Even if you don’t know what brutalism is, you’ve seen it in action. “Brutalism” is a term given to an architectural style which arose after World War II. Prewar movements such as Art Nouveau and Art Deco had lots of showy bits. Look at the ornate staircase railings in turn-of-the-20th century houses or the intricate glasswork of Tiffany. Art Deco’s architectural masterpiece was the Chrysler Building in New York City, a soaring spire of glass and steel whose crown mimics the rays of the rising sun.

Brutalism shed all of that. For architects like Mies van der Rohe, the beauty of a building lies not in the sculptural ornaments you can make from steel, but from the inherent qualities of the steel itself. The name is derived from a French term for raw concrete. Brutalist buildings often have long expanses of featureless concrete walls. It was somewhat of a utopian project; good architecture could help people live better, cleaner lives. By the late ’60s and ’70s, brutalism came into favor with large institutions like government buildings and college campuses. In Memphis, the Southern College of Optometry’s central tower on Madison Avenue is a prime example of brutalism done well.

But the style has not always aged so gracefully. Many brutalist concrete exteriors got grungy as the years passed. Street artists love to use the blank walls of government buildings as a canvas for graffiti. When the BBC conducted a survey in 2008 to determine the 12 most hated buildings in the UK, eight of them were brutalist. But the style still has many champions, especially in the former Soviet bloc, where brutalism produced many unique works.

