It was 1968. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, giving the civil rights era a tragic coda. In June, Bobby Kennedy, the front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination, fell to an assassin’s bullet. The Republican and Democratic conventions were to be held in August, and the three television networks were planning the same gavel-to-gavel coverage they had been doing since 1948.

But ABC had a problem. As the perpetual third-place network, they couldn’t afford to send a horde of reporters scurrying over the convention floor. So they settled on a cheaper alternative: They would invite two intellectuals, one conservative and one liberal, to a no-holds-barred political debate live on the air. The choice to represent the conservative side was easy: William F. Buckley Jr., founding editor of the political magazine National Review. His writings had formed the foundation of what we now call the conservative movement, and two years earlier he had started his own political television program called Firing Line.

Buckley immediately accepted the invitation. Who would you like to debate, ABC asked? Anyone but Gore Vidal, he replied. The unabashedly liberal, sexually ambiguous author of Myra Breckinridge was the antithesis of everything Buckley stood for. He hated that guy.

Naturally, ABC called Gore Vidal.

Fundamental Issues

Memphis director Robert Gordon’s new documentary, Best of Enemies, tells a story that has been lost amid the greater drama of a country tearing itself apart. The televised debates between Vidal and Buckley reverberate across the years, setting the stage for the political and media landscape where we find ourselves as we gird for another political battle for the future of the nation. “It — 1968 — was such a volatile year,” Gordon says. “It was when the frame that held America together came undone.”

Gordon co-directed Best of Enemies with Morgan Neville, whose Twenty Feet from Stardom won Best Documentary at last year’s Academy Awards. The pair have previously collaborated on films about Johnny Cash, Muddy Waters, and Cowboy Jack Clement. Since their work (as well as Gordon’s other books and films, such as the Stax Records history Respect Yourself) has dealt primarily with musical subjects, a political documentary seems like a big departure. But Gordon says it wasn’t a stretch. “Morgan and I both liked using the subject of the film to explore deeper, wider territory. So the documentary on Stax is a lot about the civil rights movement in America. Johnny Cash’s America is about the fundamental issues of democracy in America.”

Prize Fighters

The 1968 Republican convention in Miami was a well-oiled political machine, with Buckley acolytes Ronald Reagan and Nelson Rockefeller lining up behind nominee Richard Nixon. The ABC coverage of the convention was a comedy of errors. The only thing that went right was the 15 minutes every night when the cameras were trained on Buckley and Vidal. The pair circled each other like prize fighters, unleashing flurry after flurry of verbal attacks, with neither seeming to lay a glove on the other. It was riveting television.

“You just don’t ever get to see fully completed thoughts on TV any more,” Best of Enemies editor Eileen Meyer says. “You don’t get to see people like Buckley. His sentences were two or three minutes long. You can barely comprehend what he’s talking about. I had to watch the debates over and over and over again before I fully comprehended everything that was in there, and I still don’t get maybe a third of it. They were just so far above anyone’s intellect, and yet they were entertaining and fun to watch.”

Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

Gore Vidal in Best of Enemies.

A Long Memory

Best of Enemies took five years to make, but its roots go back to the early 1970s when writer and publisher Tom Graves was a Memphis State student interested in politics. “I knew of Vidal as a novelist and Buckley as a conservative spokesman who was on TV,” Graves recalls.

His interest was piqued when he came across their dueling articles in Esquire that were published in the aftermath of the 1968 debates. “I was absolutely amazed by what I had read. These two guys going head to head was better than Muhammad Ali’s ‘Thrilla in Manila.’ This is incredible word-slinging. What a mass of rhetoric! It was verbal fencing,” he says.

Graves wanted to see the debates for himself, but in the pre-VCR era, it proved impossible. “I never lost interest in this, ever,” he says.

He wasn’t the only one. Years later, Graves discovered Vidal had copies of eight of the debates, but in an obsolete video format. Graves arranged with the writer’s camp to have the tapes professionally transferred to DVD. “I thought maybe I could turn this into some kind of Frost/Nixon kind of play. But I’m not a playwright.”

In 2010, he arranged a screening of the debates at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art. He didn’t expect much interest, but “it was not only sold out, they had to turn quite a few people away.”

Among those in the audience was Gordon. He saw the potential in the footage and contacted Graves, who recalls him saying, “My partner’s Morgan Neville, and if I were to do this as a solo project, he would never forgive me.”

Blood in the Streets

Three weeks after the Republican convention, the Democratic Party gathered in Chicago. The death of Kennedy had thrown the Democratic race into chaos, and the convention devolved into a fiasco of historic proportions. The floor fight between Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern was soon overshadowed by the events outside the hall, where Mayor Richard Daley’s heavy-handed police force helped escalate anti-war demonstrations into all-out riots.

