The attorney for the Memphis City Council said that the city will continue to push for the relocation of the remains and statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest from the Health Sciences Park in the Medical District.

Attorney Allan Wade said that the Tennessee Historical Commission failed to properly adopt the criteria of the Tennessee Heritage Protection Act of 2013, which was used to deny the city’s application for a waiver that would allow for the relocation of the statue and remains of the Confederate general, slave trader, and Ku Klux Klan founding member.

“The commission’s denial of the city’s petition was invalidated due to the failure of the commission to adopt the criteria used to deny the petition in accordance with the Tennessee Administrative Procedure Act,” Wade said.

The commission must now start from scratch and properly adopt criteria, Wade said, which could take until June. Meanwhile, city officials have filed a petition that identifies the grounds for voiding the commission’s decision to deny Memphis’ waiver application.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

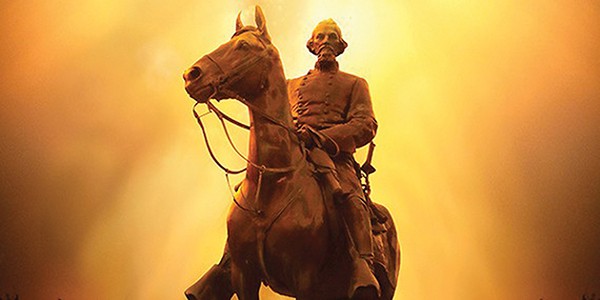

The Nathan Bedford Forrest statue in the Medical District

Commission chairman Reavis Mitchell said in a meeting last year that the city’s application for the statue’s removal was submitted on March 7, 2016, five days before Gov. Bill Haslam signed into law the Tennessee Heritage Protection Act of 2016. Therefore, he said, the application fell under the 2013 version of the law.

Also, Mitchell said that the commission adopted the updated waiver criteria. The city’s petition to the commission states otherwise.

The controversy over renaming and relocating Confederate-themed parks in Memphis began in 2013, when city council passed a resolution to rename three city parks before the Tennessee state legislature could pass measures to prevent such efforts.

Public pressure to remove Confederate symbols on public grounds began to swell across the Southeast states after the racially motivated killings of nine black parishioners in a Charleston church in 2015.

That pressure hasn’t waned completely. The U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals recently gave the city of New Orleans the go-ahead to remove statues of Confederate leaders Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee. The same court is also expected to eventually issue an opinion on the Confederate battle flag portion of the Mississippi state flag.

Forrest and his wife, Mary, were originally buried in Elmwood Cemetery alongside Forrest’s biological brothers and fellow officers in their family plot. That plot is still partially vacated to this day should the remains be relocated back to their original burial site.

Though the Forrests’ wishes were, according to his will, to be laid to rest in Elmwood, two civic groups in Memphis advocated for a reinterment of he and his wife to the newly established Forrest Park in 1905.

Charles McKinney, associate professor of history at Rhodes College, said that historical documentation points to the multiple intentions behind the statue’s erection, the least of which not being a pointed reminder to the growing black middle class, now two or three generations removed from slavery.

“Forrest’s relocation to the center of town was an explicit reassertion of white supremacy,” McKinney said. “It was an act that put a growing black community on notice that both its presence and progress would be greatly contested.”