JB

JB

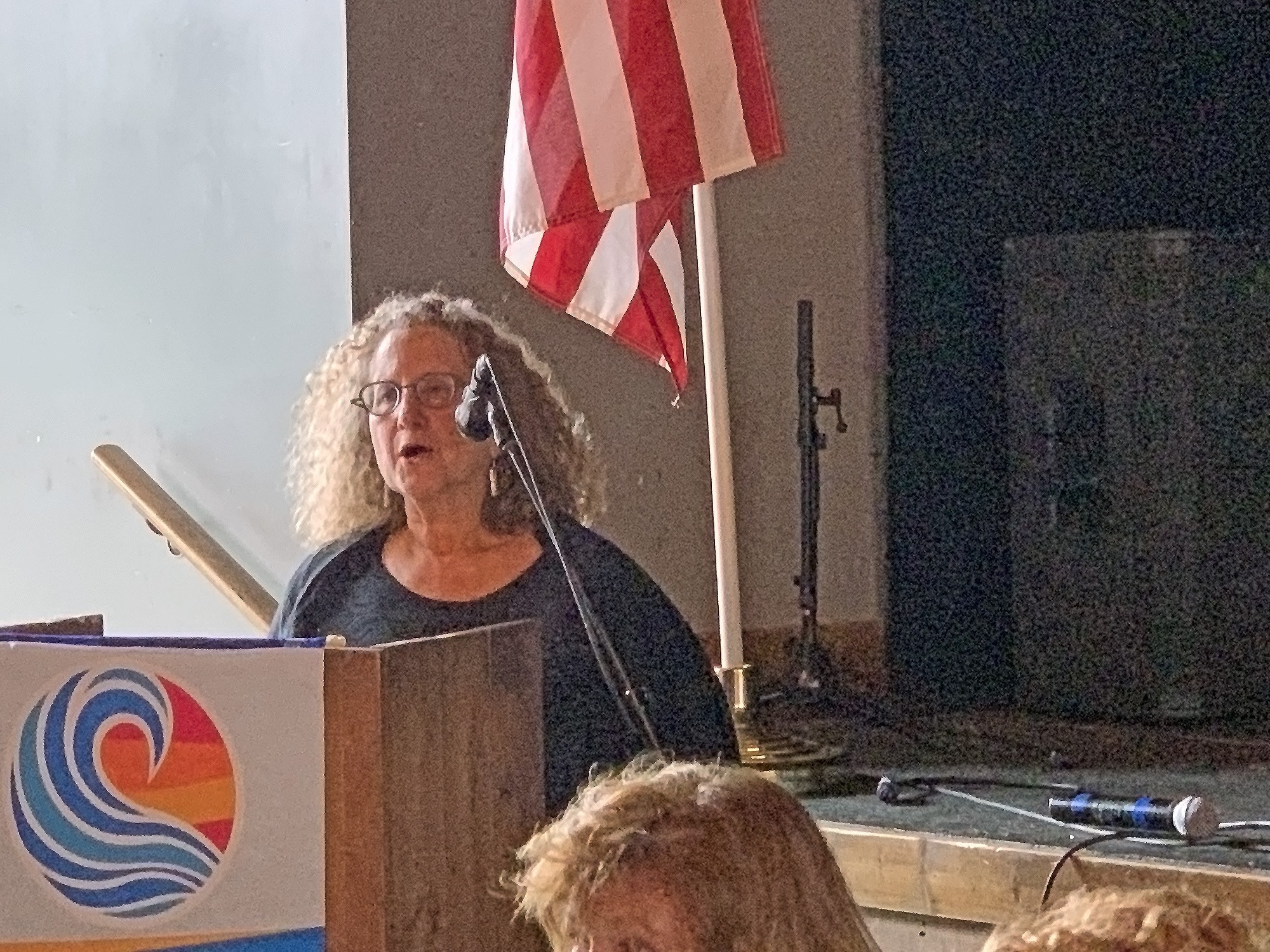

Hedy Weinberg at Rotary Club of Memphis

Hedy Weinberg, executive director of the Tennessee chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, wants it on the record: She is confident that Governor Bill Lee is “very committed to criminal justice reform” and that “we speak the same language” on that issue.

Weinberg made the declaration as part of an ACLU goals review on Tuesday of this week in a luncheon address to the Rotary Club of Memphis. And, after she had concluded her remarks, she submitted to a question-and-answer session and was asked by Rotarian Otis Sanford of The Daily Memphian and the University of Memphis if she was “confident” that Lee “will follow through on this and make a difference with this very ultra-conservative legislature.”

Weinberg answered in the affirmative: “I don’t agree with [him on] everything, but I do have confidence and will be very happy to partner with him.”

In his inauguration address last week, Lee addressed the goal of “safe neighborhoods” and promised to be “tough on crime and smart on crime at the same time.” He elaborated: “[H]ere’s the reality. 95 percent of the people in prison today are coming out. And today in Tennessee, half of them commit crimes again and return to prison within the first three years. We need to help non-violent criminals re-enter society, and not re-enter prison.”

In her remarks to the Rotarians, Weinberg praised Lee as well as the Tennessee County Services Association, the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce,(the Tennessee Association of Goodwills, and the Beacon Center of Tennessee as partners committed to provide progressive remedies to issues of recidivism, non-violent crime, and what she termed Tennessee’s current policies of “over-incarceration.”

The General Assembly has in recent years seen an increasing incidence of cooperation between legislators of the left and right in bills aimed at criminal justice reform. Though she noted remaining islands of obstruction among legislators, Weinberg hailed what she saw as a dawning era of bipartisan agreement on reform issues.

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill