A longtime Memphis music insider calls the history of the Memphis and Shelby County Music Commission “labyrinthine.” The organization has existed under different names. It has changed agendas. The doors to the presidency and board of directors seem to revolve at a dizzying pace.

Public perception — insofar as Internet message boards and local-interest blogs can gauge — is that the commission has absorbed ample public funds and produced nothing enduring in return. Plenty of confusion remains, though, about what the commission is actually empowered and financed to do.

When asked how much money the music commission has cost, and to what results, Shelby County finance officer Jim Huntsiger reacts this way:

“That’s a good question,” he says.

Huntsiger explains that the county provided an annual grant in the $150,000 range for operating costs beginning in 2000 but that a scheduled, gradual reduction brought the county government funding to zero as of fiscal year 2008. The city continues to fund the jointly governed organization to the tune of $125,000 annually, while the county’s patience seems to have expired.

Last month, the Shelby County Board of Commissioners voted down a resolution to transfer $50,000 to the music commission for the purpose — in classic music-commission-style vagueness — of “enhancing the music industry.”

With government support waning and a suspicious public looking on, the embattled Memphis and Shelby County Music Commission is at a crossroads.

The music commission and the Memphis Music Foundation, the commission’s fund-raising arm since 2003, split earlier this year. The commission then voted former Motown Records producer Ralph Sutton — who came to the city three years ago to run House of Blues Studio D — its new chairman of the board.

Sutton hopes to adjust the music commission’s focus to the new rules of the music industry, empowering artists with business training and stressing independence — something his experience suits him for. “The most intriguing part of the challenge would be to put what I’ve learned from people like [Motown Records founder] Berry Gordy to work here,” he says.

Standing outside the House of Blues Studio D off Lamar Avenue, Sutton says he is so enamored of his new surroundings that he sometimes records the sounds of the Memphis night. Though Sutton has engineered and produced records by Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, and other giants of the Motown sound, the chorus of cicadas that fills the air after dark in Memphis is new music to the Los Angeles native.

Though the county funds for the music commission have dried up, the city’s share is enough to pay a new executive director. Sutton will participate in that search — the executive director is jointly appointed by the city and county mayors, but the commission board will have some input in the decision — and some insiders say that he needs to look no further than the nearest mirror for the best candidate.

Sutton is game. When asked how he’d do things differently from former commission president Rey Flemings — whose self-interested leadership coupled with the organization’s inertia during his tenure symbolize the commission’s failures in the public mind — Sutton says, “I’ve already been validated.”

Sutton says that certain of the commission’s struggles are attributable to unqualified leadership, mistakes the commission should have learned from. “The press and the public have a right to wonder what the commission was doing,” Sutton says. “The [next] executive director would need to be a true music professional. The city has tried to use a marketing person and a fireman. It has to be someone who has industry connections and the understanding of the creativity and human characteristics of a musician, record producer, or songwriter. It’s important that we select someone who has a running knowledge of the industry.”

While Flemings left the commission for greener financial pastures, Sutton says he’s already been there. “I’m human, and I believe that we’re all striving toward more recognition and better opportunity. I could always go work for Lionel [Richie] or Stevie [Wonder]. But I don’t really have an interest in that. I would prefer to participate in the rebirth of something here.”

It’s simple enough for Sutton to claim greater commitment to the city than Flemings showed, but he views the tasks ahead of the commission with a pragmatism missing from Flemings’ plans, which included bringing the MTV Video Music Awards to Memphis.

“We’re not attractive to major companies right now,” Sutton says. “Sony’s not thinking about coming down here. Universal’s not going to open an office here until we can show them that we have some infrastructure. Industry professionals as a whole need to know this information.”

The rebirth Sutton envisions will require planning for sustained growth and ground-up music industry development built around knowledgeable artists. Sutton says that business-savvy artists enjoy a heightened opportunity to succeed in the independent-driven digital music age.

“People can’t expect us to be able to start doing things like an established city like Nashville,” explains Sutton. “The realistic thing is to recognize that we have things to learn. We need to start industry programs for musicians here. What is a publishing-rights organization [PRO]? What’s the difference between a PRO and a publishing company? They need to know those types of things to know how to make a living. We don’t know who’s going to be a star, but we can help people make a living. We’re in a digital world now, and we have to start with the little things and work our way up.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

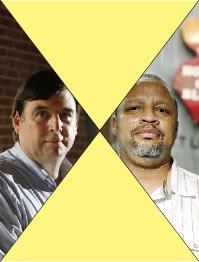

Left: Dean Deyo; Right: Ralph Sutton

Rather than aiming for a one-time big splash like the MTV awards, Sutton defines the role of the new music commission as empowering artists through high-level industry connections.

“ASCAP and BMI would be down here in a heartbeat,” he says. “They wouldn’t open offices, but they’d send high-ranking people to do seminars and Q&A’s. A digital music company like iTunes would love to come and help us with the process of getting our songs on there. We need to learn from Concord and gain from the publicity they’re bringing Stax. They’re the biggest independent record label in the world, and they’re masters of repackaging. They’re showing us how we can do this.”

In the meantime, the commission can still help musicians out in a pinch. They’ve used money from the unused executive director’s salary to subsidize local events like Goner Fest and organizations such as the Center for Southern Folklore. They also administer a health-care program for 15 qualifying music professionals, and they could accommodate more.

Finally, Sutton stresses visibility and accountability for the commission in the local music community. Monthly music-commission meetings take place at the Central Library. “If you’ve got a complaint, come on and say it. If I can’t answer it, then it’s something we’ll have to work on. We need to put ourselves in a position where the musicians can come and access the commission,” he says.

