If ever there was a book that’s right in my wheelhouse it’s this bookseller’s memoir. I was sent by God to review it. The Diary of a Bookseller is just that, a sincerely rendered, day-to-day year in the life of an antiquarian bookseller in a small Scottish town. I was prepared to enjoy the particular and peculiar differences between what he does regularly in his used bookstore, across the pond, as compared to what I have done in mine over the past 30 years at Burke’s. But, what I found more interesting is that his days are so similar to mine. His customers could be our customers. His worries are assuredly our worries. His joys are our joys. Even his stock is somewhat similar to our stock, both weighted toward local histories and writers, both a mix of used books and select new books. The similarities pile up; I won’t bore you with others.

It’s hard for me to determine whether or not this book is for anyone who doesn’t work in a bookstore, especially an antiquarian bookstore. But, part of the charm, or at least guilty pleasure of the book, is Bythell’s dour humor and his barbed tongue. He dishes on his employees: “Nicky arrived at 9:13 a.m., wearing the black Canadian ski suit that she bought in the charity shop in Port William for £5. This is her standard uniform between the months of November and April. It is a padded onesie, designed for skiing, and it makes her look like the lost Teletubby.” Or later this, about another: “I have a feeling that ‘outraged’ may well be her factory setting.” He dishes on his customers: “A customer came to the counter and said, ‘I’ve looked under the W section of the fiction and I can’t find anything by Rider Haggard.’ I suggested that he have a look under the H section.”

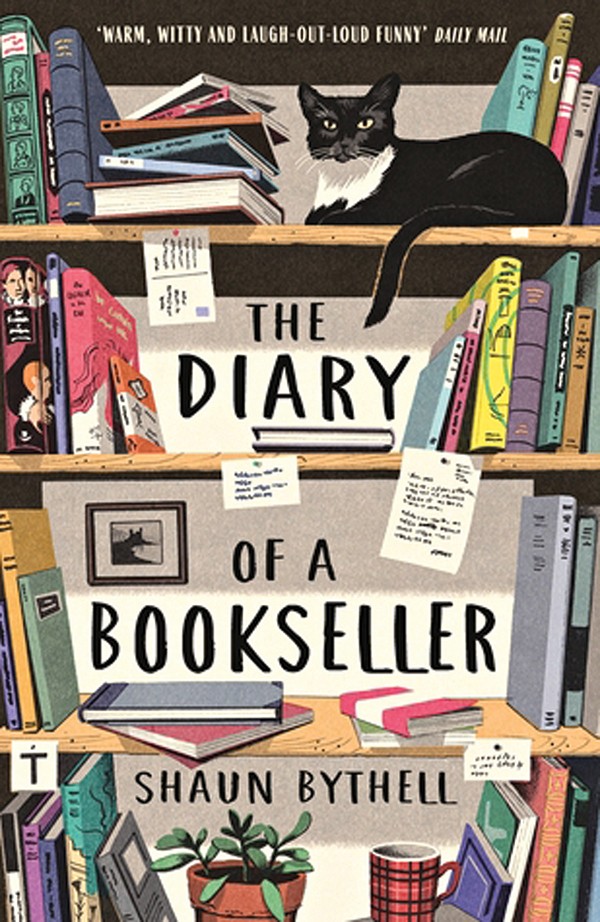

His store is called The Bookshop and it is in Wigtown. His stock is eclectic, everything from cheap Agatha Christie mysteries to pricey and scarce histories from the 16th and 17th centuries. His insights into the buying and selling of used and rare books were as exciting, for this reader, as his sarcastic quips.

In general, in his daily diary, he talks about the books he’s acquired, what he’s reading, the friends he’s made in the business, his partner Anna, his fishing trips, the store’s faulty heating, the estate sales he travels to in search of new stock, and what irritates him. Many things irritate him; his sardonic wit overrides everything. He also notes how many online orders the shop received and how many they were able to fulfill (we do this daily also) and how many customers he had that day and how much money they pulled in. In a singularly British manner, it’s a quaint way to concoct a book.

Of course, working with the public is a constant source of good material for anyone writing a memoir. People are fascinating, ridiculous and sublime, predictably drab or constantly unpredictable, funny and sad, sharp and dull. A year spent noting the passing parade, especially if one is a lively observer, as Blythell is, makes for entertaining reading. Hemingway said, “This looking and not seeing things was a great sin, I thought, and one that was easy to fall into. It was always the beginning of something bad and I thought that we did not deserve to live in the world if we did not see it.” Blythell sees, and he also has a keen waggishness which makes his reflections funny and memorable and this book a hoot.

Finally, it’s also the observation of small, human scenes like this which makes the author a delightful companion through a year of bookselling: “When the old man in the crumpled suit came to the counter to pay for the copy of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, I discreetly pointed out that his fly was open. He glanced down — as if for confirmation of this — then looked back at me and said, ‘A dead bird can’t fall out of its nest,’ and left the shop, fly still agape.”