We are sure to be awash with remembrances of President John F. Kennedy as we mark the 50th anniversary of his assassination this month. There will be much hagiography, some of it deserved, some of it utterly blindered. But what is true is that back then, with Kennedy’s “New Frontier” rhetoric about “unfilled hopes, unconquered problems of ignorance and prejudice, and unanswered questions of poverty and surplus,” there was a sense of moving forward, especially to address the persistent problems of poverty and inequality.

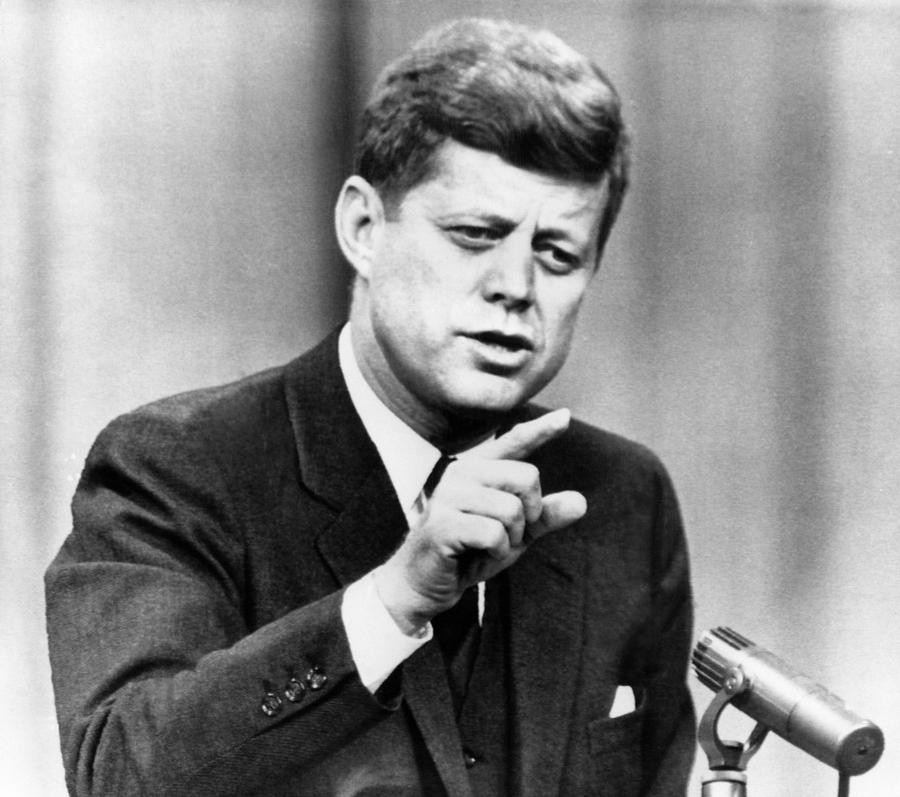

John F. Kennedy

So as we look back, why not take this moment to compare where we were then to where we are now? How much better and how much worse off are most of us, 50 years later?

Back then, on average, women were making 59 cents to a man’s dollar, consigned to a narrow range of jobs — schoolteacher, waitress, nurse — and virtually barred from a host of others — doctor, electrician, Newsweek reporter, you name it. The median income for African-American and other racial minority families was 53 percent that of white families. And in parts of the country, blacks were subjected to poll taxes, literacy tests, and other restrictions on their right to vote. Connecticut prohibited the use of contraceptives. Gay people had to remain closeted in the face of deep and widespread bigotry.

We can, of course, see progress today: In 2013, we have our first mixed-race president; women make roughly 77 cents to a white man’s dollar (though the gap is larger for African-American and Latina women); and gay people can legally marry in 13 states. But there has been a sea change for the worse in the “common sense” of the nation, thanks to a long-term war of position by conservatives.

Established during the New Deal and cemented during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations was the notion that the government had a responsibility to protect people from the vagaries of capitalism and, with the rise of the civil rights movement, to try to promote and ensure equal rights for all citizens. Let’s remember, for instance, that in the summer of 1963, Kennedy signed the Equal Pay Act into law, which abolished wage discrimination based on gender. Today, even after the financial crisis, Republicans continue to insist on an ideological and unrealistic market fundamentalism that strips the government of any responsibility for people’s well-being or security. New polling data shows that among Republicans and independents, support for government solutions to public policy problems actually decreased after 2008.

This leads us to another sharp contrast between then and now: Back in 1963, the John Birch Society (a far-right radical group) was so marginalized that conservative patriarch William F. Buckley Jr. denounced its members as “far removed from common sense.” Now, right-wingers just as far removed from common sense — the climate-change deniers, contraception revokers, and Affordable Care Act scorchers — actually control large parts of Congress, a state of affairs unimaginable 50 years ago.

And here are the real costs of that shift: Economic inequality in the U.S. has soared. The middle class continues to disintegrate as the faltering economic recovery benefits the upper 1 percent; CEOs make 201 times the wages of regular workers, compared to 20 times as much in the 1960s. In 1963, the highest marginal tax rate on the rich (those making more than $400,000 a year) was 91 percent; today, even the super-rich pay no more than 39.6 percent, and they’re still moaning, despite the fact that by taking advantage of tax breaks and offshore assets, few of the super-rich actually pay anywhere near that percentage. And the wealth gaps between whites and minorities are at their widest in a quarter century.

In 1963, the prevailing discourse of progress and modernity, of equality for increasing numbers of Americans, was gaining serious moral purchase, however virulently the Birchers and others fought it. Today, the radical right assaults this discourse and seeks to have everyday Americans buy into its reactionary agenda. It’s not that they’re winning, but they are obstructing the country in profound ways. Where’s our sense of progress, of being at the vanguard of history, now? It’s been thwarted; smothered.

So as we look back at those black-and-white images of Camelot and the Kennedy years, we can think how far we’ve come. But we also have no choice but to see how far we have fallen back and to see that we have a long battle ahead to reclaim what counts as common sense in America.

Susan J. Douglas is a feminist academic, columnist, and cultural critic who writes about gender issues, media criticism, and American politics.