With so many Stax-related anniversaries happening lately — including the 20th of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music, officially this May 2nd, and the 60th of the song “Green Onions,” recently celebrated by Booker T. Jones in New York — it’s easy to forget that 50 years ago this February, the main Stax news everyone was talking about was Wattstax, the then-newly released film documenting the previous summer’s festival of the same name.

That moment can be relived visually by anyone lucky enough to dwell in cities with an Alamo Drafthouse Cinema (not including Memphis, alas), with whom Sony has recently partnered in special screenings of the film. But for those who can’t see it, never fear: Stax Records and Craft Recordings have got you covered.

This year the twin labels have released and/or re-released several versions of the live albums that Stax dropped soon after the festival went down on August 20, 1972. The various packages, some documenting the day more completely than ever before, include Soul’d Out: The Complete Wattstax Collection (12-CD & digital), Wattstax: The Complete Concert (6-CD & 10-LP), The Best of Wattstax (1-CD & digital), and 2-LP reissues of the original soundtrack releases Wattstax: The Living Word Volumes 1 & 2.

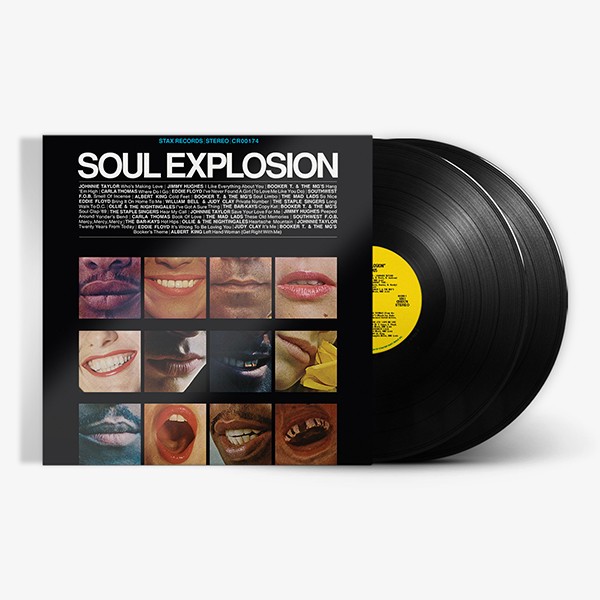

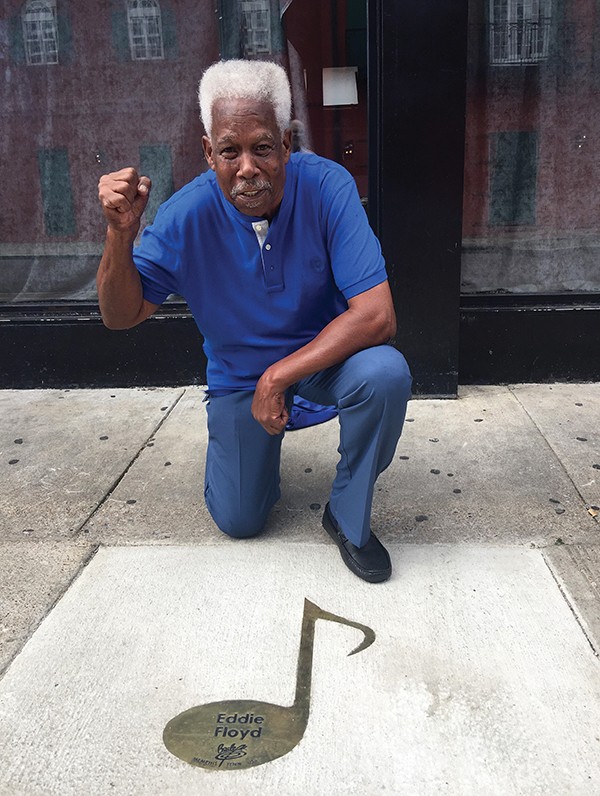

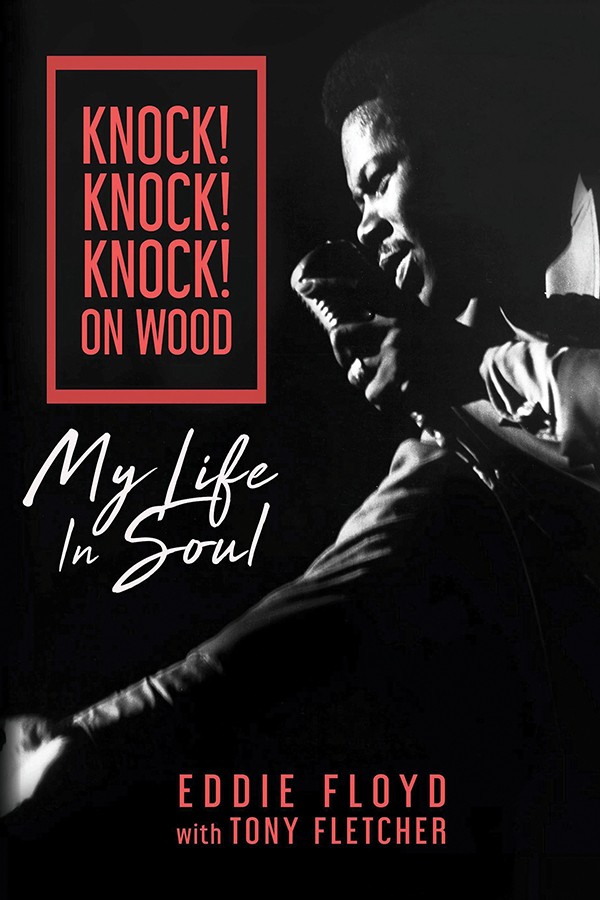

It’s a worthy tribute to a concert considered historic for bringing the likes of Isaac Hayes, The Staple Singers, Rufus Thomas, Johnnie Taylor, Carla Thomas, The Bar-Kays, Kim Weston, Albert King, Eddie Floyd and many more under one billing. It was also a watershed moment in forging a national Black identity, with up to 112,000 (mostly Black) attendees that day. That was about twice the crowd that The Beatles had at Shea Stadium six years earlier, a third of the attendance at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival, and a fourth of Woodstock’s.

So while there was a palpable sense of activism to Wattstax, it was fundamentally celebratory. Al Bell, the festival’s creator and President of Stax Records at the time, called it the “most jubilant celebration of African American music, culture, and values in American history.” And indeed, there’s a mellow yet elated air apparent in the many hours