Mark down 2018 as the year that Memphis music conquered the world — again.

We can dwell on the chart conquests of yore by Sun and Stax, all fueled by the fiercely independent spirit of those studios’ producers and artists. Or we can fast forward to the widespread use of Memphis soul samples by NWA, Snoop Dogg, and others in the late 1980s. Or skip ahead to DJ Paul, Juicy J, Crunchy Black, and Frayser Boy winning an Academy Award for Best Original Song. Even that was a dozen years ago, and was only the tip of the iceberg. As it turns out, that iceberg has been chugging along for decades now, gathering momentum. Now, once again, it has crushed the charts.

“It’s been a big year for Memphis hip-hop,” says Devin Steele, DJ for K97 FM. “Just with Yo Gotti, BlocBoy JB, Moneybagg Yo, and Young Dolph, alone. About a month ago, all four of those artists had records in the top 20. You hear Memphis records on the radio in every major city now.” And that’s not even including less visible Memphians like Teddy Walton, who produced a track on Kendrick Lamar’s Grammy- and Pulitzer Prize-winning DAMN.

Beyond new material, classic sounds from the 1990s and early aughts are being revived as well. Steel explains, “There’s a resurgence of Three 6 Mafia, with people reusing their beats for a lot of popular songs. Like that classic Juicy J song, ‘Slob on My Knob.’ G-Eazy took that record, put Cardi B on it and just redid the record. It’s the same record!”