On the air, Buckley and Vidal went at it again. Word had spread of the verbal fisticuffs, and the nation tuned in. They were not disappointed. Buckley was smug, confident he could exploit Democratic divisions. Vidal, the radical, was incandescent, railing against Buckley’s brand of conservatism and the Democratic pro-Vietnam war faction, led by President Lyndon Johnson, whose back-room dealings secured the nomination of Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

By the penultimate night of the convention, with blood flowing in the Chicago streets, the gloves had come off in the ABC studios. Vidal baited Buckley relentlessly, and when he equated Buckley’s conservatism with outright fascism, Buckley’s carefully constructed patrician demeanor slipped. He called Vidal a “goddamn queer,” and the debate was on the verge of physical violence when moderator Howard K. Smith stepped in. Backstage, Buckley flew into a rage while Vidal declared victory and partied with Paul Newman.

But the real winner was ABC, which, over the course of August, went from last to first in the ratings.

Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

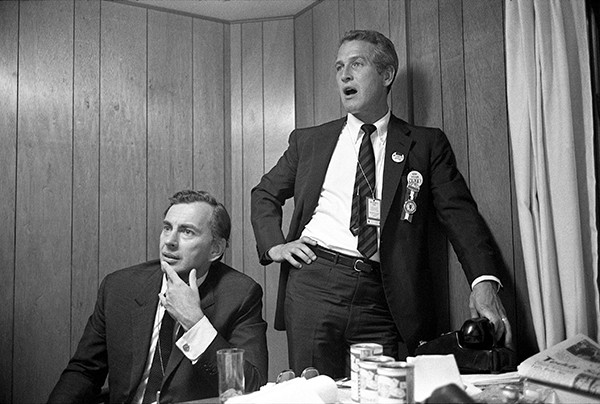

Gore Vidal and Paul Newman in Best of Enemies.

Digging Into the Past

“ABC was supportive from the beginning,” Gordon says. “They didn’t understand immediately, but I won their trust. Then I called Morgan and told him I had this great idea, and could I send him a DVD?”

Unexpectedly, Neville had a connection with the material. “His first job out of college was fact-checker at The Nation, and he was Vidal’s fact-checker,” Gordon says. “It was the worst job he ever had. Gore did not like being told he made mistakes. Morgan saw the same thing I did — that these debates represented the culture wars in America today and that they were articulating both sides so well, yet it was 45 years old. We both saw this as a very contemporary project.”

Gordon, Neville, and Graves set up interviews with political and media figures, including talk-show host Dick Cavett, columnist Frank Rich, and Vanity Fair editor James Wolcott. “They saw what we saw, that they could talk about all kinds of contemporary issues by talking about the enmity between these two guys,” Gordon says. “When we finished the first interview with Wolcott, I knew we had a great movie.”

They managed to secure one of the last interviews with the late writer Christopher Hitchens. “I was so nervous going in there,” Gordon says. “It was two weeks before he was diagnosed with cancer. He wasn’t ill yet. It was a delightful evening of cocktails and talk.”

“We had so much fun. I hope it comes across,” Graves says.

Hollow Victory

In August 1968, the consensus was that Vidal had won the debates. But it was a hollow victory. With the Democratic Party in disarray, Nixon handily defeated Humphrey. “In the immediate days and weeks after the convention, Buckley’s ideas won out,” Gordon says. “They reached their epitome with Reagan, who is still the icon of the Republican Party. Though people no longer know who Buckley is, they know Buckley’s ideas, because they know Reagan. But it’s been interesting to see, in the past half-dozen years or so, the turn to where Vidal’s ideas are having their moment: Gay rights, marijuana legalization, these ideas that seemed so far out back then are finding their way into the American mainstream.”

Although it was not obvious at the time, the Buckley-Vidal debates marked the beginning of the modern age of political punditry. By the time the 1972 conventions rolled around, all three networks had teams of ideologically opposed commentators debating the issues of the day. Gavel-to-gavel convention coverage was a thing of the past.

Greenlit

“It was one of those stories that we had to find it as we went along,” Neville says. “And it was one of these rare experiences on a film where every stone we turned yielded some nugget that just made it richer and richer. Oftentimes, in a documentary, you’re searching for the characters or for dramatic tension. This film had all that in spades.”

Work on Best of Enemies was on and off. The team struggled to secure funding, get interviews, and uncover new archival footage. “Morgan probably made five documentaries in the interim, and he was piggybacking shoots for this onto those.”

Memphian David Leonard shot many of the interviews, and Meyer edited scenes and trailers together, which were used to try to secure funding from investors and grants from Independent Television Service (ITVS).