recorded that day at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. That’s in the context of the Watts neighborhood of L.A. enduring crushing poverty, systemic racism, and, in 1965, riots. Bell reflects in the liner notes that “the residents of Watts had lost all hope.” By bringing the best of Southern soul to the neighborhood through Wattstax, at only a dollar a ticket, Bell and Stax aimed to restore hope through Black music (and oratory) that affirmed Black culture and community at every turn.

And oh what music they brought. Among the new Stax/Craft releases, the best way to experience Wattstax as it felt at the time is listening to Soul’d Out: The Complete Wattstax Collection. For lovers of ’70s soul or Stax, it’s hard to imagine a more compelling box set, even if a 12-CD collection can be rather daunting, to mark the transition from classic ’60s soul to the more complex sounds of the ’70s.

The sheer size of the collection helps it capture the luxuriousness of that sprawling day. Now, for the first time, across half of the collection’s discs (also available, without bonus material, as Wattstax: The Complete Concert), is nearly every moment of audio from the show, as recorded by the film crew and later mixed by Terry Manning back in Memphis.

Right out of the gate, we reap the benefits of the set’s completism, as the opening strains of Salvation Symphony by Dale O. Warren, conductor of The Wattstax ’72 Orchestra kick in. Previously available only in an abridged form on the 2003 three-CD release Wattstax, hearing the full 19-minute composition is a revelation. Starting with a martial, neo-classical approach, it reaches a climactic chord (not unlike the final strains of Also Sprach Zarathustra) which abruptly sinks away to make room for an extended soul organ passage, in turn giving way to an extended funk/fusion workout. After that is played out, a new classical movement is taken up. It’s a significant work in its use of multiple genres to mark a new historical moment celebrating the richness and diversity of Black life, very intentionally mastering Western traditions even as it revels in African-derived traditions too. Indeed, the fusion segment relies on an undeniably funky groove that the band falls back on time and again between artists throughout the day. It never gets old.