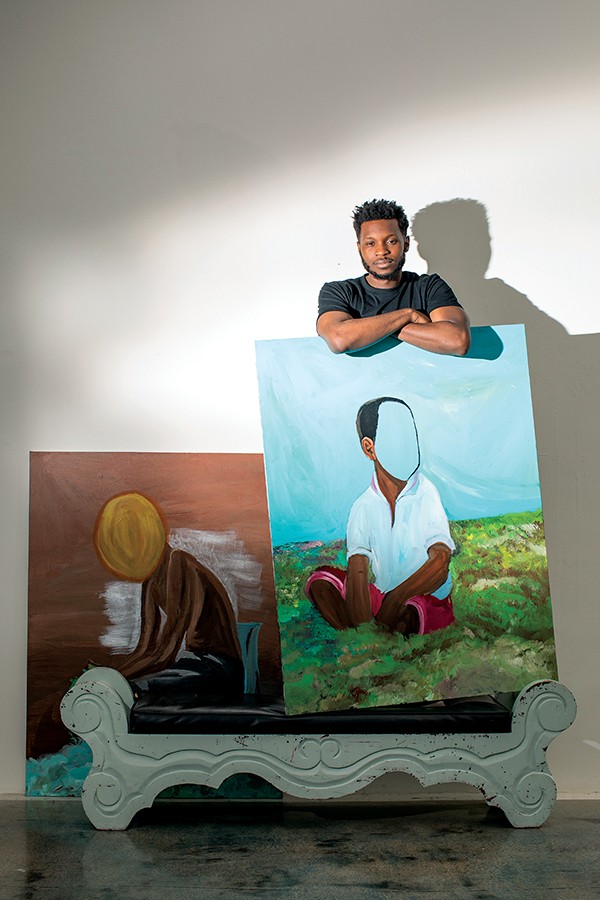

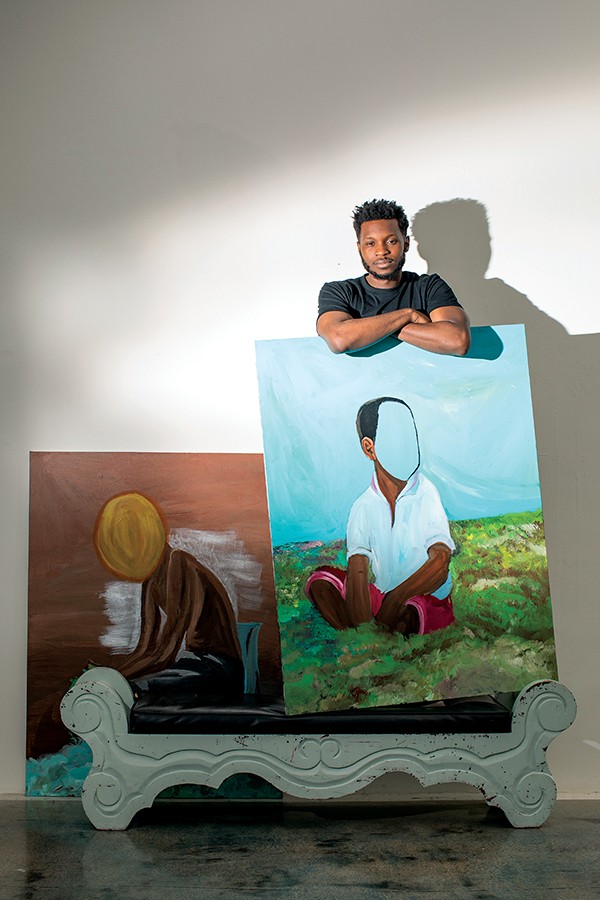

Lawrence Matthews, aka Don Lifted

Indeed, a recent article in Rolling Stone calls Juicy J’s track “the most influential rap song of 2018,” naming no less than three artists who have used it. It’s a rare accomplishment for a song cut a quarter-century ago.

One thing made clear by this is the way a track can live on, independent of any one artist. Aside from Memphis performers who have topped the charts, the success and longevity of those tracks rely heavily on Memphis producers — the unsung heroes of this story.

Many of the new hits, such as “Look Alive,” the BlocBoy JB collaboration with Drake that reached number five on the Billboard Hot 100, grew out of tight connections between artists and producers dating back to childhood. Tay Keith, the 21-year-old who produced “Look Alive,” grew up with BlocBoy JB in Raleigh, and they helped refine each others’ skills in their early teens.

As Keith told Fader magazine, “We used to have everybody in the neighborhood record their music in the garage … [BlocBoy] used to be freestyling to the beat the whole time while I’m making it.” As Keith developed his reputation, he went on to work with Blac Youngsta and Moneybagg Yo. But when Drake connected with BlocBoy JB, it brought a sea change. “It definitely changed my life and opened a lot of doors for me,” he says. “It helped me elevate to the next level. But I’m actually still in college, so I’m basically just working this summer.”

DJSqueeky

Lawrence Matthews, aka Don Lifted, recalls a similar friendship. “Cody Jordan — ThankGod4Cody — he’s a friend. We grew up producing together in a friend’s attic. He ended up moving to Atlanta, then moving to L.A., and now he has two platinum records. He’ll also be featured on my upcoming album. I remember when we used to have parties in my living room in 2011. We were talking about that last week at his place, outside his new studio that they’re building. Sitting in the back yard with a pool and a basketball court, and it’s just like, ‘We’re out here! How did seven years lead us to this?'”

The tale of youthful collaborations leading to great things is common in Memphis hip-hop. As the now-legendary producer DJ Squeeky told the Memphis Flyer of his early days in the late 1980s, “I was probably about 15 [or] 16 years old. I did some work with 8 Ball & MJG, Criminal Manne, Project Playaz, and Tom Skeemask. We all kinda grew up together in the same neighborhood.” Some 30 years later, DJ Squeeky is still making hit records, now with Young Dolph, born about the time Squeeky got started. Their track, “100 Shots,” was just certified gold — Squeeky’s second gold record to date.

Pondering the fact that he, unlike many Memphis-bred artists and producers, still lives in his hometown, Squeeky reflects on the lack of recognition Memphis gets, given its high ratio of talent. “People are just milking Memphis. They’re getting millions of dollars. Everybody’s got the sound of Memphis,” he says. “But Memphis ain’t getting the acknowledgment as the source where they’re getting all this music from, where they’re making all this money. They keep pointing at Atlanta. And it’s really not Atlanta. In Atlanta, they have more belief in rap than we ever had in Memphis. Because they look at it like it’s a business venture. They look at it like, if we spend money, we make money. In Memphis, we get kinda skeptical about spending our money. We gotta think about it three or four minutes.”

It’s a familiar story, going back to a producer Squeeky cites as an early inspiration: DJ Spanish Fly. Now, with his early mixtapes being rediscovered on the internet, Spanish Fly is recognized as a pioneer of the crunk sound. But for years, aside from a few shout-outs by the Three 6 Mafia crew, he went unappreciated. As Squeeky notes, “We’ve been having this sound for the longest time, but nobody called out what we was doing, ’cause we was before our time. But over time, that’s how everybody sounds now. It’s like the sound of the world now is Memphis.”

