We’ve witnessed a host of Big Star-themed history in recently years, with box sets, reissues, a documentary film with soundtrack, and the celebrity-laden Big Star Third tribute band, now also documented on film. Lately, that’s when you’ll hear the name Alex Chilton pop up the most. It’s hard to believe there was a time when Big Star was still that obscure group from the long-gone seventies. You were more likely to see Alex Chilton the performer plying his trade at the Antenna Club, or munching on a salad at the Squash Blossom. Back then, that’s just how Chilton wanted it.

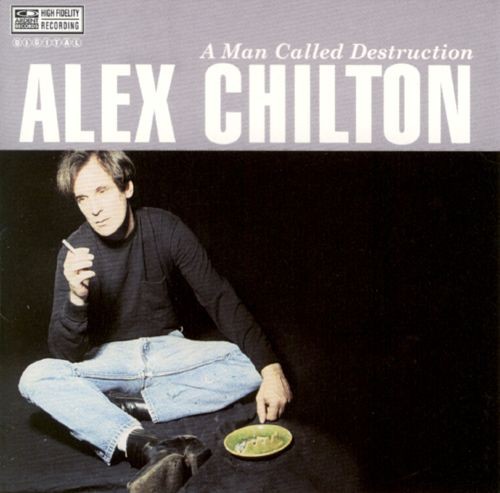

Those years gave rise to a remarkable string of records, from 1985’s Feudalist Tarts EP through 1999’s masterful Set, reflecting a sharper, cleaner, groovier Chilton, with crack bands equally fluent in R&B, jazz, soul, and country, not to mention the kitchen sink. Having seen countless shows from those years, it’s great to again hear one of his finest solo releases, 1995’s A Man Called Destruction, in a new reissue from Omnivore Recordings, to be released this Friday.

Though he had offered up his acoustic take on standards and oddities with 1993’s Clichés, it was a long wait between 1989’s Black List and Destruction for fans of Chilton-the-songwriter. Now, over two decades later, it’s impressive how well the record stands up. As described in Bob Mehr’s deeply-researched liner notes, that may have a lot to do with Chilton’s insistence on recording the band live with almost no overdubs and zero EQ. Such a no-frills approach doesn’t suffer from production trends that can pigeonhole a record in it’s decade for all time. As engineer Jeff Powell told Mehr, “I think he was listening to a lot of jazz at the time, and those records were largely cut live to two-track, and that’s the sound that he wanted.”

That approach pays off: the band jumps out of the speakers, and Chilton’s droll vocals benefit from the dry production. Right out of the gate, you hear the deft interplay of the groove: horns swinging precisely before organ and guitar stabs, over the chugging rhythm section of Ron Easley on bass and either Doug Garrison or Richard Dworkin on drums. The whole affair is loose, funky, and tight, with healthy dollops of Chilton’s bacon fat guitar tones throughout.

Yes, there are several originals here, the standout being “Devil Girl,” where he quips, “Ooh baby, in your cloven flip-flops/Devil baby, power over the jukebox,” before intoning his descending “oohs” with mock foreboding. Featuring the flat fifth-infused soloing in “a revisionist kind of minor” that he so excelled at, it perfectly captures the Chilton spirit of groovy fun. So does his instrumental “Boplexity,” which also has a cameo from Hi Rhythm’s Charles Hodges on organ. Other tracks play it more straight and soulful, yet verging more into hard rocking tones than much of his 80s work.

Song Premiere: Reissue of Alex Chilton’s A Man Called Destruction

The band also shines on the well-chosen covers, many of which were, by 1995, familiar to fans of his live sets, such as the Blackboard Jungle-meets-La Dolce Vita of “Il Rebelle,” the astrological soul of “What’s Your Sign Girl,” the joyously adenoidal “New Girl in School,” the supremely slothful Jimmy Reed number “You Don’t Have to Go,” and more. One cover that ascends to a new realm of originality (which may be true of all these) is the arrangement, crafted by Chilton and saxophonist Jim Spake, of the third movement of Chopin’s “Piano Sonata No. 2 In B♭ Minor,” a.k.a. the Funeral March. Re-imagined for rock band and brass as “It’s Your Funeral,” it takes on a new urgency, charged with both humor and beauty.

Of course, having known this album for decades, all of these delights were like old friends. But what of the seven bonus tracks. For a start, you can hear the world premiere of one them below, a different mix of the glorious “Devil Girl” that features double tracked vocals. It’s good, but it ultimately reveals the wisdom of going for the more stark and intimate quality of the dry vocals that color all of the album proper. Another bonus is the rough mix of the original “Don’t Know Anymore,” which is even more urgent than the track originally included.

There’s another Chilton gem with the soulful “Give it to Me Baby,” but the real standout is another original, “You’re My Favorite,” that miraculously harkens back to his more sordid 70s tracks. A bare track of wiry guitar, bass and drums, with a flip lyric, it recalls the grit of an old track from Bach’s Bottom. Then there’s the only studio version of Chilton’s live chestnut, “(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do,” flubbed lyrics and all. It’s a nice warm up to the triple grand slam: an original, fiercely played blues and the twin run-throughs of “Why Should I Care?” the Funeral March on solo guitar that could have been lifted from Clichés. As with that album, Chilton’s love of classics and standards is in full force, but playfully tossed off; you can almost hear his grin as croons, “Why should I let it get me?/What’s the use of despair/If they call you a square?/You’re a long time dead —Like my old pal Fred./So why, oh why should I bother to care?” By the end, it sounds like an outtake from that old country rube TV favorite, Hee Haw, and you’re reminded of Powell’s reminiscence of the sessions. “There was lots of laughing and goofing around.” When people asked if Chilton was uptight, Powell would just reply, “Nah, man, my stomach hurts from laughing so much.”