And there are a lot of artists. Sequenced in the style of a revue, many perform only one song, at least in the early hours of the festival. One standout, also previously unreleased, is an intriguing re-imagining of “The Star Spangled Banner” by Kim Weston and band. While her version of the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” was released in 1973, this take on the more conventional U.S. anthem is just as compelling in terms of artistic ambition.

After these tracks and some introductory comments, the rest of Disc 1 is centered on The Staple Singers, then at the top of their game. Having such bill-toppers kick off the festival is a generous gesture, and quite in keeping with the framing of Wattstax as a kind of gift to the audience. Disc 2 then presents a series of lesser-known Stax artists, dubbed “The Golden 13,” who sing their own hits, then team up to lead the crowd in several choruses of “Old Time Religion,” sounding more New Orleans than Memphis. There’s also a surreal moment when Al Bell receives special honors at an event that he himself planned.

True to the festival’s aesthetic, emcee William Bell reads out an official recognition of Al Bell from the Los Angeles City Council, “now therefore let it be resolved,” etc., to which William Bell adds, “translated it means: Al, you’re outta sight.”

Even more telling is the announcer who appeals to a burgeoning Black nationalism as a way to control the crowd, as he tries repeatedly to clear the stage area of hangers-on. “Folks,” he says, “we have a logistics problem that is really — well anyhow, it’s hard … Now look brothers and sisters, we have to cooperate to make a nation, and a nation doesn’t mean ‘Me, privileged.’ If you’re not working, please have the courtesy to leave the area … Now please, God don’t like ugly!”

It captures the politicized spirit of the event well, and it doesn’t hurt that it’s followed up by one of the most incendiary tracks ever released by Stax, “Lying on the Truth,” by the Rance Allen Group.

More extended sets follow on the remaining CD’s, including those by David Porter, The Bar-Kays, Carla Thomas, Albert King, Rufus Thomas, and, at the climax, Isaac Hayes. Due to technical difficulties experienced by the film crew, Hayes and company play “Theme from Shaft” twice, back to back. (The first version has never been released until now).

Overall, the performances are carried off with precision, passion, and grit, made all the more powerful if one listens across a single afternoon, immersing oneself in festival time. The buildup to Hayes’ set is inexorable, and he and his band are in top form, with the added draw of hearing Hayes take several saxophone solos.

Beyond the festival itself, the Soul’d Out set offering six more discs documenting the Stax-related music featured that September and October in L.A.’s Summit Club. Some of these made their way into the film and the Living Word LPs at the time, but the more complete collection features many never-heard tracks. What’s more, having been recorded in a nightclub, the recordings have the urgency of an interior space filled with people. That quality especially benefits a previously unheard set by Sons of Slum, a hard-hitting Chicago group that unleashes a positively frenetic cover of Otis Redding’s “Respect.”

And there’s comedy, too, with not only the Richard Pryor routines originally featured in the Living Word LPs, but also a comedy set by Rufus Thomas. With these touches, not to mention the Rev. Jesse Jackson’s oration at Wattstax itself, this collection captures a good deal more than music. And the new packaging perfectly matches this time capsule from 1972, including a deluxe LP-sized book of liner notes by Al Bell, A. Scott Galloway, and Rob Bowman.

In sum, it’s an extravagant record of an extraordinary time, and, given the ongoing civil rights battles still being fought today, a history and a spirit worth treasuring in our collective memories.

