As the rain clouds that doused West Tennessee on Monday passed eastward on Tuesday — in the direction of Republican Bob Corker’s presumed stronghold of East Tennessee — Democrat Harold Ford Jr. had every reason to hope for a perfect storm that would elevate him to the U.S. Senate.

It would end imperfectly for the Memphis congressman, however, three percentage points and some 40,000 votes behind his more mundane opponent. At The Peabody, where there was a goodly-sized media contingent and a giddy crowd had gathered for a potential celebration, hope dimmed only gradually.

And when, well after midnight, a somber Ford finally reached the podium and looked out over his sea of faithful supporters, some of them still calling out encouragement as if the next day would bring another vote, another shot at glory, the look of blank disappointment on his face said something otherwise.

It attested to the congressman’s realization that his own — and his family’s saga — had reached a turning point. Not only had he lost, but so had brother Jake, a poor second-place finisher (as an “independent”) to Representative Ford’s soon-to-be successor in the 9th Congressional District, Democratic nominee Steve Cohen — who even then was reveling with an exuberant crowd of his own supporters at Palm Court in Midtown.

As Ford spoke his brief subdued remarks of concession to a gathering that included Uncle John Ford, who resigned from the state Senate last year and faces imminent trial for his role in the Tennessee Waltz scandal, it began to dawn on some that the proud political family’s ranking official had suddenly become Ophelia Ford, the modest and muted successor to powerhouse brother John as senator from District 29.

Presumably, her margin of victory over Republican Terry Roland had been substantial enough this time to withstand the charges of vote irregularities that earlier this year caused her Senate colleagues to void her narrow victory in a 2005 special election for the seat.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

John McCain (center) stumps for Bob Corker in Nashville

Though the national media saw in Tuesday’s outcome only the abrupt (if perhaps temporary) end of the golden-boy saga they had been chasing these last several weeks and months, the local subtext of the election results had to be: What next for Harold Ford Jr.? What next, indeed, for the Fords?

There had been signs, to be sure, that the weather was turning irreversibly against Representative Ford.

As the campaign wound down and the last week’s polls showed GOP adversary Corker with a double-digit lead, it began to seem that the congressman had over-reached himself — that his family history would trip him up, if nothing else.

Some Democrats — local and statewide — took umbrage on election day upon hearing that Harold Ford Sr. — the Florida lobbyist, former congressman, and Ford-clan patriarch — was putting out copies of a “Harold Ford Sr. Approved Democratic Ballot” on which his second-born son, Jake Ford, had the place of honor for the 9th district rather than Cohen, the Democratic nominee.

That smacked too much of the old Ford machine for various Democrats, whose loyalty to Harold Ford Jr.’s curiously new-breed politics — ranging from indistinct to undeniably right-of-center — was tenuous at best. (See “The Third Man”)

Discontent with Ford among hard-core Democrats may have been a marginal affair, but further analysis may show that this election actually hinged on the margins.

Any student of the blogosphere — suddenly swirling with political dervishes in Tennessee as elsewhere — could attest to the passions that were driving partisans at the edges of ideology. And, whereas in the outer, traditional world, ads for the pious, button-downed-collar Ford were making converts — such as Knoxville’s Frank Cagle, a journalist and conservative activist of the old school — he was still being regarded with suspicion online by red-hots both left and right.

Beyond the convenient descriptors of race or party label, there was in fact not much in the way of ideological difference to distinguish between Corker and Ford. Whatever their private convictions, both had progressively moved from their party’s moderate wings to positions that were clearly right of center.

Both candidates, formerly pro-choice on abortion, now described themselves as pro-life. Both opposed gay marriage. Both favored an extension of the Bush tax cuts, opposed immediate troop withdrawals from Iraq, and supported the president on the so-called “torture” bill. Their differences even on issues like tort reform and Social Security were being fudged.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

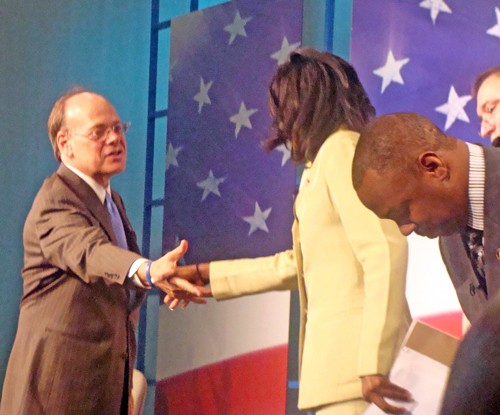

Steve Cohen at his Palm Court victory party

So it came down to a contest between individuals — Corker, the plain-spoken businessman and former Chattanooga mayor, versus Ford, the dazzling, charismatic wunderkind of 2006.

