The sun is shining, the birds are chirping, and the bugs are buzzing. Yep, it’s still summertime, and we’re sure that you’re all tired out from the plenty of summer and staycation activities we’ve thrown your way over the past couple months. So what better time is there to plop down on the patio (or, preferably, a nice air-conditioned room) and crack open a new (or old) book? Read on for some of our 2023 recommendations.

The Slough House series, Mick Herron

I’m not entirely sure how I fell into the world of Slough House, but I’m glad I did. It’s an eight-book series by British author Mick Herron about a bunch of losers from MI5 (the British CIA, basically) who’ve been banished to a decrepit office building in a crumbling London neighborhood.

The building itself is called Slough House, and its denizens are a group of agents with one thing in common: They’ve screwed up their careers so badly that they’ve been assigned to an obscure outpost where they can’t do any further harm to the country’s intelligence operations. Maybe they had a drinking problem or botched a critical operation or fell victim to vicious inter-office politics. They’re called “slow horses,” and each of them wants nothing more than to redeem themselves and get out of Slough House and back into the action.

They are led by the mysteriously competent — and notoriously gross — Jackson Lamb, who somehow has managed to retain a bond to MI5’s leader, Diana Tavener. She has a habit of surreptitiously using Lamb and his slow horses for off-the-books ops, and messy complications always ensue.

The horses are a colorful crew of characters, all flawed, but in ways that make you care about them. But don’t get too attached because Herron seems to have no problem with offing one of his central figures, only to replace them in his next book with someone just as weirdly interesting. He keeps enough of his central core of actors that each book offers familiar protagonists, as well as a quirky newcomer or two.

The plots are all over the place, and in a good way: kidnappings, murders, double agents, assassinations, international intrigue, betrayals of every kind. You never know who you can trust. Herron is a master storyteller with a flair for humor that he occasionally slips in like a dagger in the night.

It’s an eight-book series, and yes, I read them all. Herron has been called the “John le Carré of this generation,” and that’s high praise, indeed, but Herron is much more readable — addictive, even. Start with the first book — Slow Horses — and I bet you’ll be moving on to the second one (and third) in no time.

— Bruce VanWyngarden

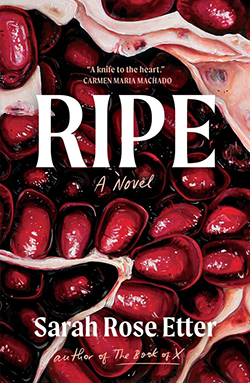

Ripe, Sarah Rose Etter

I’ll admit I wasn’t in the best of moods on April 29th. It was raining, and my friend was already an hour late for meeting me at the Cooper-Young Farmers Market. So I retreated to Burke’s Book Store, where it was dry and where I knew my mood would be lifted. As it so happened, April 29th was Independent Bookstore Day, and right at the store’s entrance was a big ol’ pile of free books as part of the day’s party favors. This, I knew, would redeem the day. After what felt like an hour, I finally found the free book I’d be taking home with me: an advanced reader’s copy of Ripe by Sarah Rose Etter, set to come out July 11th.

The book’s cover, the juicy insides of a pomegranate, caught my eye initially. (Okay, I judge books by their covers, sue me.) But what really drew me in was the first sentence: “A man shouldn’t be seen like that, all lit up.” And then I couldn’t help but read the second sentence and then the third and then the next and the next — okay, I practically started reading it on the spot, probably standing in the way of other book-lovers looking for their own free book. I didn’t care that my friend was now two hours late (?!); I just wanted to sink my teeth into this novel. And soon, I did just that — sunk my teeth right on in and tore through the pages, all of them, in one day.

A character-driven novel at its core, Ripe follows a 33-year-old, disillusioned Cassie, whose most loyal companion is a black hole that never leaves her side — an obvious nod to the depression, anxiety, and loneliness that enrapture the main character. A year into what should be her dream job at a Silicon Valley startup, Cassie is stuck — stuck in a fruitless romance, stuck in an unsatisfying job and hustle culture, stuck in a city where obscene wealth and abject poverty persist. When her job begins to push her ethics and she finds herself pregnant, she must choose whether to remain stuck and whether to be consumed by the black hole that follows her.

Throughout this contemporary novel full of deep and unusual reflections, Etter’s strikingly raw and vulnerable writing weighs on the reader as she explores our late-capitalist society through a dystopic lens. A master of rich imagery and language, Etter hasn’t created a “happy” book but instead an immersive book that crawls under your skin and tugs at your very being.

