In this installment of Never Seen It, I sat down with the boss, Memphis Flyer Editor Bruce VanWyngarden, to check out Stanley Kubrick’s infamous, 1971 low-budget masterpiece A Clockwork Orange. We were joined by my wife Laura Jean, and a couple of bottles of red wine.

BEFORE THE MOVIE

Chris McCoy: What do you know about A Clockwork Orange?

Bruce VanWyngarden: I’m sure back in the day I read a lot about it. I know it’s Kubrick, I know about the Droogs, and I know there’s a lot of violence, and it’s set in some kind of futuristic Great Britain.

CM: Why didn’t you ever get around to seeing it?

BVW: I was probably stoned. When it came out, I was probably 17 or 18. When did it come out?

CM: 1971. After 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick was going to do Napoleon. It was going to be huge—there was going to be 40,000 extras, he was literally going to recreate Waterloo. It never happened. I have a .pdf of the script on my hard drive, but I’ve never actually read it. The whole thing fell apart, and he said, “Screw it, I’m going to make a movie with one light kit.” And that’s what this is.

BVW: My wife’s mother made her watch this over and over again. She was really into it. They were living in France out in the country, and it was one of the few VHS tapes she had. I asked her if she wanted to come see this, and she said no, she had seen it too many times already. She was like, I can’t believe you never saw this! I said, That’s the whole point of the column…At the time, there was suddenly a lot more nudity in movies. I was watching stuff like Blow Up, and my mind was being blown. How did I miss this one? I don’t know.

Never Seen It: Watching A Clockwork Orange with Memphis Flyer Editor Bruce VanWyngarden

DURING THE MOVIE

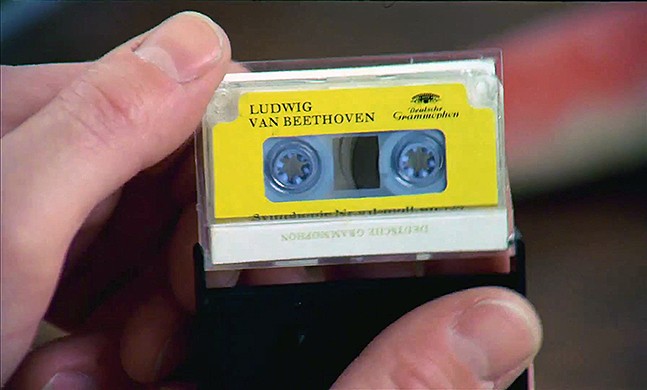

[Alex returns to his bedroom after a long night of rape and pillage to listen to Beethoven]

BVW: The micro cassette was advanced technology in 1970!

[Alex’s mother is revealed to have purple hair]

CM: People in the future really do have purple hair!

BVW: That woman has Eileen Townsend hair.

[Alex picks up two girls at the record store]

BVW: Everyone is sucking on popsicle dicks!

CM: There are a lot of dicks in this movie.

[The infamous time lapse menage a trois]

CM: This has got to be one of the greatest single takes in movie history.

BVW: I wonder how long that really took?

(I looked it up: 23 minutes)

[Alex is sentenced for his crimes]

BVW: 14 years for murder. He got off easy.

CM: You just wait.

[While reading the bible in the prison library, Alex imagines himself as one of the Roman guards taking Christ to the cross.]

BVW: I love Alex’s interpretation of the bible!

[Bruce looks up Malcom McDowell’s IMDB page]

BVW: Oh my god! Do you know how many movies he’s been in? He’s acted in 258 movies! That’s an average of 7 movies a year! That guy works.

CM: He works. And that was because of A Clockwork Orange. Every single director wants him to do Alex.

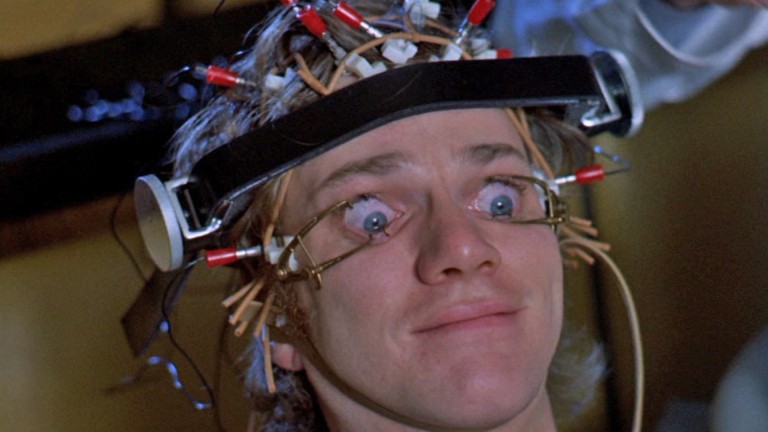

BVW: He should have gotten the Oscar for that eyeball thing alone.

