Bolivar Bulletin, June 26th, 1891: “J.R. Cottingim, of Teague, discovered a negro section hand playing cards last week with his boys, aged twelve and fourteen years. He procured a shotgun and emptied the contents in the breast and shoulder of the negro. The negro is fattening. Cottingim has not been arrested.”

It’s difficult to say which is more appalling — that a man was murdered for such an innocent offense, that the perpetrator went unpunished, or that the local paper printed such a braggadocio account. This story smacks not only of a hate crime, not just part of a conspiracy of suppression, but of complete and utter indifference.

The favored son of a privileged family, enjoying the unlimited excesses of a limited sphere of reality, acting entirely as he pleased, with no regard to the consequences that did not exist.

J.R. Cottingim was a third great-uncle of mine. In surfing online digital newspapers for word of my third great-grandfather, Leonidas Cottingim, I found this quaint tale of my great-great-grandmother’s brother. In light of the recent insanity in South Carolina, I thought I might share some of what family research has revealed about the white-supremacist mindset.

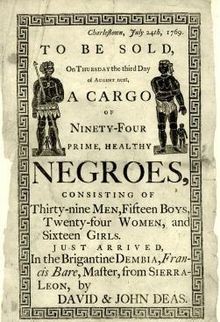

Nineteenth-century America was burdened with a rigid social caste system, which was nothing more than the festering carcass of the centuries-old feudal system imported by our founding fathers. Having roots that run the gamut of said system (Laura Bush is a sixth cousin; my maternal grandfather was a sharecropper’s son) has provided a rare opportunity to study the phenomenon from various perspectives.

The most difficult challenge anyone can face is a challenge to his or her belief system.

A white supremacist was and is nothing more than a person conditioned to that particular mindset, lacking sufficient education or cultural perspective to realize they were spoon-fed an irrational premise. But for as long as they held to this belief, even the lowliest white man could more readily accept his station in life, as long as he had the black man to look down upon — casually overlooking the fact that he could never equal his betters, regardless.

My uncle was conditioned to think of himself as above the law and his victim to think of himself as unworthy. The newspaper editor was conditioned to stoke the flames, and apparently everyone in late-19th-century Hardeman County accepted it all as the normal course of events.

Socially fabricated frailties such as economic division and racial separation, along with the mindset required for their acceptance and perpetuation, are also matters of conditioning. But when an entire social structure buys into a particular way of thinking, who among them has the wherewithal to know any better?

Thankfully, we have finally reached a point in our social evolution where we can break the bonds of ignorance. One more reason to be proud of Memphis is the fact that so far we have avoided the sorts of insanities that have recently troubled other parts of the country.

But if we were to fall prey to such, I would be among the first to show up to defend 21st-century reason against 19th-century delusions — to protect those who only wish to live in peace from those who seek violence for the sake of violence.

So I say to those who still hold to my ancestor’s misguided and antiquated beliefs: It is time to accept that we are evolving away from discernible races. A hundred years from now people won’t even know black, white, yellow, or brown. We’ll all just be a smoother shade of caramel. Along the way, maybe we will achieve a little socioeconomic normalcy while we’re at it. A few may find the transition difficult, but that is one minority we can definitely live without. If you insist on racial purity, I would suggest you go live with the Inuit, although I doubt they would have you.

Education, perspective, and time are the enemies of the irrational mindset. What would be revealed about us by an objective review of what we have been conditioned to accept and perpetuate? What will history say about what we so loosely call society? It’s not about casting stones or lashing out, it’s about finding the strength within ourselves to see beyond. To know for ourselves what is right and to act on those beliefs.

Aaron James, a retired Memphis architect, has spent the past few years researching his family for a soon-to-be-published book titled America: A Family Perspective.