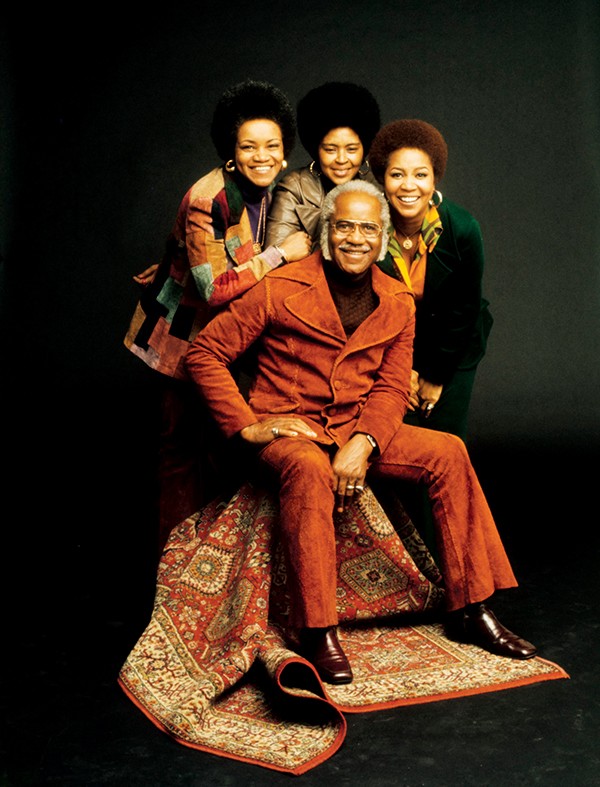

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

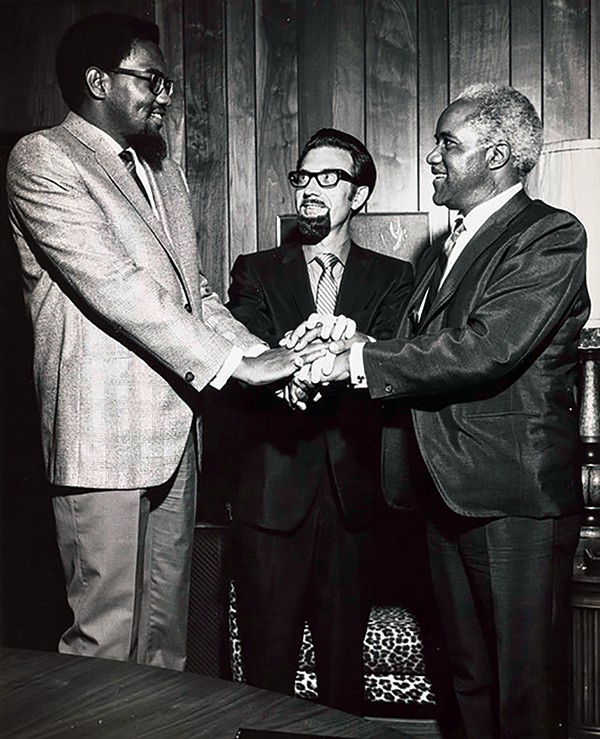

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd  Courtesy of Stax Archives

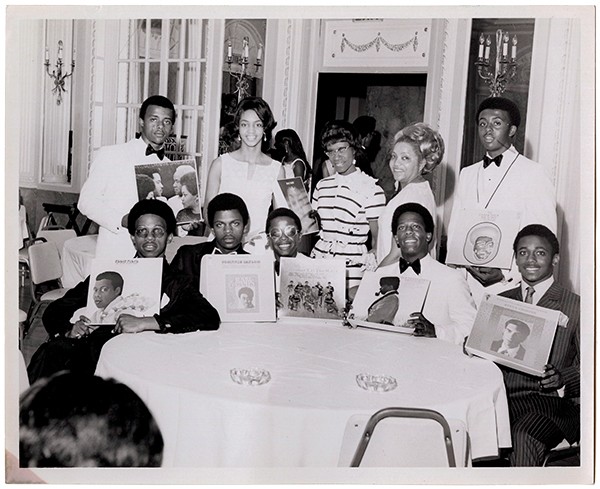

Courtesy of Stax Archives  Courtesy of Stax Archives

Courtesy of Stax Archives  Wayne Moore, photographer; Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Wayne Moore, photographer; Stax Museum of American Soul Music