“When Robert came to me to talk about the project five years ago, I said, ‘Who?,’ and he said ‘Cool!'” Meyer says. “I hadn’t really thought about the fact that people under 40 don’t know who these guys are. In making the film, it was a fun exercise to try and make it accessible to people who were alive during the events and who knew everything about these guys, and then also to introduce a whole new generation to these two amazing characters and this event.”

Finally, after three years, a grant from ITVS greenlit the project. The final budget was approximately $750,000. “It’s a 90-minute film, and 80 minutes of screen time is archival [footage],” Gordon says. “Hundreds of thousands of dollars went into licensing.”

The money opened up new sources of material. “Everything changed when we got into the ABC archive. They had so much we didn’t know they had, like convention coverage. These films hadn’t been seen in decades. Every time we would hit a splice, it would turn to dust,” Gordon says.

For Neville, the biggest discovery was that the debates were a Hail Mary by ABC. “The real character that emerged while we were making the film was ABC. As the film became more and more the story of ABC, everybody got a little nervous about how they would react. But I have to say, at the end of the day, when we finished the film and showed it to their business affairs, they wrote back and said, ‘It’s a film of quality. We’re a news organization. We don’t believe in censorship. You can use anything you want.’ That’s the kind of thing you want to believe a news organization would say, but I guarantee not every news organization would say that.”

Two Things You Should Never Turn Down

After 1968, Buckley and Vidal both went on to greater successes. For the next three decades, Buckley would take on all comers on Firing Line. National Review became the blueprint for the conservative movement that swept America. Vidal found himself in demand, famously quipping that there were two things one should never turn down: sex and appearing on television. His career as a writer flourished with a series of historical novels, such as Lincoln, Burr, and The Golden Age, earning him the sobriquet “America’s biographer.”

As political TV shouters proliferated, the Buckley-Vidal debates were largely forgotten. But the combatants didn’t forget. Their deepening hatred for each other is echoed in the widening divide between the two forces in American politics, the right and the left. Buckley died in 2008. His son, Christopher, refused to be interviewed. “This was a festering wound in the Buckley family. I understood why he didn’t want to talk,” Gordon says.

Vidal died in 2012, while the film was in production. “We interviewed Vidal, which we did not use in the film,” Graves says. “He was real cranky, and he didn’t give us any sound bites we could use. But without Bill in the film, it just seemed off-balance.”

Uncivil Discourse

Gordon and Neville’s masterful storytelling help the lessons of Best of Enemies go down easy. “I think the role of the documentary filmmaker is to be a filmmaker,” Neville says. “Remember that movies, whether scripted or unscripted, are about character and story.”

Scenes from the debates alternate with biographical details and contemporary interviews. “We came up with that idea pretty early in the process,” Neville says. “As much as it’s about political debate, it’s also about a championship fight. We knew we had 10 rounds, with a knockdown in the ninth. We wanted that to be the structure of the film.”

But Best of Enemies is about more than a spectacular clash of ideologies and egos. “We wanted to step back and talk about how we argue,” Neville says. “We’re not choosing sides, and not being objective for the sake of being objective. We’re not choosing sides, because we want to make the bigger point.”

That point is simple. “When did civil discourse become uncivil?” Gordon says. “Where are the adults?”

The contrast between Buckley’s and Vidal’s carefully constructed arguments and today’s button-pushing political discourse couldn’t be clearer. “You see a dumb person on television, and you say, ‘They’re dumb like me! That’s cool!'” Meyer says. “I wish people would say, ‘Wow, that dude is so smart. I want to sit and listen to him all day long.'”

Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

Morgan Neville

Neville agrees. “The dumbing down of our media has led to the dumbing down of our politics. That’s something that’s mutually beneficial to the companies who make money off of news and the companies that make money off of politicians.”

The message has resonated with critics and audiences. The film was snapped up by Magnolia Pictures the night of its premiere. “When we sold the film at Sundance, the night we were negotiating with our distributor, Robert said, ‘As long as you open the film in Memphis. That’s a term of selling it to you.’ And they said okay!”

On Friday, August 14th, Best of Enemies goes into wide distribution after earning rave reviews from critics and early Oscar buzz in limited release.

Indie Memphis will host the Memphis premiere on Friday at 7:15 p.m. It will feature a Q&A with Gordon and the sale of Buckley vs. Vidal (The Devault-Graves Agency) by Graves, a transcript of the debates with an introduction by Gordon. There will be another Q&A with Gordon after Saturday’s 7:15 p.m. screening.

Gordon says making the film helped him appreciate how increasing political polarization threatens the very fabric of civil society. “We don’t listen to each other, because we don’t have to. But at some point, we’re going to have to.”

Editor’s note: Our thanks to Malco Theatres for allowing us to use the lobby and projection room of the Ridgeway Cinema Grill for Justin Fox Burks’ photographs.