Right up to the end, Ford was routinely being described by those pundits who were hazarding election forecasts as having run this year’s best campaign. But that surely was a paradox: In the year of a roaring Democratic tide, with personal gifts that were undeniable and with coverage of his race with Corker devoted disproportionately to him, how indeed could Ford have lost?

One clue, perhaps, was the debate that raged amongst progressive bloggers in Memphis. It narrowed down to the following choices: Hold your nose and vote for Ford, whose politics had gone conspicuously rightward; vote for a fringe candidate of the left, such as the Green Party’s Chris Lugo; desist from voting in the Senate race altogether; or, as a fourth alternative that came to be increasingly taken seriously, vote for Corker.

Several developments drove that resolution: There was a factor that loomed much larger in Tennessee than elsewhere, where pundits chose to ignore that old chestnut about all politics being local. This was the fact, familiar to most Tennesseans within reach of a TV set or a morning newspaper, of the Ford family of Memphis, a.k.a. the Ford political “machine.”

The franchise began in 1974, the year of Watergate, when a two-term Democratic state representative named Harold Ford won an upset victory over white Republican Dan Kuykendall. Soon, Ford Sr. (the suffix, of course, derives from latter-day circumstance) was encouraging his siblings — all, like him, the sons and daughters of N.J. and Vera Ford, operators of a successful South Memphis funeral home — into the new world of politics.

Such were the leadership skills of the first Congressman Harold Ford that soon there were Fords everywhere in government — on the City Council, on the County Commission, in both chambers of the Tennessee legislature. Over the years, those family members, like John Ford of the state Senate, became dominant figures — exercising power up to, and sometimes beyond, established governmental lines.

John Ford’s indictment last year and subsequent resignation capped a swaggering, often scandalous career in which the senator’s very real legislative acumen soon became a secondary issue in the minds of Tennesseans. Ironically, the senator’s arrest in May 2005 occurred on the very eve of his nephew’s announcement for Senate.

Harold Ford Jr., raised in Washington, D.C., and schooled in such environs as St. Alban’s Prep School, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Michigan, had every chance to avoid being stereotyped as “one of the Fords.” First of all, he was different — even early on, he was the same smooth article that TV viewers saw this year in Ford’s political ads.

Almost preternaturally self-assured and glib, he moved into the frames of his commercials and hit his marks with a grace and flourish that any professional actor might admire. Indeed, he was so accessible a figure that reigning political shibboleths ceased to be of any use to would-be analysts. It had long been said, for example, that no black could win in Tennessee.

Ford’s U.S. Senate candidacy directly confronted that assumption. It soon became clear that, while he was black enough, at least in concept, to be the overwhelming favorite son of the state’s African-American constituencies — 16 percent of the total population — he also conformed closely enough to middle-class models of success that crowds of young white professionals soon began to crowd his rallies. His professions of piety (he called himself “Jesus-loving” and began to carry a Bible on the stump) proved effective in rural surroundings and even on TV, where his nods and finger-pointing heavenward was reminiscent of famous pro athletes.

One measure of Ford’s possible appeal to social conservatives was that in Shelby County — where, as returns approached completion, he was maintaining a consistent 65 percent of the total vote — the referendum on state Amendment One, which would ban gay marriage, was winning by tidal-wave proportions — 80 percent to 20 percent. At the very least, this meant no sign of the usual anti-Democratic backlash that in recent years has accompanied evangelical voting.

In retrospect, Ford’s strong showing should have surprised no one. Added to his personal panache — virtually without parallel among Tennessee politicians, black or white — were the facts of an undeniable voter discontent with Republican rule and, for that matter, with politics-as-usual.

But the three percent lead that Bob Corker held onto as a margin never disappeared. And as news organizations began to call the race for the Republican, Harold Ford Jr.’s excellent adventure finally expired.

In the end, the same factors that gave him his chance ultimately may have doomed him to defeat: He lacked an important part of his base. Close, but no cigar.

After all the excitement, after all the better-than-expected election results in Shelby, Davidson, and Hamilton counties (all urban centers), Harold Ford did what most Tennesseans thought he would do at the beginning of his race: lose to an established Republican in a taken-for-granted red state.

Maybe it was never possible he would win. At the end of it all, campaign strategist Tom Lee acknowledged to the media that his candidate had reached or achieved most of the campaign’s goals, falling short, perhaps, only in the upper northeast corner of the state, the so-called Tri-Cities of Kingsport, Bristol, and Johnson City, traditional Republican strongholds all.