— Abigail Morici

The Philosophy of Modern Song, Bob Dylan

“One of the ways creativity works is the brain tries to fill in holes and gaps,” writes Bob Dylan in The Philosophy of Modern Song. “We fill in missing bits of pictures, snatches of dialogue, we finish rhymes and invent stories to explain things we do not know.” Not only is it a fundamental principle in both songwriting and song listening, it’s an apt description of Dylan’s own songs. He makes no bones about borrowing from this or that old blues tune, at times functioning more as a curator of phrases and riffs, arranging them in inventive, thought-provoking ways.

This richly illustrated book is built on the same principle. Despite its treatise-like title, potentially offering some stuffy rubric or taxonomy, the 66 essays here, each centered on a song by another artist, whether popular or obscure, are instead a kind of pastiche, a quilt of impressions, imaginings, and history, and a celebration of the way a song can spark a listener’s creativity. Only then, with Dylan’s flights of fantasy, fiction, and fandom established as the modus operandi, will the author occasionally offer an observation on songcraft as an aside.

The end result is not unlike a Bob Dylan album, bubbling over with snatches of traditional verse, noir scenarios, archaic pop-culture references, semi-Biblical metaphysics, and the same down-home vernacular that’s peppered his language since his first Beat-flavored liner notes. “My songs’re written with the kettledrum in mind,” he wrote in 1965, “a touch of any anxious color. Unmentionable. Obvious … I have given up at making any attempt at perfection.”

That impulse to avoid the definitive, perfect statement in favor of walking the listener through a gallery of images and dramas, all via a cultivated plain-speak that still echoes Woody Guthrie, is alive and well here. As one reads it, remember that Dylan won the Nobel Prize as a writer of fiction. Like any novelist, he inhabits the characters in each song until they become “you,” as he riffs on where you’re coming from, walking you through whole worlds suggested by the song like a figure in a dream. This, too, emphasizes the creativity inherent in the simple art of listening. “Take any lyrics and run with them,” Dylan seems to say. “Here’s one story they might hint at.”

While any song’s essay might reference a dozen other songs by way of making a point, Dylan’s no completist. The typical reader of Songwriting For Dummies won’t find chapters on Lennon and McCartney, John Prine, or many others typically revered in the pantheon of songwriting. No, this author is following his own path, dropping bread crumbs as he goes. Take it far enough and it adds up to a full meal.

— Alex Greene

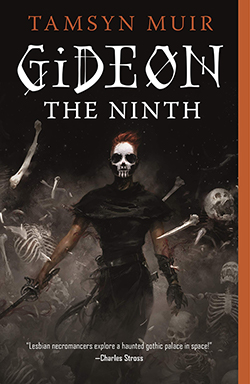

Gideon the Ninth, Tamsyn Muir

Is it too quick to judge a book by its cover, even if it looks pretty dang cool? Ok, well if that’s a bit too fast, maybe the first line of Tamysn Muir’s Gideon the Ninth might be best to clue readers in as to what’s coming: “In the myriad year of our lord — the ten thousandth year of the King Undying, the kindly Prince of Death! — Gideon Nav packed her sword, her shoes, and her dirty magazines, and she escaped from the House of the Ninth.” Coupled with Gideon’s portrait on the cover, clad in black, adorned in skull face paint and sunglasses, and with her sword scattering skeletons to and fro … buckle up.

I was a couple years late to the party, but the first book in The Locked Tomb series was sold to me by friends via an intriguing hook: lesbian necromancers in space. Gideon is a speck in the Dominicus star system, comprising nine planets that are each home to a Great House well-versed in the arts of necromancy, all of whom are in service to the Emperor/Necrolord Prime. Gideon is an indentured servant to the Ninth House, a death cult with an eternal mission to guard a locked tomb that supposedly imprisons the Emperor’s greatest enemy. One of two children at the House, Gideon is constantly menaced by her chief tormentor and heir to the Ninth, Harrowhark Nonagesimus, until a surprise summons comes from the Emperor. He’s in need of new Lyctors — powerful and immortal necromancers — who essentially serve as his lieutenants in wartime.

There’s certainly some table setting that needs doing, but of course, Gideon and Harrow find themselves as the two representatives of the Ninth House, whisked away to the isolated Canaan House with pairs from the rest of the Great Houses (so many houses), and then the real fun begins.

Muir blends her various schools of necromancy into a deep-space take on gothic horror, but the fright is constantly alleviated by Gideon’s brash and foul-mouthed perspective, moments of tension punctured by cursing, dirty jokes, or a passing infatuation with one of the other female House representatives. It really brings a refreshing take on fantasy and sci-fi adventures, blending a light touch of political machination alongside the darker instances of violence and body horror that come with the necromantic territory. There’s a slowly simmering tension underneath it all, with the ten participants expected to pass a series of tests to qualify as a Lyctor. But there’s no exiting Canaan House once the trials have begun, and something else lurks in the shadows, picking off representatives one by one.