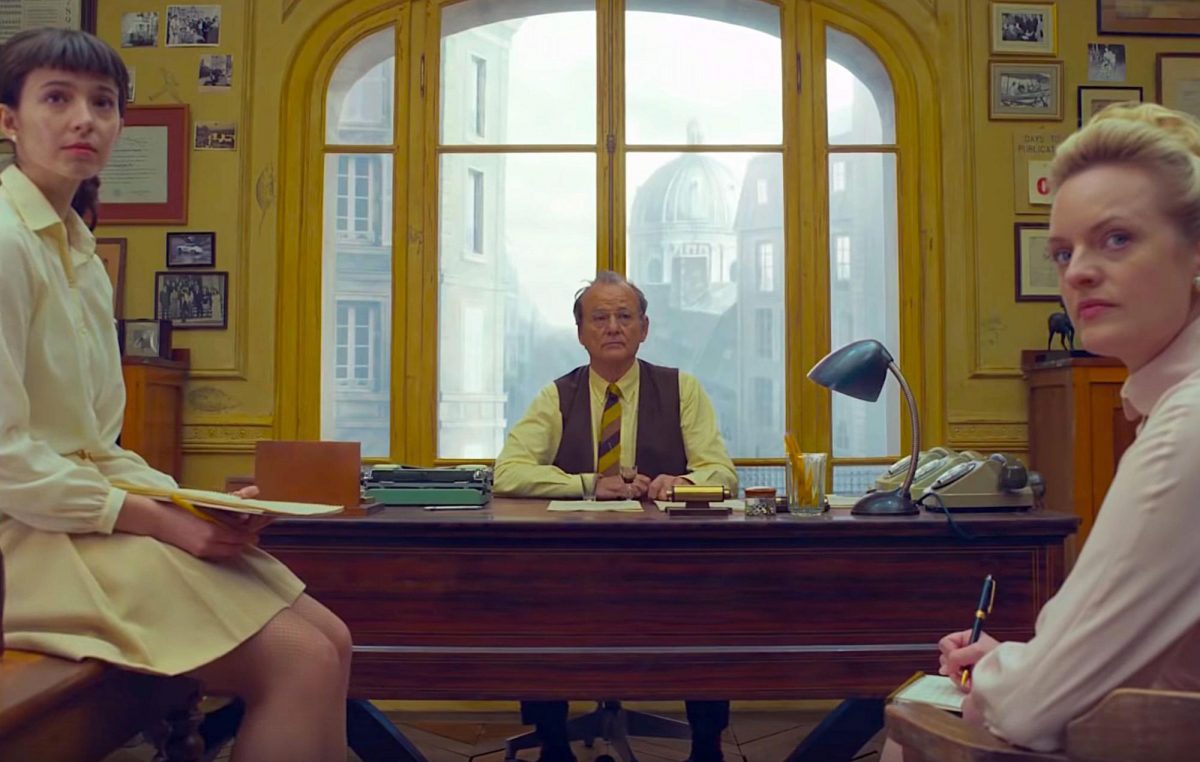

When we first meet László Tóth (Adrien Brody) in The Brutalist, he is on a boat to America. When a cry arises from above, he and the other passengers race up the deck to catch their first glimpse of the Statue of Liberty. Director Brady Corbet and cinematographer Lol Crawley make the visuals match both the ecstasy and disorientation of the moment by following László up the ladder with a handheld camera. When he finally sees Lady Liberty, the camera swoops and rolls, eventually ending upside down, with the torch seemingly hanging from the top of the screen.

Corbet and Crawley shot The Brutalist in VistaVision, a format devised by Paramount Pictures in the 1950s which uses a 35mm negative to produce an image wider than old-fashioned TVs, but not as wide as 70mm widescreen or the 16:9 ratio of most flatscreen TVs. The director said he wanted to shoot this story in a format which matched the time period, and he makes a stirring case for the now-obsolete format. The Brutalist offers striking compositions, which, true to form, highlight the beauty of everyday objects. When László, the impoverished immigrant, takes a job building a loading dock crane, we see it as he sees it — a steel colossus standing against the bright blue firmament.

László makes his way from New York City to Philadelphia, where he is taken in by his cousin Attilla (Alessandro Nivola), who gives him great news. László was separated from his wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones) and orphaned niece Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy) when he was snatched from Budapest by the Nazis and thrown into the Dachau concentration camp. He had given them up for dead, but they are still alive. László longs to bring Erzsébet to America, but she is trapped in Hungary by the Soviet occupation. Plus, László is living in the store room of Attilla’s furniture showroom, so he must improve his station before he can expand his family.

Then, opportunity comes from an unexpected quarter. Attila and László are contacted by Harry Lee Van Buren (Joe Alwyn), who wants them to renovate the library in his father’s mansion as a birthday surprise. During the job interview, László reveals the depth of his vision. He studied at the Bauhaus, an early modernist art and design school in Germany which was declared not Germanic enough when the Nazis took power in 1933. In Europe, he had his own architecture firm and built many buildings, to great renown, before the fascists destroyed the tolerant, liberal society which allowed him to flourish.

The old library is a dusty mess with a cracked Tiffany glass skylight. When László gets done with it, it’s a clean, modernist space with built-in shelving of light wood with massive doors to protect the rare books from sunlight. In the center is a reading chair with a built-in book holder. When the homeowner Harrison (Guy Pearce) returns unexpectedly, he’s furious, partly because he says they have destroyed his room without permission, and partly because he saw a Black man, Gordon (Isaach de Bankolé), on his property. At first, Henry refuses to pay for the work, and Attila blames László’s radical designs. But when a Look magazine journalist profiling Harrison sees the library and gushes about it in print, the wealthy magnate seeks out László to apologize and commissions a great building, which will be László’s American masterpiece. The long road to completing the building, which involves navigating both the conservatism of conventional architecture and the anti-Semitism of the Pennsylvania WASP elite, will consume László’s being.

The Brutalist is a stubbornly old-fashioned film. At 215 minutes, it comes with an intermission, which would have made bloated recent fare like Avengers: Endgame more tolerable. (Lawrence of Arabia, by comparison, is 216 minutes and also had an intermission.) Brody is brilliant as the enigmatic Hungarian, so passionate about his art but chilly even towards his own wife. And why doesn’t Guy Pearce get more work? He’s every bit Brody’s equal as the rich industrialist who uses his talented friend for clout. If The Brutalist stopped after the intermission, it would be a near-perfect film, an immigrant story in the vein of The Godfather Part II. Unfortunately, Corbet can’t quite stick the landing, and it falls apart at the end. But that’s okay. Endings are hard. Architecture is forever.

The Brutalist

Now playing

Multiple locations