Adobe Stock

Adobe Stock

Less than a week after the execution of Nicholas Sutton, the Tennessee Supreme Court has issued execution dates for two more inmates later this year, prompting one anti-death penalty group to refer to Tennessee as the “outlier” in its use of executions.

The court issued execution dates for Bryon Black and Pervis Payne Monday.

Black, a Davidson County resident, was convicted of the 1988 murders of his girlfriend Angela Clay and her two daughters. Payne, a Shelby County resident, was convicted of the 1987 murders of Charisse Christopher and her 2-year-old daughter.

Prior to the court’s order, Black attempted to have his death sentence commuted, citing his intellectual disability. Black argued that his execution would violate both the U.S. and Tennessee Constitutions due to his mental illness.

According to court documents, Black also asserted that the death penalty is racist and that Tennessee “is out of step with the evolving standards of decency.”

[pullquote-3]

The court denied his request, as there were no “extenuating circumstances” that warranted the commutation of his sentence.

However, the court has granted Black the opportunity for a competency hearing in July, which will determine if he is competent enough to be executed. If Black’s petition is denied, his death sentence will be carried out on September 24th.

Payne also asked the court to commute his sentence, citing reasons similar to Black. In addition, Payne asserted that he has a “strong case of actual innocence.” But the court also denied his request. Payne is set to be executed on December 3rd.

Last month, the Tennessee Supreme Court also set execution dates for two more inmates — Oscar Franklin Smith, who was convicted for a triple murder in 1989, and Harold Wayne Nichols, who was convicted for a 1988 rape and murder.

‘Outlier’

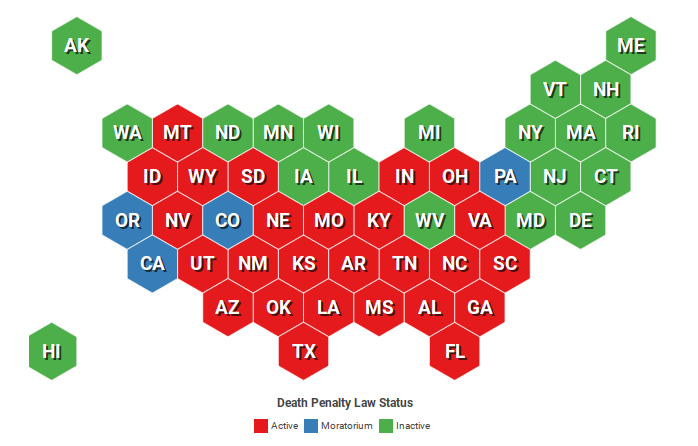

Tennessee is one of 30 states where capital punishment is still legal. Twenty states and Washington D.C. have abolished the death penalty.

Between 2009 and 2018, no executions were carried out in the state. Since August 2018, seven inmates have been executed in Tennessee.

In that 18-month period, Tennessee executed the second-highest number of inmates behind Texas, which carried out 24 death sentences, based on data from the Death Penalty Information Center.

In the past decade — despite an eight-year period of no executions — Tennessee has put the 11th highest number of inmates to death.

Texas tops that list, having carried out 122 death sentences since 2020. Behind Texas is Florida with 31 executions, Georgia with 30, and Ohio with 23.

Death Penalty Information Center

Death Penalty Information Center

States with capital punishment

Stacy Rector, executive director of Tennesseans for Alternatives to Death Penalty, believes Tennessee has become “an outlier in its use of executions.”

Rector notes that the death penalty and support for the death penalty are at “historic 40-year lows.”

[pullquote-1]

“In the most recent Gallup Poll, 60 percent of Americans now say that they prefer the sentence of life without parole over the death penalty, and Tennessee juries have delivered only two new death sentences since 2013, showing that Tennesseans have moved away from the practice,” Rector said. “Increasingly, evidence demonstrates that our death penalty system is not applied fairly and accurately.”

Rector also cites a recent study published by the Tennessee Journal of Law and Policy that concluded the state’s capital punishment system is a “cruel lottery” that is “riddled with arbitrariness.” The study examined every first-degree murder case in the state since 1977 to determine whether or not the arbitrariness that led the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972 to declare the country’s death penalty laws unconstitutional is still a factor in Tennessee.

Specifically, the study concluded that in the more than 2,500 cases reviewed, the facts of the crime could not be used to predict whether or not the death penalty would be imposed. Instead, the study found that arbitrary factors, such as the race of the defendant, the quality of defense, and the views of the prosecutors and judges were the best indicators of whether or not the defendant would be sentenced to death.

Rector agrees, saying that mental illness, intellectual disability, racial bias, and ineffective counsel all play a role in the cases of inmates who are currently scheduled for execution in Tennessee.

Death Penalty Information Center

Death Penalty Information Center

Methods

Tennessee is one of nine states where execution by electric chair is legal. However, no state other than Tennessee has used this method since 2013. Per state law, Tennessee inmates sentenced to death prior to 1999 are allowed to choose between lethal injection or electrocution. Of Tennessee’s seven executions since 2018, five, including the most recent execution of Sutton, were done by electrocution.

Many states, most recently Georgia and Nebraska, have abolished the use of the electric chair, ruling that it is “cruel and unusual punishment.”

There is ongoing litigation surrounding Tennessee’s lethal injection protocol, which some have called “tortuous.”

Most recently, Smith, who is scheduled to be executed this summer, along with four other death row inmates, filed separate federal lawsuits presenting new evidence challenging the state’s three-drug lethal injection cocktail, which was adopted in early 2018.

The three drugs include midazolam, a sedative; vecuronium bromide, a paralytic; and potassium chloride, which stops the heart.

[pullquote-2]

Smith’s lawsuit alleges that midazolam is unsuitable for executions and that there have been problems with the preparation of potassium chloride that the state was aware of but failed to disclose to the inmates or the court.

The suit includes an August 2019 email exchange between prison officials that indicated the potassium chloride was not mixing correctly.

The incorrect mixing of the three drugs can lead to a painful injection, described as “injecting rocks into the veins,” the suit cites. As a result, the drug meant to stop the heart might not circulate properly, and the inmate would die from suffocation.

In 2018, in response to another lawsuit brought forth by 33 death row inmates, the Tennessee Supreme Court ruled that there was no evidence that the protocol constitutes cruel and unusual punishment and that the inmates who brought the suit failed to prove the drug cocktail creates a “demonstrated risk of severe pain.”