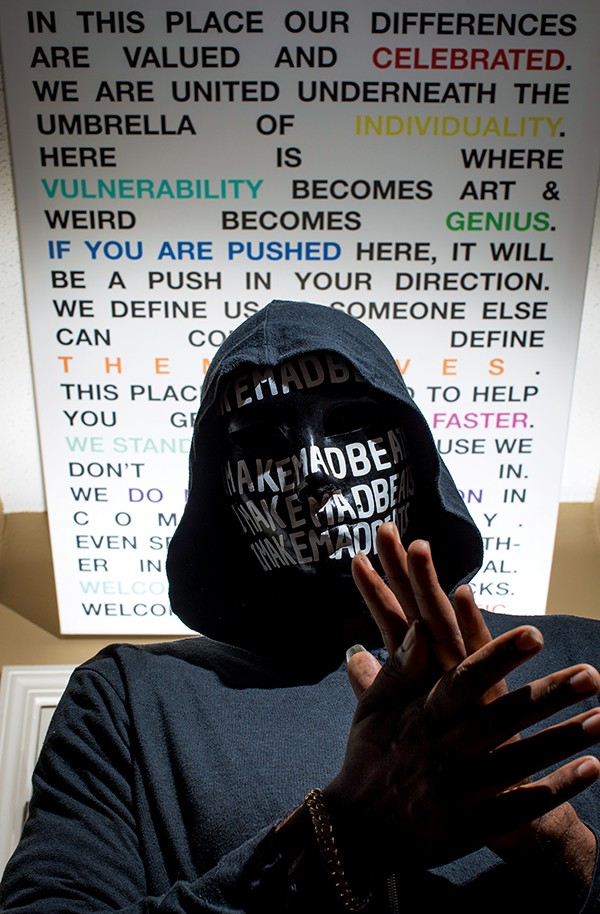

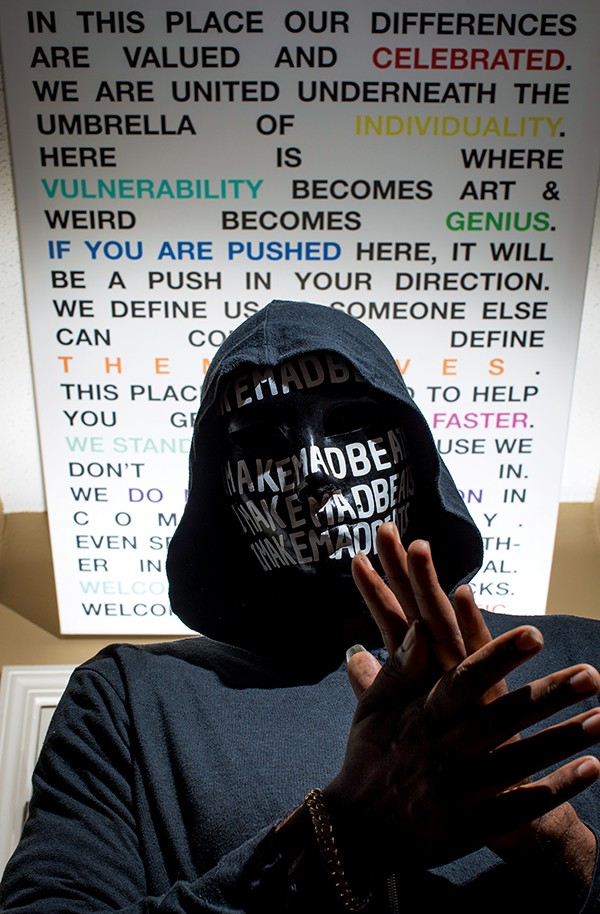

IMAKEMADBEATS

DJ Squeeky, since before his earliest hits with 8 Ball and MJG, has also been an architect of that sound. As Steele says, “His name is coming up a lot with the whole trap vs. crunk debate, over who came up with what, where it came from. Atlanta’s taking credit. Memphis came up with it.”

But what is the Memphis sound? Ever evolving, it’s not easy to define nowadays.

“In Memphis, we have our own sound: the bounce,” Tay Keith explains. “That bounce sets us aside from everybody else.” The prominence of the Roland TR-808 drum machine is a part of that. It figured heavily in hip-hop’s earliest days, but as rap explored sampling more through the 1980s, loops of classic funk and soul drum breaks came to dominate. That is, until Memphis producers stepped up, bringing the 808 into the foreground once again. Over such beats, DJ Squeeky, Three 6 Mafia, and others layered more orchestral sounds, creating the doom-laden “horror movie” sound of the 1990s.

That’s still a defining sound, as the current recycling of old Three 6 Mafia tracks proves. But records from the new generation of Memphis producers, like Keith, can be spare, almost bleak, with the 808 percussion foregrounded even more. This is calculated.