CM: They scratched his corneas and he went temporarily blind.

BVW: You couldn’t get away with that today. That would be CGI. I hope he got paid a lot of money for this role.

AFTER THE MOVIE

BVW: It started out just as intense and crazy and violent as I had expected, except for the cartoonish character of the violence. I watch violent movies now, and I just turn away. I can’t stand it. But like in the early scenes where they’re fighting and beating up the old man, there’s nothing I can’t look at. It wasn’t as horrible as I thought it was going to be.

Never Seen It: Watching A Clockwork Orange with Memphis Flyer Editor Bruce VanWyngarden (2)

Laura Jean Hocking: When the woman gets killed with the big penis sculpture, I can’t watch that.

BVW: I couldn’t watch that, either.

CM: He went totally abstract during that killing.

BVW: There was no visual of it.

CM: t’s like a comedy and a horror at the same time.

BVW: That’s what I expected: Horrible violence and drugs and futuristic shit. But the rest of it, by the third act, I was ready for it to end. I was not as compelled by it by the time it ended as I was in the beginning. It’s totally front loaded…Halfway through the third act, I had to pee. I was like, I’m done with this. But you said it was almost over, and my bladder made it. I was thinking, where is all this going to go? Alex is obviously going to be an evil fuck again. I get it.

LJH: I loved the paparazzi swooping in.

CM: The press is the ultimate bad guy in this movie.

LJH: They validate everyone’s bad behavior.

CM: The motivation of the journalist whose wife was raped and killed in the first act was to ultimately distort society. It’s arguably the greater evil than this thug at the center of the whole thing. As a journalist, that’s weird.

BVW: Oh yeah. I think, after seeing it, Malcolm McDowell should have gotten an award for the greatest physical abuse ever taken by an actor. It was amazing the shit he went through.

LJH: The eyelid thing! Aaaahhh!

BVW: The eyelid thing, and the drowning! He was underwater for a long time!

CM: There are all these huge, long takes, but it ultimately drags. The individual scenes work, but it really doesn’t hold together in the end.

BVW: Maybe it was the wine, but I was dragging at the end. There were not enough tits, not enough beatings, just a whole lot of close ups of people’s faces, leering.

CM: Something I noticed this time was, Kubrick was really excited about his lens choice….When we went to L.A. In 2013, there was a Kubrick exhibit at LACMA…

LJH: There was an entire room that was just his lenses. It was like pornography.

[Extended, largely incoherent discussion of Carl Zeiss lenses, Watergate, Trump, and mid-century modern architecture ensues.]

CM: So, here’s what the ultimate point of the movie, or the text, is supposed to be. Anthony Burgess, the writer, his wife was raped and beaten by a bunch of drunk American soldiers during World War II.

BVW: Americans?

CM: Yes. The novel came from that experience. The central question is, what if you had a technology that could change a person from a criminal to an ideal citizen? Whoever gets to decide what an ideal citizen is. Is Alex actually able to exercise free will and do good, and do his good works have any meaning, as Christian morality would suggest? Or is he just faking it? Is he a robot? It he like an orange, an actual orange that you could eat, or is he a clockwork orange, a fake orange that you can’t eat and therefore has no value? So that’s supposedly the deeper meaning of all this violence and stuff. The one scene when he’s in the theater and he’s the entertainment and they’re all debating about the Luduvoco technique, the priest stands up and says, “If he can’t make a choice between good or evil, this doesn’t matter. Why are we doing this?” That’s the most crucial scene in the movie. Did you get any of that from the movie?

BVW: No. Hell no.

Never Seen It: Watching A Clockwork Orange with Memphis Flyer Editor Bruce VanWyngarden (3)