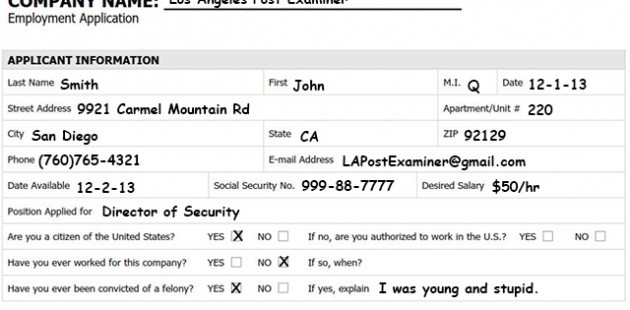

On state job applications, one question can make or break a person’s ability to even get a shot at an interview: “Have you ever pleaded ‘guilty’ or ‘no contest’ to or been convicted of a crime?”

State lawmakers recently passed a bill that would require state employers to drop that question from the initial application for most state jobs. The “ban the box” bill, sponsored by Sen. Sara Kyle of Memphis, passed the state Senate earlier this month and the House this week.

“The problem is those applications are frequently tossed in trash cans before [the applicant] can even get the opportunity to explain [their charges],” Kyle told her follow senators when the bill was being considered on the Senate floor earlier this month. “This bill will help get their foot in the door and help the employer hire the best candidates based on their qualifications and not their past.”

Though both the Senate and House bills drop the question from the initial application, the employer would still have the right to ask about a person’s criminal history during the interview process. But Just City’s Josh Spickler says this seemingly small change can make a big difference.

“Now they’ll have a chance to explain this blemish on their record, and they can also explain why they would make a good employee despite that,” Spickler said.

According to the bill, state employers now must consider how an ex-offender’s charge would affect the duties of the position, the amount of time that’s passed since the conviction or release from prison, the seriousness and frequency of the offense, and the applicant’s age at the time the crime was committed.

“Covered positions” — those state positions that require federal background checks, such as jobs with the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation — are to be excluded from the law. So would jobs with contractors and subcontractors working with the state, political subdivisions of the state (such as county jobs), and positions with the State Board of Education.

The move has potential to help people who may not be able to expunge their records due to the nature of their crime or their financial situation. The nonprofit Just City helps people who qualify for expungement when they can’t afford the $450 fee, but Spickler said his group can only help so many people with the resources they have. And he said expungement is only available for those with certain convictions on their records.

“In Tennessee, the majority of convictions are not erasable. The ones that are are very low-level E felonies and misdemeanors, non-violent first offenses,” Spickler said.

“Ban the box” ordinances help restore dignity for people whose past actions have prevented them from finding work, Spickler said.

“There’s a common misperception that people who have been involved with the criminal justice system don’t want to work, like they just want to sit around and smoke crack or pot all day,” Spickler said. “But there is dignity in work and in taking care of oneself and one’s family. You’re worth something if you can do something that someone will pay you money for.”

In 2010, the city of Memphis passed a similar “ban the box” ordinance for applicants of city jobs, but Shelby County has not followed suit. Despite the fact that the state is considering banning the criminal history question from its own applications, lawmakers just passed a bill that would prevent local governments from expanding their “ban the box” ordinances beyond their own direct hires.

For example, the Memphis City Council can not pass more expansive measures to require subcontractors to ban the box.

“It’s like the state saying, ‘Sorry, we know better than you, so you can’t do anything further than what you’ve already done’,” Spickler said.