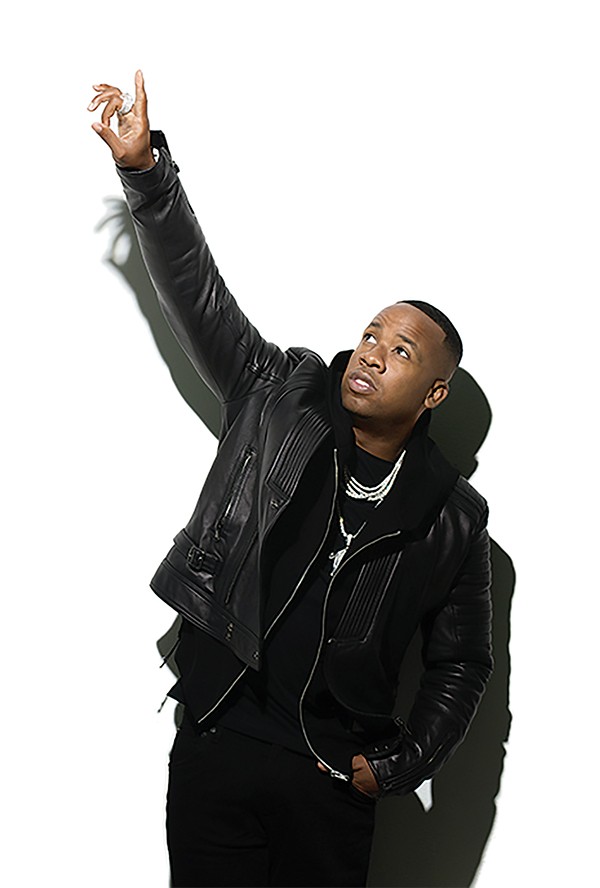

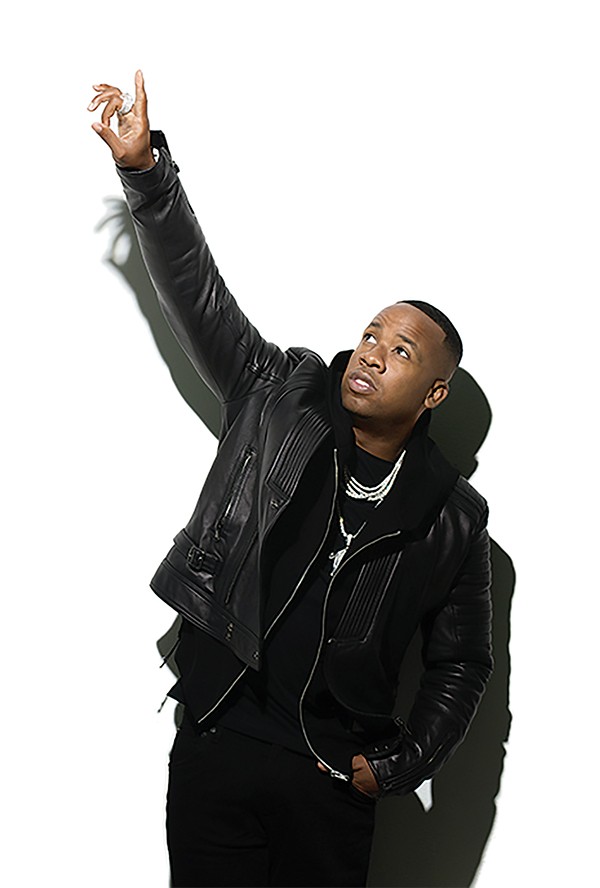

Yo Gotti

As Keith explains, “You make the beats simple so you give the artist more room to ride the beat. If you put too much into a beat, artists really don’t have much room to do what they want. The simplicity is the creativity.”

DJ Squeeky puts it another way: “The new people making the new trap sounds, they’re making the beat with less of the music. When I was coming up, we had more music. It was in our blood with the Memphis sound, to have more music in a track — guitar, pianos, and all that other stuff. I grew up on a lot of that. So I added a lot of that to my tracks.” Having spent his early years as a drummer at the First Baptist Beale Church, where his family attended services, he’s still committed to layering more sounds over his beats.

