are in public, as a woman, you are not even allowed to smile or laugh.”

“Then I moved to Canada and some people smiled. And I said, ‘What happened to these people?’”

That wasn’t the only culture shock for Dashti, who, despite her background in engineering, pursued an education in fine arts once in Canada. “I remember in this drawing session that they had a nude model. It was shocking for me,” she says. “And at the beginning I couldn’t watch them, even females. My ears were really hot, and then I started to work on myself and started reading about the different waves of feminist theory.”

Over time, themes of feminism began to enliven her work, simultaneously empowering her and invoking anxiety. Outside of Iran, she says, she can speak freely about her contentious relationship with her home country, but there, she has to censor herself. “Maybe they’ll arrest me. I don’t know, but I cannot stop myself from speaking about this.” Despite this vulnerability, she has persisted through the uncomfortable and even invites her audience into this liminal space, where vulnerability is a form of power, a practice of patience.

In a video looped on a gallery wall, a clump of hair grows slowly from the back of a mouth, jutting itself parallel to the tongue, leaving it dry and inciting a similar sensation in the viewer. Inspired by a Persian idiom, Dashti says, the piece symbolizes “waiting for a long time and requesting for freedom for a long time” — so long that having to repeat the same requests over and over again leaves your mouth parched.

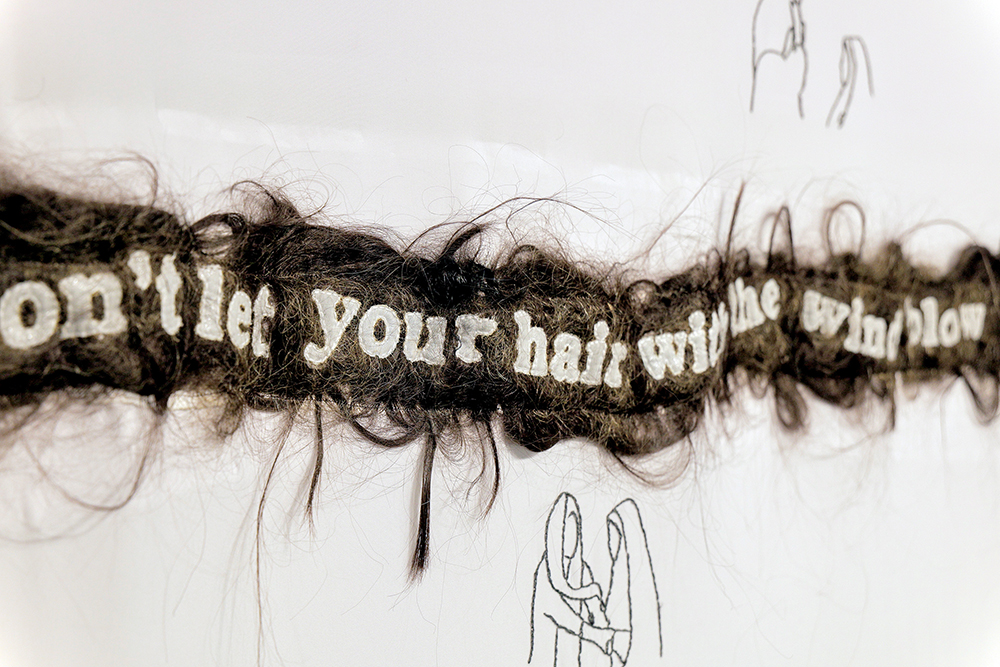

But there is hope that this perseverance will be worth it, that women like Dashti can claim their femininity and Iranian identity with pride. Dashti’s piece Tangled demonstrates this hope, using her own hair and her daughter’s to embroider a grid pattern worn by the Iranian paramilitary, who aim to control women’s bodies, conceal their hair, and limit their self-expression. By weaving herself (quite literally) into this symbol of control, Dashti reclaims this pattern as one representing feminine expression and endurance. She defines the act of sewing as a “feminine action that connects me to the women in my family.” In this way, sewing and, by extension, domestic work takes on a power of its own, a power backed by generations.

In turn, domesticity, traditionally gendered as female, has grounded the artist as she explores her diasporic experience and her desire to find meaning in it. In Under Current, Dashti uses dryer lint to shape continents on a globe. The lint, she says, while representative of the domestic, holds memories of her family. “You can see there are pieces of tissue. I always tell my kids, ‘Do not leave tissues in your pocket,’ but they do.”

In addition to lint, Dashti has attached scraps of metal from beer cans embroidered with wordplay in English and Persian, for instance taking the word “nomad” and separating it into its syllables, “no” and “mad.” The words are scattered across the globe, often with only one visible at a time depending on where the viewer stands, as if lost in a sea of translation yet in the midst of spurring new meaning.

Accompanying this piece plays a recording of found sounds from Iranian protesters, specifically women, throughout the decades, in addition to a reading of Jacques Rancière by her daughter. One sound clip features a young Iranian girl who was arrested by the modesty police, shouting, “Leave me, leave me, let me go.”

“It’s kind of inspired by an essay that talks about male voices being dominant,” Dashti explains, “but female voices are considered noises.” Yet in this show, these female voices are the sounds heard across the world, the chants that beckon Dashti’s nostalgia and activism, the chants that unite woman, life, and freedom.

“Liminality” is on display at Beverly & Sam Ross Gallery at Christian Brothers University through Saturday, October 8th. Sepideh Dashti will discuss her work, Friday, October 7th, noon-1 p.m.