Maybe it was what the national media saw as racial content in the infamous line, “Harold, call me,” spoken by a white bimbo in a Republican National Committee ad — though most Tennesseans doubted it. Indeed, Ford seemed to do well among young, white professionals, who flocked to his rallies and sported his bumper stickers on their Volvos and SUVs. Indeed, they were as much a core constituency as African Americans were.

And he seemed to do well in some of the rural counties where a state constitutional amendment to ban gay marriage also ran up a big vote. At various times, he even appeared capable of doing the impossible — stealing the religious vote from the Republicans. He promised on national TV that he would be a “Jesus-loving, gun-supporting” senator; he began toting a Bible on the stump and seemed about to create a brand-new political type.

But red-state reality insisted on asserting itself.

Even in his concession speech before adoring supporters at The Peabody, Ford clung to that most surprising and unexpected component of his 2006 persona. Quoting passages of scripture, he made one last nudge of head upward, pointed heavenward one last time, and thanked his maker, the celestial one, for the opportunity to do what he had almost done. And then, after having spoken the merest congratulations to his victorious opponent, he moved offstage, slowly, as most disappointed mortals would, the consoling arm of congressional colleague Lincoln Davis, his campaign chairman, draped over his shoulder.

Ultimately, Harold Ford Jr. fell back to earth, having fallen just short of becoming a political archetype. But, like Icarus of legend, he made a good flight of it while it lasted.

Meanwhile, Cohen was flying high, having won the 9th District seat with a solid 60 percent margin that exceeded what most of his backers regarded as possible. At 57, Cohen would not only have the opportunity for national office that he had hankered for since his earlier try for Congress in 1996 — against Harold Ford Jr. — he would be privileged to begin his term of service as a member of the House majority. That was a privilege his predecessor had never enjoyed. Even the new congressman’s unabashedly liberal bias — unlike Ford’s conservatism — seemed perfectly in tune with the new Congress, where Democrats had also strengthened themselves in the Senate.

As vintage rocker Randy Haspel played piper for the packed and racially diversified crowd of young and not-so-young Democrats at Palm Court, the state senator’s recent bête noire, the moody, unpredictable Jake Ford, was nowhere to be found.

Absent from his brother’s event at The Peabody, the erstwhile congressional aspirant was rumored to have been involved in this or that fracas on election night. Soon enough, even the gossip about him died down — nobody seemed to care any longer what the facts were — and his somewhat less than 15 minutes in the limelight had pretty much wound down.

It was otherwise with Republican Mark White, the third-place finisher in the 9th, who would presumably be able to translate his newly enhanced name recognition into another — and better — chance at elective office somewhere down the road.

Other results: Something of that sort might also be the case for Democrat Bill Morrison, the Bartlett schoolteacher who waged a spunky if underfunded race against incumbent Republican Marsha Blackburn, an easy winner in the 7th Congressional District.

In the 8th Congressional District, the loser was Republican John Farmer, who had a good time venting his idiosyncratic brand of conservative populism even while losing badly to Democratic incumbent John Tanner. Farmer also lost a race to Beverly Marrero, the Democratic state representative from District 89.

There were no surprises in the other local legislative races. Republican Paul Stanley beat Democrat Ivon Faulkner for Curtis Person’s old District 31 state Senate seat; Democratic incumbent Barbara Cooper won over her perennial GOP challenger, George Edwards, in House District 86; Democrat Mike Kernell continued his personal streak of invincibility against Republican challenger Tim Cook in House District 93; and Republican Ron Lollar beat Democrat Eric P. Jones in House District 99.

Winners in Memphis school board races were: Kenneth Whalum Jr. succeeding the retiring Sara Lewis by a landslide in At Large, Position 2.; Betty Mallott, displacing incumbent Deni Hirsch in District 2; Martavius D. Jones, unopposed in District 4; and Carl Johnson, reelected in District 6.

As indicated, state Amendment One, to ban gay marriage in Tennessee, won lopsidedly, by a 4-to-1 margin, as did Amendment Two, providing property-tax relief for seniors.

Oh, and to no one’s surprise, Governor Phil Bredesen, running against underfunded Republican Jim Bryson, who declared late as the GOP’s sacrificial lamb, won easily in what may have been the most unnoticed major statewide contest in recent Tennessee history — confirmation, if any were needed, that not every contest this year had to be a matter of heavy weather.

jb

jb  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Chris Davis

Chris Davis