But DJ Squeeky isn’t the only producer from Memphis with a musical background. Alan Hayes is possibly the least recognized Memphis hip-hop producer/engineer, emerging as he did out of the white rock and new wave scenes of the 1970s and 1980s. He, too, notes the change in the recent hip-hop soundscapes. “It seems to me that the tracks have gotten a lot less musical and a lot more beat-oriented. Now it just seems like the music is just some kind of ethereal bed underneath a big giant 808 kick and snare.”

A paradoxical figure in Memphis rap, Hayes is a missing link between the city’s electronic music scene of the 1980s and the hip-hop that was to come. Having played with successful electronic new wavers Calculated X, he already had a TR-808 and many other synthesizers when he built his House of Hayes studio around 1988. Thus, he was perfectly poised to catch the initial wave of Memphis rappers.

Tay Keith

“The first rapper I worked with was named AlleyCat. The producer was Carlos Broady (another Memphis native). This was right after he had done the stuff with Biggie Smalls.” Soon thereafter, Hayes cut the first demos of a 15-year-old named Yo Gotti, whose success led to more work in the genre, such as Gangsta Blac’s 74 Minutes of Bump. But he credits another studio as the scene’s true pioneer. “MegaJam was probably the earliest commercial hip-hop studio in Memphis. One of the guys there was Michael Patterson. He’s now done a lot of big time stuff.” Kojack, another renowned producer from Memphis, also started at MegaJam.

Though Hayes produces and engineers many styles of music, he hasn’t lost the enthusiasm for hip-hop that he felt in those early days. “There just aren’t any rules of what you can put together to make a beat,” he says. “I bought my first synthesizer, a Minimoog, probably about 1971. And I’ve always been just as enamored by sound and texture as actual music, you know? So hip-hop was a huge opportunity to just go wild with weird sounds and stuff.”

[content-7]

The idea of “going wild” is significant. Though the current trend is minimalist, the more expansive possibilities of hip-hop are still alive and well in Memphis, and not just with musician-producers like Squeeky or Hayes. Under the surface of the Memphis-derived hits, the city is witnessing an explosion of creative approaches.

The Unapologetic label/collective, for example, is premised on the notion of diversity. Memphian James Dukes left town after high school for a job at Quad Recording Studios in New York, working with Talib Kweli, Common, Missy Elliott, Ludacris, and others. Unlike many, he returned here in 2011. “New York toughens you up in a very interesting way, in a very social kind of way,” he says. “I would say I went up there as Nemo, which was just a nickname, and I came back IMAKEMADBEATS, a kind of scarily dedicated guy.”

Kenny Wayne

Dukes found himself pursuing a richer vision of what Memphis hip-hop could be. Inspired by other like-minded Memphians who chafed at the new “Memphis sound,” he founded Unapologetic to nurture their work.

Now, a few years on, Unapologetic has developed a stable of artists and producers who evoke the freewheeling spirit of the Native Tongues collective in late-1980s New York: rappers like PreauXX and A Weirdo From Memphis; producers like C Major and Kid Maestro; less rap-oriented artists like angelic singer Cameron Bethany or bass phenom MonoNeon; and even a clothing line. The musical environments created by IMAKEMADBEATS and his fellow producers are imaginative and eclectic.

One precursor to the Unapologetic model was the Iron Mic Coalition, which held to a similar set of values, though not with the same production and marketing savvy as Dukes and his cohort. Dukes counts them as an inspiration, especially the work of Ennis Newman, aka Fathom 9, who passed away in 2014. Dukes recalls, “While the I.M.C. has various talents, Fathom 9 to me was the most left wing. He was past the point of comfortable and cute. He did it in a way to where it was daringly uncomfortable.”

Which brings us to the “message”: While overt politics mostly emerge in rappers’ lyrical choices, they inform the production as well, and it’s clear that groups like Unapologetic and I.M.C. create a milieu where politically conscious rap can flourish. Of course, you can’t dismiss the raw political impact of Three 6 Mafia or Yo Gotti raps, even if they mainly celebrate the classic outlaw hero. But conscious rap is less conducive to the call-and-response chants of crunk.

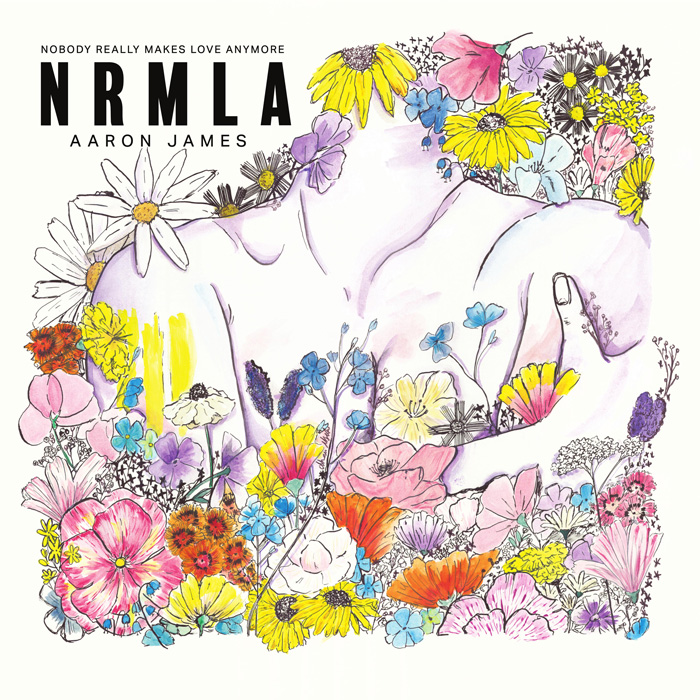

(Clockwise from top) IMAKEMADBEATS, A Weirdo from Memphis, PreauXX, Aaron James, Quinn McGowan, Jr., Kid Maestro, Eric Stafford, C Major

When I ask IMAKEMADBEATS about political rappers in Memphis today, he singles out two. “Marco Pavé is one. He’s built a whole identity around it. And Don Lifted. His stuff is maybe not as aggressive in that sense, but he’s very aware.”

Don Lifted and Marco Pavé are indeed a study in contrast. Don Lifted, a member of the mostly visual arts-based group The Collective, curates his own and others’ artwork in local galleries, creates objets d’art as set pieces for his concerts, and is one of many local rappers who produce their own tracks. C’Beyohn, Cities Aviv, and Kenny Wayne (also a visual artist in The Collective) all work in this way, often combining autobiography with “message” rap.

Pavé presents himself as more of an activist and auteur, though he relies on producers like Broady to create striking juxtapositions of samples and lyrical protest. Wayne also creates tracks for Pavé, and the two have recently been scoring their hip-hop works for live orchestra. This may represent the newest frontier in the genre. Sam Shoup, an arranger and instructor at the University of Memphis, tutored Wayne in conducting classical musicians and assisted with an operatic version of Pavé’s Welcome to Grc Lnd. He finds Pavé’s approach “very interesting. His vision is huge. It could be a landmark piece to come from this town.”

But it was not Shoup’s first run at genre-busting. “This started about four or five years ago, when I arranged the Opus One show for Al Kapone [with the Memphis Symphony Orchestra],” Shoup recalls. “That was one of the first orchestral rap things ever done. And so we kind of pioneered that. Recently Nas did a concert with the National Symphony. Al Kapone was texting me and saying, ‘Man, we did this four years ago!'”

Wayne, whose brother is producer WeboftheMacHinE (a collaborator with Missy Elliot, Timbaland, and Young Dolph), is far from alone in breaking into the realm of live musicians. During Memphis’ MLK50 commemorations, students from the University of Memphis Department of Music staged an original hip hop symphony, “Echoes of a King.” With a jazz band on the left, a string section on the right, and several impressive rappers and singers weaving in vocal parts, the work was a stunning taste of what R&B-tinged hip-hop can become.

While it’s difficult to call such grand explorations “underground,” they certainly exude an indifference to the usual markers of commercial success. But that’s not to say any of these alternative artists would shun more public acclaim. There’s always the chance that, in following their unique visions, they’ll build a larger following. Indeed, they already are.

The bottom line: Memphis is teeming with producers, and even the chart-toppers are pushing their creativity to the limit. As Tay Keith says of his success with BlocBoy JB, “We just did it in more of a creative way than other people. My advice would be to be more creative with it. Stick with a new rhythm, your specific way.”

Clearly, dividing producers or rappers into commercial vs. underground realms is too simplistic. As IMAKEMADBEATS notes, “I don’t think there’s a binary way to look at it in 2018. I think the angle that we want to focus on most is the future progression. For example, what has been deemed an underground sound, like Memphis crunk in the ’90s, became commercial simply because it got the right visibility. So what is underground is very relative.”

This in turn has a direct bearing on a city’s musical identity. Pavé notes that “for Memphis to become the city that it needs to become, music-wise, we definitely have to create other types of sound, other types of rappers with different images.”

Editor’s note: Andria Lisle offers a comprehensive guide to the best spots in Memphis to hear hip hop.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker