“You ain’t so special. Is alive, the Pinch, with people used to be dead.”

That’s Pinchas Pinsker talking to his nephew, Muni, who was beginning to feel like a spectacle, what with everyone in the Pinch wanting to see the new arrival. Thanks to his uncle’s help, Muni’s made it to the Jewish neighborhood north of downtown Memphis after crossing Siberia — where he’d been held for his anti-czarist sympathies — on foot.

Muni and his brethren were hardly the first Jews to arrive in Memphis. Nearly 400 years before, Rodrigo (born Ruben) da Luna of Portugal was one of the small army of men led by the conquistador Hernando de Soto, who was in search of cities of gold. But Rodrigo wasn’t a lancer or musketeer. He was a tailor. How do we know all this? Because Muni Pinsker went on to write about Rodrigo in his chronicle called The Pinch. It’s where we read the earliest known instance of what would become a Memphis trademark: its entrepreneurial spirit. For a fuller description of the enterprising and peace-loving Rodrigo, go to a brand-new book, also called The Pinch:

[jump]

“The author Pinsker chronicled the moment when the rapacious conquistador, sitting astride his Barbary steed atop the Chickasaw Bluffs, looks across the broad expanse of the river that separates him from the golden cities; while from the ranks Rodrigo da Luna is thinking you could go farther and fare worse. He would have liked to try and trade with the natives — maybe swap a starveling mule for fresh fish and persimmon bread — rather than slaughter them as his captain preferred. He thought that maps made a more enduring means of marking a trail than de Soto’s method of paving it with corpses. And wasn’t the real estate atop these rust-red bluffs eminently well situated for civilized habitation? After all, what was to keep the indigenous folk, once they pointed their weapons in another direction, from becoming the tailor’s devoted clients? (“Allow me to custom-fit you for a nice suede breechclout.”) But already the soldiers and carpenters were constructing the barges that would ferry them across the river, and rather than be left behind, Rodrigo da Luna would travel with them into an even more hostile landscape and obscurer death.”

A landscape more hostile? Rodrigo should have stuck around the Chickasaw Bluffs another 300 years.

The year was 1878: That’s when Pinchas Pinsker, himself an enterprising man, arrived in Memphis — or what was left of it. Pinchas, a peddler, had traveled from the Russian Pale of Settlement, to the Lower East Side of Manhattan, to Cincinnati, to Kentucky, down to Tennessee, where he was stopped by a soldier at a small bridge leading into Memphis, a city people were fleeing.

“What bidness you got in Mefiss?” the soldier asked Pinchas.

“Iss to make a livink, mayn beezniz,” Pinchas replied.

The soldier let Pinchas pass — right into a town in the middle of a yellow fever epidemic. But Pinchas survived after being mistaken for dead. He married the Irish girl who nursed him back to health. He established, on North Main Street, Pin’s General Merchandise. And so, to repeat:

“Is alive, the Pinch, with people used to be dead.”

Lenny Sklarew isn’t dead. But Lenny’s head does take a beating from police when he gets caught up in the riot that erupted during a march in downtown Memphis led by Martin Luther King Jr. The year is 1968, the city’s sanitation workers are on strike, and one of Lenny’s legs gets broken too. It wasn’t broken because of police action. It was because the stretcher Lenny was strapped to flew out of the ambulance carrying him to the hospital, and that stretcher traveled west down Madison and into oncoming traffic.

Lenny survives. He returns to his day job: working inside a dusty, rarely visited used bookstore on North Main — same location as Pin’s General Merchandise. But Lenny is doing his own bit in the spirit of entrepreneurship: He sells drugs to the bohemians inside the bar across the street in this once-thriving, now derelict neighborhood known as the Pinch. How do we know all this? It’s in The Pinch, but it isn’t The Pinch by Muni Pinsker (or is it?). It’s The Pinch (from Graywolf Press) by novelist (and native Memphian) Steve Stern.

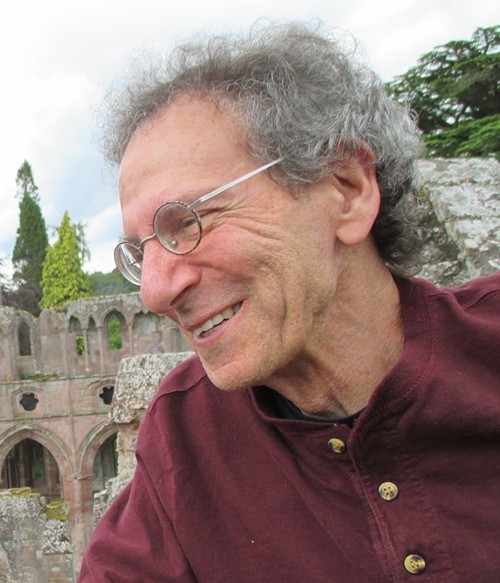

Stern will be reading from and signing The Pinch (subtitled “A History”; sub-subtitled “a novel”) at Burke’s Book Store on Thursday, June 4th, from 5:30 to 6:30 p.m. And it will be a challenge — a challenge on Stern’s part to pick what to read from this very crowded and enormously entertaining novel (or is it a history?).

And like the city where it’s largely set (Siberia at its worst is one major detour), The Pinch comes with its own trademark. Make that trademarks, because for this gifted author — who has written about the Pinch throughout his writing career — there are plenty of stylistic markers: convoluted but masterly storytelling, eye for the tiniest but telling detail, raucous good humor, and an imagination often spilling over into mysticism. All of that in addition to the resilience of a people, which Stern captures down and across the ages.

Time itself in The Pinch? It’s as elastic as a rubber band, as twisted as a Mobius strip, with events far apart in time sometimes chronological, sometimes simultaneous. And for readers: It pays to take your time, because the bigger story in Steve Stern’s The Pinch, which can seem ever about to end, is, as with God and his relationship to his chosen people, really something else: never-ending. •