When asked how the commission will be financed after losing its fund-raising apparatus, Sutton says, “That’s going to be another thing. We’ve got to get some real sponsors.”

The organizations — the music commission and the Memphis Music Foundation — have begun to coexist, according to their leaders. “We’re at the front end of getting our relationship back,” Sutton says. “There was some confusion on both sides, but with Dean Deyo’s leadership at the music foundation, it’s getting better. They’re into promoting Memphis music, fostering new artists, and preserving the music. So, if they can do those things, we’re always going to get along.”

“We expect to support things they do, and we expect them to support things we do,” Deyo says.

The Memphis Music Foundation, launched in 2003 as the fund-raising arm of the music commission, split from the commission shortly after Deyo assumed leadership on January 1st. The foundation represents the influence of Memphis Tomorrow, a behind-the-scenes coalition of corporate leaders from the city’s largest companies that encourages economic development here. In 2002, following a series of economic development surveys, the organization targeted three industries as crucial to economic growth in Memphis: logistics and distribution, biotechnology, and music. Memphis Tomorrow formed committees within its membership, focusing on each of the target industries. Phil Trenary, CEO of Pinnacle Airlines, for example, chairs the music-industry development committee.

The foundation came out of the need for fund-raising beyond the $300,000 or so initially approved from the city-county arrangement. Memphis Tomorrow initiated a strategic plan for the music commission, which, in light of personnel changes and the commission/foundation divorce, is the only document available to gauge the organizations’ effectiveness over time.

The plan was based in part on an extensive survey of local music-industry professionals called “Get Loud.” The programs outlined in the plan were to have provided tasks for the commission and foundation. It shows the challenges facing the industry at the time — the lack of professional development opportunities here was cited as the chief obstacle to overall industry growth — as well as a series of proposed solutions, including a Memphis music festival that featured Memphis acts from across generations and genres.

A proposed Sam Phillips Independent Music Center hung its fate on a network of music-industry service “providers” who would donate their time to the center and assist Memphis music professionals. No such providers were identified in the plan, and their recruitment doesn’t seem to have been accounted for.

A proposed Memphis Music Venture Fund never grew beyond the idea that it would include $10 million in assets to invest in worthy local music businesses. Neither did a “music business district” or a Memphis counterpart to the pioneering live-music TV program Austin City Limits. A Memphis “Grand Ole Opry”-style venue, featuring perfect acoustics and state-of-the-art technical infrastructure, located at the corner of Beale and Third, obviously failed to materialize. The plan called for “sponsorships from major electronics manufacturers,” not otherwise identified, to fund the venue.

The strategic plan’s priority schedule rated developing the now-defunct music commission Web site a 10, for highest priority. Likewise, a “global concert event,” a Memphis Music Conference, and something called the “digital distribution initiative” were given top-priority ratings without ever materializing.

Flemings, who was hired in 2003, made an annual salary of $129,950, not including benefits, as president of the combined music commission/foundation. His hiring, insiders say, reflected the will of Memphis Tomorrow and alienated music-oriented members of the commission/foundation board to please the business-minded members. The rift foreshadowed this year’s amicable divorce of the music commission and music foundation, which both organizations deem as mutually beneficial.

The Memphis Music Foundation can now operate privately to promote economic development in the Memphis music industry. “We create talent. It’s just that when we create talent, their attorney is in Atlanta, their studio is in Nashville, and their publicist is in L.A. We want those people here in Memphis,” Deyo says.

While the music commission focuses on connecting local artists to outside resources, the foundation will concentrate on bringing music business to Memphis. “We’re not a foundation to hand out money,” Deyo says. “But if there are things we can do to help with our resources, we’d like to do what we can to help.”

The foundation plans to move into new offices at 431 South Main on October 1st. Deyo says his group can function more effectively without having its books open, like the music commission must do as a public entity.

“If you’re a public body, everything you do can be discussed in public,” Deyo says. “You have to give information to anyone anytime they want it. When you’re negotiating a deal and there’s another city competing for that deal, we don’t want them to know what our deal is.”

Deyo has entered negotiations to bring an independent recording studio to Memphis. He bargains for tax breaks for the prospective business and entices them with other incentives. “We started out against six different cities, and now it’s down to us and New Orleans. I don’t want New Orleans to know what I’m offering, and that’s hard to do when you’re a public body,” Deyo explains.

The potential studio relocation is precisely the sort of project the foundation will focus on in its new incarnation. “Our goal is economic development,” explains Deyo. “In 1973, the music industry in Memphis was the third-largest employer. There were all these different pieces of it that we lost. We want to regain that.”

Deyo says that the foundation will open a musician resource center at its South Main facility to provide up and coming musicians with “knowledge, networks, and connections,” he says. “We’re not going to start a record label. We’re not going to do anything but provide them with a place where they develop a marketing brochure for a band, talk about legal needs, or ask any question about the music business. We’ll provide answers. We won’t tell them what to do, but we’re going to give musicians access to the knowledge of how other bands who have made it have done it.”

In order to establish the music business in Memphis, the foundation must first establish the legitimacy of music and the opportunity it represents to the business community at-large.

“Memphis music is well thought of outside Memphis,” Deyo says. “I couldn’t raise 50 bucks in Memphis today to fund a music business. The business community considers it risky and not for any particular reason. It’s just kind of an attitude. My background with Time Warner helped me build relationships with CEOs of companies here. Part of my job is to rebuild the credibility of the music industry in the eyes of the business community.

“There is a lot to do. I don’t know if we will ever get back to where we were in 1973. That’s pretty heady stuff. I see it as something we don’t have to build from scratch or reconfigure our education system for,” Deyo says. “It can be part of the city’s economic engine and provide jobs.”