There’s a constant drip of psychological and supernatural horror throughout Gideon the Ninth, mixed in with a steady helping of isolated-murder-mystery-induced dread, and plenty of snarl, raunch, and snark to spare. The anxious claustrophobia snowballs as the novel really picks up pace, and I’m not sure there’s anything quite like the cocktail that Muir mixes up here (at least not something that I’ve read). So if you’re eager for a bone-crunching good time, the first Locked Tomb book won’t disappoint.

TL;DR: Lesbian necromancers … in space!

— Samuel X. Cicci

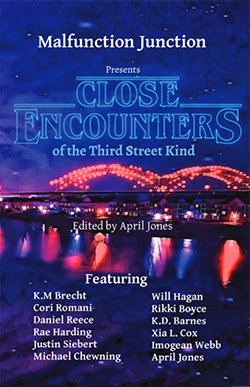

Malfunction Junction Vol. 2: Close Encounters of the Third Street Kind, various authors

In January of last year, I wrote about a group of eight local writers who collaborated on a collection of short stories. The collection, titled Malfunction Junction, contained 15 stories, covering a range of genres, but all set in Memphis. In a way, they were love letters to the Bluff City. For their work, the authors earned Memphis Public Library’s first-ever Richard Wright Literary Award for Best Adult Fiction this March, so it’s no surprise that most of these authors returned for a sequel collection and even picked up a few other writers along the way.

Unlike the first Malfunction Junction, whose uniting element was simply that the stories were set in Memphis, this second collection explores the theme of encounters — that, yes, happen to happen in Memphis and the Mid-South area. For Malfunction Junction Vol. 2: Close Encounters of the Third Street Kind, returning writers Rikki Boyce, April Jones, Rae Harding, Justin Siebert, and Daniel Reece, plus newcomers K.M. Brecht, Cori Romani, Michael Chewning, K.D. Barnes, and Imogean Webb, have each approached the theme in unexpected ways, varying in genre from horror to fantasy to mystery.

Within the pages, you’ll read of a vampire during the yellow fever epidemic, a satyr romping down Beale, a demon at the Crystal Shrine Grotto, an experimental project with the MPD, and a drink with a familiar stranger at RP Tracks. Compelling and unmistakably Memphis, these stories will leave a reader hoping for a third Malfunction Junction.

— AM

The Dawn of Everything, David Graeber and David Wengrow

I’ve been addicted to Sid Meier’s Civilization games for longer than I’d like to admit. Players start in the middle of a map of unknown territory with a settler to found a city and scout to look around. The challenge is to explore new lands, discover new scientific principles, exploit natural resources, increase in wealth, found new cities, and go to war to expand your civilization until it dominates the world. The mini-narratives of alternative history which emerge from the game can have uncanny parallels with real history — when the bloody remnants of your grand army are retreating from your rival’s capital, you understand how Napoleon screwed up so badly. In my perfect world, one of the presidential debates would be replaced with a Civilization V tournament.

But the world we live in isn’t perfect and never has been. What if we’ve been going about this “civilization” thing all wrong?

That’s the premise of The Dawn of Everything by anthropologist David Graeber and archeologist David Wengrow. The book begins by questioning the concept of the “noble savage,” first popularized during the Enlightenment by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, which posited that humanity used to live in a naive state of equality and squalor until the development of agriculture led to the founding of cities. The evolution of hierarchies like king and peasant emerged from necessity. Graeber and Wengrow use recent discoveries to weave together the argument that complex social structures and hierarchies long predated agriculture. The people who built Göbekli Tepe, the 9,600-year-old temple in Turkey that is the oldest known permanent human structure, were hunter-gatherers, not pastoral farmers. Nor is progress a given: There’s evidence that prehistoric inhabitants of England developed agriculture, then abandoned it in favor of a diet based on hazelnuts, before learning to farm again.

At 704 pages, this is not a quick beach read. Graeber and Wengrow are good enough writers to sustain your interest through chapters with titles like “In Which We Offer A Digression on ‘The Shape of Time’” and “Specifically How Metaphors of Growth and Decay Introduce Unnoticed Political Biases Into Our View of History.” They wield a dazzling array of historical anecdotes which challenge conventional wisdom about who we are and where we came from. You’ll sometimes find yourself questioning their conclusions, but that’s the point of the book. Human societies have come in all kinds of flavors, and there’s nothing inevitable about how we live now.

— Chris McCoy